Presented in my professional dossier, August 2024.

Each of us has a unique experience of what it means to be a student. During my youth, my family moved to three different countries, each with a different native language. As a result, I changed schools nine times before university. For me, school was about constant adaptation and catching up. I often felt I did not fit in, and I lost my motivation to learn through these significant and frequent transitions. However, when I enrolled in a school of social work, I began to understand the significance of learning. My teachers helped me recognize that learning was not about achieving grades, getting approval or meeting social expectations. Instead, learning was about understanding how the world functioned, my role within it, and how I could contribute as a social worker (SW). This provided me with a natural motivation, curiosity and desire to learn. As I enter the classroom as a teacher, I am always looking for this genuine curiosity in students and trying to bring it into our learning experience.

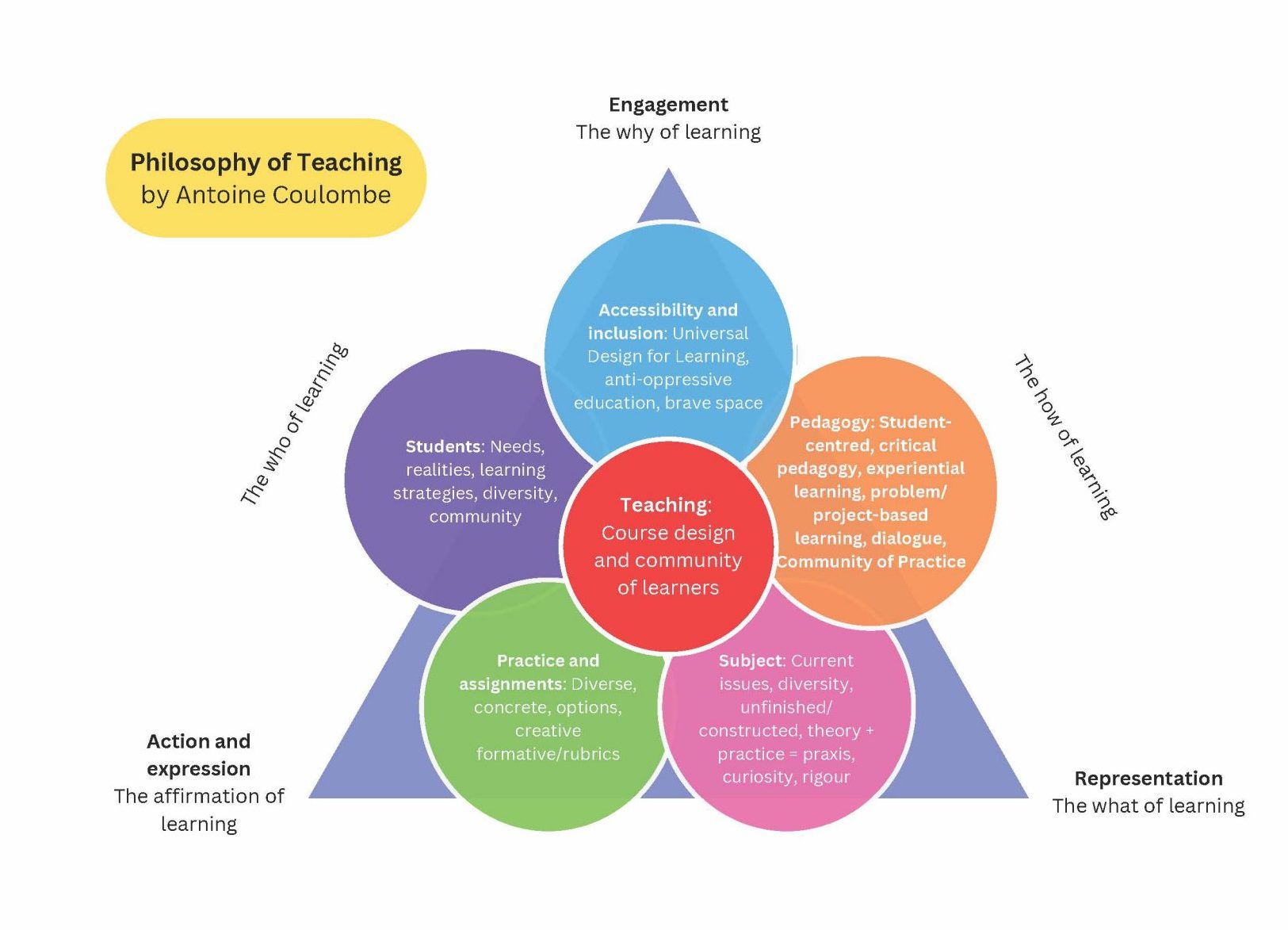

The learning process is complex and follows three fundamental principles: engagement, representation and action (Bracken and Novak, 2019). First, individuals must be engaged and motivated to learn. Once engaged, they need access to knowledge and materials to be learned and developed. Finally, learning is only complete when demonstrated; learners need opportunities to practice, express and show their learning and apply it to real-world situations to better the individual, the community and society. My teaching philosophy enacts these three principles through course design that integrates five key elements: an understanding of students’ diversity, design that promotes accessibility and inclusion, student-centred pedagogies, relevant subjects and topics, and the thoughtful inclusion of opportunities for students to practice and demonstrate their learning.

