Wading into the depths of practicum, I am challenged to find ways to integrate my inquiry with my practice. This has taken shape in trying to integrate students’ mother tongues into the classroom, as mandated by the International Baccalaureate Primary Years Program (IB-PYP). As my teaching load increases, my perspective on this issue is starting to change.

In a meeting of all the PYP teachers at the school, it came to light that in a recent accreditation evaluation by the International Baccalaureate Organization, the school had received several recommendations to improve the integration of mother tongue into classrooms. Interestingly, some of these recommendations were repeated from a similar evaluation done six years ago. My initial thought was: is it really so hard to bring students’ other languages into a school? I believe that one might argue both yes and no.

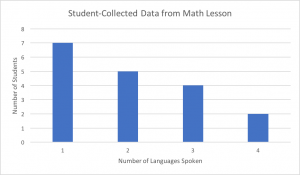

Although I knew that my class was both culturally and linguistically diverse, I wasn’t exactly sure to what extent before starting my long practicum. The results (see below) were impressive. More than half of the class reported that they speak at least one other language in a data-collecting exercise.

Encouraged by this, I triumphantly began to plan some class activities that would take advantage of this rich linguistic resource that the students brought to school. I had the support of my school advisor, who added that she wanted to see more integration of mother tongue in the school, with the specific example of the upcoming PYP Exhibition, in which she would like to see students be able to present their projects to their families in their mother tongues.

I then began to include a few simple language activities in the mornings. The first was a raffle where students were asked to write the name of a fruit in another language and enter it into a draw. I would then choose one word every week to be the ‘magic word’ that I would use when giving instructions. Those students who did not speak another language were encouraged to look one up, use a word from French class, or ask a classmate. The ensuing discussion and engagement in the activity was surprising; some students showed obvious pride and enthusiasm when talking about their language or dialect and were eager to share. Another morning, students were asked to do a math problem in another language, with similar results. In this small way, other languages are making their way into the classroom, and hopefully these small steps can lay the groundwork for more significant integration in the future.

As I move into taking on more of a lead role in the classroom, the reasons why mother tongue integration might be overlooked start to become obvious. A teacher has fifty other equally-important considerations to be conscious of on a daily basis, be it Social and Emotional Learning, making a classroom Gender-Inclusive, or integrating First Peoples’ Principles of Learning. It is completely understandable that the inclusion of mother tongues might be eclipsed by these. I hope to be able to make students’ other languages a daily part of the classroom, and accept that it may not be as easy as I had initially thought.