Home is so many different things to me. While thinking about home this week, I keep coming back to a handful of images and feelings: to the rooms; to the walls and to the people in them; to feeling welcome; to being unwelcome; to squares of land assigned ownership; to considering what it means to be looking for a home here; and to wondering if a home in myself is a home enough.

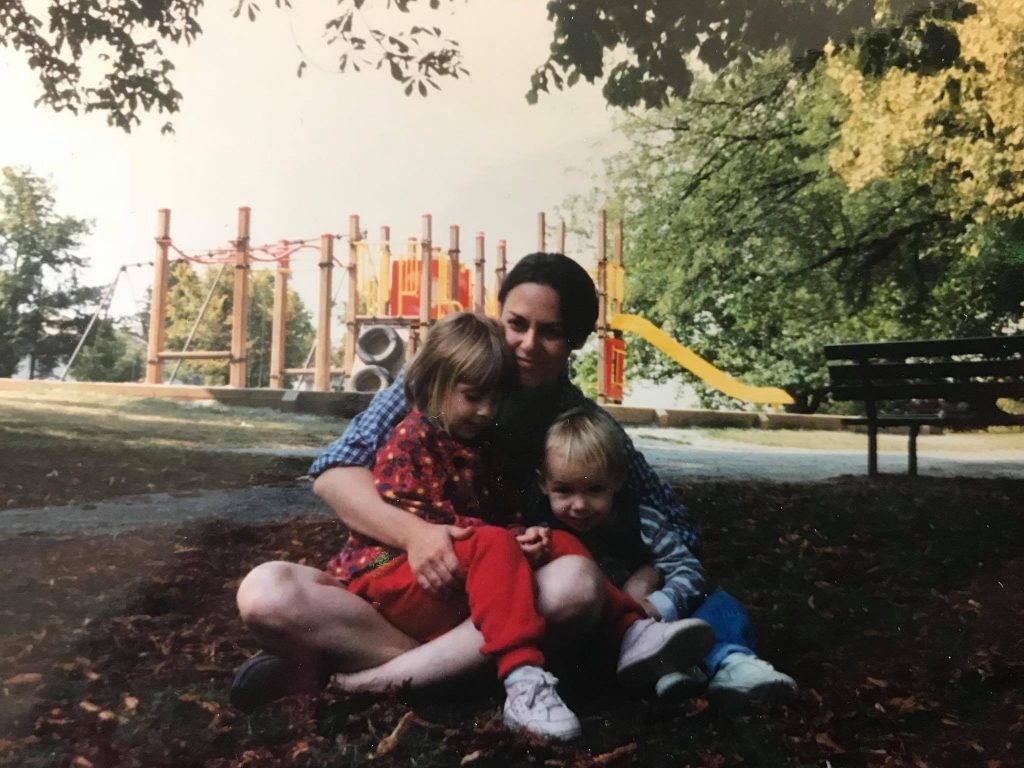

In my early childhood my home was in a complex here in East Vancouver, there were other kids my age there and we would spend day after day playing in the courtyard, finding bugs and playing tag. Me and my younger brother shared a room with glow-in-the-dark stars on the ceiling. Our mother put everything she had into making that space a happy one for me and my brother, even when we were broke, she never let us feel it. This place had always felt like home to me back then, like no other place has since.

Eventually my father won custody of me and my brother because he had a steady job and my mother didn’t. Today I know how lucky we were to have two parents who both wanted us, but even now I often look back at this part of my life with a lot of pain. We moved to Winnipeg to live with him, and I began my own journey with anxiety and depression which went undiagnosed. I remember I used to have nightly terrors, dreams that told me to fear the walls around me, that I was trapped. Ten year old me thought I was somehow very broken, but looking back now I think I was not so broken, but I simply missed my old home and my mother.

