2:6 –Response to Question 1

Read “Coyote Makes a Deal with King of England”, in Living by Stories. Read it silently, read it out loud, read it to a friend, and have a friend read it to you. See if you can discover how this oral syntax works to shape meaning for the story by shaping your reading and listening of the story. Write a blog about this reading/listening experience that provides references to the story.

“Coyote”

As King suggests in his article “Godzilla vs. The Post-colonial,” Robinson’s “Coyote Makes a Deal with King of England” is written using syntax that defies silence. In fact, with its repetition, plot diversions and syntax, its almost impossible to understand if you read it to yourself. But read this story aloud, ideally to another person, and your voice naturally pauses in the appropriate places, you begin gesturing with your hands in others, such as the suggestion that the “black and white” law book is “about this long and about this wide” (84).

Repetition is an important characteristic of this story, and one I noticed right away. The word “fire” is repeated four times on the first page of the story. The specific phrase “they got a fire” is repeated twice on the first page. This becomes a trend throughout the story, and I noticed that this use of repetition helps not only with the flow of the story, but the rhythm.

This article speaks about the importance of rhythm in children’s stories. Children’s stories are one of the few structured oral storytelling methods surviving in Western culture. The distance between beats and the number of beats are cited as two important characteristics of good rhythm in a story. Robinson’s has both. The words used for the story are similar in length, and visually, the text is structured like a poem in that it has stanzas of text rather than traditional paragraphs.

Plot diversions are another aspect of this story that, unless read allowed, trip up the reader. The narrator seems to be talking to the audience directly in many of these plot sidelines, or arguing with himself. One instance is on page 81, beginning at the first line of the page from “That’s all the name I know” to “Only name I know, that was TOH-mah” (81). Here the narrator has stopped the story to try to recall a character’s name, but can’t seem to precisely remember it. The narrator struggles aloud for several lines before giving up and moving on. This is really hard to follow when reading silently, but when read out loud, it flows better. The speaker can use tone to make it clear that the narrator is thinking to themselves rather than speaking to the audience.

The syntax itself contributes heavily to the rhythm, as I mentioned, and this is due I think in a majority to word length and use of contractions. The language is very informal, words such as “writing” or “until” replaced with “writin'” and “’till” (79). Repetition is used here as filler. Where some people might use “like” or “um” when speaking naturally, the narrator recreates these breaks in speech by repeating themselves, such as on page 66: “Do you know what the Angel was?/Do you know?/The Angel, God’s Angel, you know.” This is an example of filler speech because it does nothing to move the story forward, it is simply stagnant.

Robinson is able to write a story and make it seem like he is simply transcribing a story he is hearing. The experience is one of both listening and reading, but much of the story is lost or cannot be properly understood without listening to it read aloud. This was an interesting experience for me, especially once I realized I could connect this experience with folk tales and other stories I was read to as a child, meeting four of the five points of a children’s story that I remember being significant to a good story.

Works Cited

Coyote. Digital image. Wikipedia. Wikipedia, 29 June 2016. Web. 29 June 2016. <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coyote>.

Heathfield, David. “Rhythm, Rhyme, Repetition, Reasoning and Response in Oral Storytelling.” TeachingEnglish. British Council, n.d. Web. 30 June 2016.

King, Thomas. “Godzilla vs. Post-Colonial.” Unhomely States: Theorizing English-Canadian Postcolonialism. Mississauga, ON: Broadview, 2004. 183- 190.

Robinson, Harry. “Coyote Makes a Deal with the King Of England.” Living by Stories: a Journey of Landscape and Memory. Ed. Wendy Wickwire. Vancouver: Talonbooks, 2005. 64-85.

Shepard, Aaron. “Rhythm and the Read-Aloud.” (Writing Books, Stories for Children). Aaron Shep, May 1999. Web. 30 June 2016.

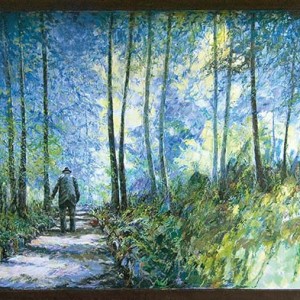

The image to the left is the mural in my town called “The Hermit,” and it was true that not many referred to Charlie by name then, or now. When I was younger, I liked this mural most for the feelings of peace and serenity every time I looked at it…and also for the powerful story behind it.

The image to the left is the mural in my town called “The Hermit,” and it was true that not many referred to Charlie by name then, or now. When I was younger, I liked this mural most for the feelings of peace and serenity every time I looked at it…and also for the powerful story behind it.