Hey, thank you for joining me for my first ever blog post!

I am so excited to get writing and keep you up to date in all that is happening in my life, and hopefully show you a bit of how I see the world. Your feedback is always appreciated and I look forward to this journey.

As you may well know we are in the midst of some of the most transformative times in recent human history. I suppose change is to be expected, after all it is one of the few inevitabilities in life. Unfortunately, as you may have noticed, inevitability does not always produce a situation that is any more palatable. In this case, we are forced to do the unthinkable: suppress the natural and human urge to be social and connect with each other.

As someone who studies the environment, I am constantly reminded of a connection that many have recently been reacquainted with, this being our connection with the land. COVID-19, and the Social Distancing that accompanies it, presents an excellent opportunity to reconnect with the natural world. For those of us lucky enough to have a patch of soil to cultivate or access to a public path on which to recreate, the realisation of our need for a connection with nature has been undoubtedly strengthened in recent weeks.

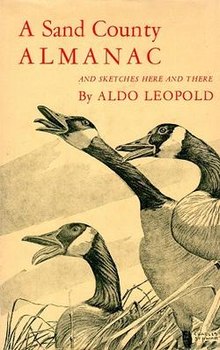

Throughout my degree, I have heard rave reviews of two cornerstone books in Environmental Literature, these being “A Sand County Almanac: and Sketches Here and There” by Aldo Leopold and “Silent Spring” by Rachel Carson. Between gardening and online classes on Greek Mythology, I have decided to delve into these two pieces and see what all the hype is about (beginning with the prior).

Leopold’s work chronicles his life in Sauk County, Wisconsin. He does so with ardent precision, personifying nature in such a way that captures its inherent beauty and fragility. Few writers can capture the natural world in such a way and I can see why it has resonated with so many environmentalists.

Quite early in the book, one quotation stood out to me:

“There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm. One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery, and the other that heat comes from the furnace .” (27)

Upon reading this I was smitten with a realization of the amount that modern life is simply taken “as is”. Rarely do we reflect on the immense difficulty required to produce the beet on our plate or heat in our stove. When Leopold speaks of the life of the oak tree he later burns, we are forced to ponder our relationship with our own consumption:

“We sensed that these two piles of sawdust were something more than wood: that they were the integrated transect of a century; that our saw was biting its way, stroke by stroke, decade by decade, into the chronology of a lifetime, written in concentric annual rings of good oak.” (33)

In many ways, the way we as westerners currently interact with the world is designed to allow us to forget the life cycles of the objects around us. For lack of a better comparison, we have “Marie Kondo-ed” our consumption. Despite this, I am beginning to think that what ‘doesn’t bring us joy’ may, in fact, bring us a heightened sense of stewardship and humanity.

This acknowledgement of separation from the land is mirrored in William Cronan’s essay “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature” (A work I would strongly recommend reading if you have the time). In both settings, we see an abject disconnect from acknowledging our position in ecosystems.

This brings to mind the implications in the planning of cities and urban settings. To see a change in collective attitudes towards the environment, we must begin to reincorporate ourselves into the natural world ( Both in the mental and physical realms).

Urban forests and farms, two industries which are seen as largely rural, have as of late become more of a talking point in the discourse surrounding our built environment. I long for the day that every front lawn has a garden, and the origins of our food are understood by all. Alas, this may be a lofty dream, but I hope that this time we have spent in isolation will help advance the progress already made to develop robust, and environmentally engrained urban environments.

*2020-05-25 Edited for Grammatical Fixes*