We would leave that house soon and hop around Winnipeg for a number of years, eventually staying for 8 or 9 years in a little green house on Garwood street. My feelings about this space are so mixed. It was sometimes beautiful and other times abusive. Some mornings I wanted to lay in my bed forever, and some nights I wanted to leave for good. Oh, the teenage runaway, it sounds like 100 cliche movies, but I know that so many of us do share these stories. My father often told us that we should leave and “see what it’s really like out there on your own”. He never meant it, just wanted to scare us straight. But almost inevitably, first my brother and then me, we each ended one of our fights with our father in a decision to leave home for good.

Since then I’ve never lived in one place for more than a year, and I’ve never felt attached to a space like I did as a child. Today this makes me realize how much the feeling of belonging somewhere was dependent on having people there who I loved.

Moving back to Vancouver as an adult brought me a boat-load of confusing feelings. The ocean and the rain and the trees and the grass were all shouting at me “remember us!”. More than anything, they reminded me of my mother and our time together here. I saw her and my childhood on every street corner that I recognized, at the parks she brought us to, even in the produce markets and how blackberry bushes grow in the alleyways.

However, staying here, and growing here, made me realize that this place was no longer my home, and that truthfully it never had been. While things were all so familiar, they were also all so different. And more so than before, I was here alone. Without my mother in this space it could never feel the same, she had moved long ago to follow us even while we couldn’t live with her.

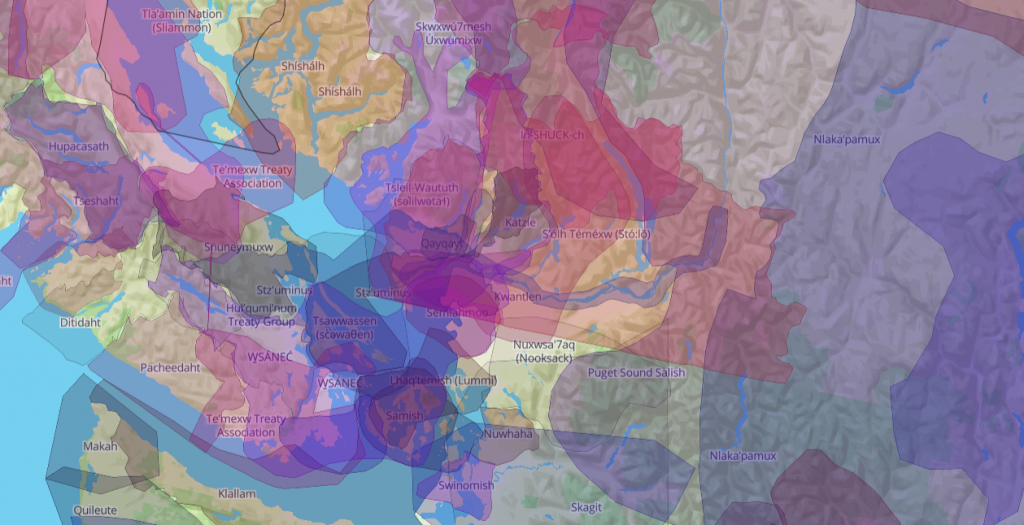

On top of that, while our place in east van had been a home, it had never really been our home. It never really belonged to us, as none of my other homes had. They were built on squares of stolen Indigenous land commoditized by settlers. They were all places we should never have been in the first place. Sitting in the park against the trees, fingers in the moss and head turned to the sky, this land that I loved was land that I wronged everyday as a consumer, as a settler, as someone working in a capitalist system in a colonial state, as a girl who wanted so badly to belong, but knew she could never count the number of girls who lost their own homes in these same places.

Today I live in a studio with my cat Sally. My relationship to this land continues to be complex and full of problems. I do find some hope for resolution in my desire to make this place a little better, to push towards decolonization, and to show love to the people I encounter. While I still long for the feeling of family and belonging in a space, I’ve been working to find that home of love and acceptance within myself.

In reading this over I realize that I’ve been very vulnerable with you all tonight. It was really important for me to share my emotional truth on this topic of home, so thank you for listening <3