Understanding Student Diversity, Promoting Accessibility and Inclusion

The first step to building engagement in learning is understanding a classroom’s diversity and the students’ uniqueness, learning strategies, needs and barriers (Fry et al., 2003). Higher education can be a complex environment for people with disabilities, equity-deserving groups, people in poverty and anyone who did not grow up in a family with a higher education background (Strange and Cox, 2016). These populations experience a disproportionate number of barriers to learning, which impact their ability to engage and succeed. I build student engagement and participation in learning by reducing the obstacles that students experience and increasing the accessibility of my courses. To promote equity and inclusion, I continually reflect on my teaching practice, as “anti-oppressive teaching happens only when we are trying to address the partial nature of our own teaching” (Kumashiro, 2004). I also invite students to reflect critically on their own classroom experience, relationships with colleagues, the subjects being taught and their own learning experiences.

When discussing safety in the classroom, I acknowledge the risks and challenges of engaging in a learning community and work collaboratively with students to increase safety and create a brave space (Simon et al., 2022). To help my students sustain and self-regulate their engagement with the learning process, I adopt accessible learning tools and identify teaching strategies that can effectively stimulate their interest.

Student-Centred Pedagogies

My teaching pedagogies focus on student-centred (Hoidn and Klemenčič, 2020), critical (Freire, 1998) and experiential learning (Kolb, 2005). They de-emphasize teachers as experts and re-centre students as active participants in a community of learners. Learning together changes the paradigm that teaching must be done by an expert and empowers students to be responsible for their learning and to make sense of knowledge. As Freire reminds us, “to teach is not to transfer knowledge but to create the possibilities for the production or construction of knowledge” (1998). My role as an educator is to provide a supportive and conducive student-centred learning environment that encourages critical thinking, shared power, dialogue and action, in which students can work individually and collectively to assimilate and analyze information and turn it into knowledge. In doing this, I help SW students to deepen their ability to understand the complexity of SW, use theory to engage meaningfully in their practice and become critical thinkers.

Relevant Subjects

For teaching and learning to be meaningful, they need to be connected with concrete situations and history. When we learn about how the world functions, we can participate in it and change it for the better. The classroom becomes a space where we can be part of history as it is being written (Freire, 1998). SW is a continually evolving field, and I renew my understanding of it in an ongoing way by positioning myself as a learner with my students as we explore topics in SW. Together, we co-create knowledge by continually creating, re-creating and adapting our understanding of SW.

I bring a unique francophone and Quebec perspective to teaching social work. In Quebec, social workers and community organizers have played a pivotal role in improving the socio-economic conditions of the francophone majority by combatting oppressive religious, economic and institutional systems that marginalized them. When I teach, I draw from my education and practice in Quebec to demonstrate how social work and community organizing can promote citizenship, autonomy, and social change.

Opportunities for Practice

Assessments play an essential part in students’ learning, as they “define what students regard as important, how they spend their time and how they come to see themselves as students and then as graduates” (Brown et al., 2013). To help students prepare for the complexity of SW practices, I create assignments that are practical and address real-life situations. These assignments require self-reflective, active and problem-based approaches. For example, in a community organizing course I teach, students plan and complete real projects that make an impact in the community. In a social analysis course, students analyze the oppression and discrimination that service users experience, as the students saw in their practicums. Assignments like these promote deeper learning and give students opportunities to demonstrate their abilities to understand, apply, analyze, evaluate and create (in keeping with Bloom’s taxonomy of learning; see Krathwohl, 2002). In this way, learners demonstrate their learning by using it in real-world situations. Doing this helps students to engage, knowing that they are learning to solve real-world problems through their assignments on their way to becoming SW.

Course Design

Robust course design is a way for me to embrace the complexity of teaching and ensure that I implement the principles and key elements described thus far in the courses I teach. I select the appropriate learning objectives, content, pedagogy and assessments through course preparation to enhance the student learning experience (Fry et al., 2003). My preparation acknowledges that why and how we learn are just as important as what we learn. I encourage student engagement in learning by connecting the classroom and the community of learners with relevant, real-world problems and providing the opportunity for them to demonstrate and apply their knowledge to problem-solve. Good course design simplifies learning by helping students understand the course, navigate the semester-long learning arc, and become more independent in their learning journey. A healthy course design ensures that the three essential principles and five key elements of learning are present in my work so that once the course begins, I can focus on the teaching and the learning experience.

Looking back at my personal experience, my SW teachers helped me heal as a learner, become a complete person and find my place as a SW in the world. I understand from this experience that teaching is “about healing and wholeness. It is about empowerment, liberation, transcendence, about renewing the vitality of life. It is about finding and claiming ourselves and our place in the world” (Palmer, 2012). My journey as an educator is now dedicated to creating a space where students can engage in their journey to becoming whole and, together, find meaning in being a SW in this world. Each time I enter the classroom, I am reminded of how privileged I am to be an educator.

Brown, G. A., Bull, J., & Pendlebury, M. (2013). Assessing student learning in higher education. Taylor and Francis: city.

- Freire, Paolo, (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Fry, H., Ketteridge, S., & Marshall, S. 2003. A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education: Enhancing academic practice (2nd ed.). Kogan Page.

- Hoidn, S., & Klemenčič, M. (2020). The Routledge international handbook of student-centered learning and teaching in higher education. Taylor and Francis.

- Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4, 193–212.

- Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(4), 212-218.

- Kumashiro, K. K., Taylor & Francis. (2004). Against common sense: Teaching and learning toward social justice. Routledge Falmer.

- Palmer, P. J., (2012). The courage to teach: Exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life (10th anniversary ed.). Jossey-Bass.

- Simon, J. D., Boyd, R., & Subica, A. M. (2022;2021). Refocusing intersectionality in social work education: Creating a brave space to discuss oppression and privilege. Journal of Social Work Education, 58(1), 34-45.

- Strange C. C., Cox D. H.(Eds.) (2016). Serving diverse students in canadian higher education. McGill-Queen’s University Press.