EDITORIAL: Around the Arctic February 28, 2011 – 3:04 pm

EDITORIAL: Around the Arctic February 28, 2011 – 3:04 pm

Divided they stand

NUNATSIAQ NEWS

Though the Inuit Circumpolar Council billed the event as an exercise in collective unity, the circumpolar Inuit summit held in Ottawa this past week isn’t likely to fool anyone.

On the big question, offshore drilling for oil and gas, individual Inuit within each national region hold a variety of opinions and prejudices, just like citizens of all other advanced industrial societies. So do their elected officials.

This is as it should be, because honest disagreement is a sign of vigour, not weakness. So members of the ICC need not be disappointed that last week’s gathering produced no coherent consensus.

“Right After Sunset, 2009, coloured pencil on paper, by Itee Pootoogook.

“Right After Sunset, 2009, coloured pencil on paper, by Itee Pootoogook.

In mature societies, the manufactured expression of “unity” and “collective vision” are exercises in futility that ought to be regarded with deep suspicion. The notion that any single organization can speak as a single voice for all members of any given group is absurd on its face. Human beings form opinions as individuals, not as members of a collective hive-mind.

Besides, oil and gas drilling in the waters of Baffin Bay off Greenland raises legitimate transboundary issues for Nunavut. In that regard, last week’s summit was a useful exercise.

The ICC fought for years to gain a voice at the Arctic Council and other international forums. Now that they’ve accomplished this, the organization’s members have a legitimate need to air out their conflicting positions to best make use of that hard-won status.

But make no mistake. Greenland, a young, optimistic country now ready to embrace modernity and independence, will drill for crude oil. When they find it, they will produce and sell as much of it as they can, as rapidly as they can.

Kuupik Kleist, the premier of Greenland and the leader of a political party that enjoys strong support among young people, made this clear in a forthright set of statements made to reporters near the start of the summit.

“We are now a full part of the global economy. We cannot hide away or shy away from looking at what’s happening on the rest of the globe,” Kleist said Feb. 23.

That is the voice of confidence, the voice of a country prepared for an independent future built on the extraction of oil and gas. Kleist’s message is that Greenland will do what Greenland must do to achieve this. Though they understand the environmental risks, Greenlanders, he said, are willing to accept those risks in exchange for political independence and economic self-sufficiency.

On the other hand, there are the voices of fear.

Within the three largest entities that comprise the ICC — Canada, Greenland and Alaska — the Nunavut territory likely suffers the most from poverty and underdevelopment.

So it’s ironic that the strongest anti-development voices should emerge from Nunavut, especially in Qikiqtani, perhaps the territory’s poorest region, where at least eight of 13 communities fall into the “have-not” category.

“In Canada, we should not have the position that our social and living [conditions] will change because of oil and gas. It should be in spite of it,” Okalik Eegeesiak, the president of the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, said Feb. 23.

In saying this, Eegeesiak expresses the honestly-held fears of those who elected her: the fear of those who have been sorely wounded by rapid change, the fear of those who long for an Eden that will never return, and the fear of those for whom land, sea and wildlife are to be protected at all cost.

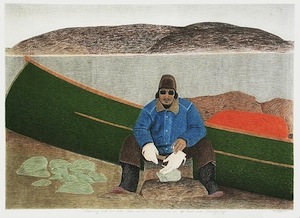

“Carving With an Axe,” 2006, coloured pencil & graphite on paper, by Itee Pootoogook. The inscription reads: “Carving with an axe. Those are the soapstones on the left hand side. Cloudy day.”

“Carving With an Axe,” 2006, coloured pencil & graphite on paper, by Itee Pootoogook. The inscription reads: “Carving with an axe. Those are the soapstones on the left hand side. Cloudy day.”

But Inuit residents of Nunavut and other regions of the Canadian Arctic do not think with one mind on the question of oil and gas extraction and other resource development issues.

The Government of Nunavut, for example, believes the absence of oil and gas exploration in Nunavut waters is rather a big problem. To that end, they sponsored a workshop in Iqaluit this past November to drum up interest in the territory’s undersea oil and gas reserves.

There are many Inuit in the Kivalliq, Kitikmeot and Western Arctic regions who do not fear resource extraction. When he ran for cabinet in 2008, Nunavut’s economic development minister, Peter Taptuna, spoke fondly of the days when he worked with an all-Inuit crew on a Beaufort Sea drilling project in the early 1980s.

Seismic testing? In 2010, a two-day seismic project sent the people of North Baffin into unreasoning fits of rage.

But in and around the Inuvialuit region, eight companies conducted 11,000 kilometres worth of seismic tests using dynamite and airguns, for months on end, in the Beaufort Sea and Mackenzie Delta regions between 2000 and 2003. No one went to court to stop it.

As for mining, most Nunavut Inuit groups have spent most of the past 20 years declaring the territory open for business. Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. even bought into a uranium exploration firm, a move they may one day come to regret. By calling for a review of NTI’s four-year-old support for uranium, Cathy Towtongie, the organization’s president reveals this still remains an unresolved issue in Nunavut.

It’s no surprise, then, that ICC’s resource development summit failed to achieve a strong consensus. On the question of balancing resource development and environmental protection, no such consensus exists. Like every other modern society, Inuit and other Arctic residents must accept the reality of conflicting values.

This means a willingness to listen to the other side, and, whenever possible, a continual search for balanced compromise. Screaming matches and black-and-white thinking will not achieve this. JB