Ever find yourself beet red after one small drink? You’re not alone! Over one-third of East Asians and eight percent of the world population experience this awkward phenomenon; however, a solution is in the works. Just last month, researchers from Weill Cornell Medical College have solved this problem by experimenting with targeted gene therapy on mice.

What does asian glow look like? A before and after comparison. (Credits: Wikimedia Commons)

The Dangers of Asian Glow

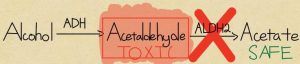

Apart from causing embarrassment, asian glow comes with more serious consequences than just flushing red. The red glow is caused by a deficiency in the ALDH2 enzyme, a key component in detoxifying alcohol. When you drink alcohol, your body converts the alcohol into acetaldehyde. Normally, acetaldehyde is further converted to a safer compound by ALDH2; however in individuals with asian glow, ALDH2 does not function, causing acetaldehyde to build up. Since acetaldehyde is a cancer-causing agent, its accumulation drastically increases the risk of developing esophageal cancer by six to ten folds.

Conversion of alcohol to acetate is stopped in people with asian glow. This leads to toxic buildup of acetaldehyde. (Credits: Me – created with Notability)

A Glowing Solution…

Matsumura’s team reasoned if a lack of ALDH2 enzyme was the problem, maybe they could simply add it back in.

“We hypothesized that a one-time administration of a […] virus […] expressing the human ALDH2 coding sequence […] would correct the deficiency”

They tested their idea on three strains of mice: mice with functional ALDH2, mice lacking ALDH2, and mice with a non-functional version of ALDH2. The latter two simulated the asian flush syndrome seen in humans. After introducing all the mice with the ALDH2 gene and feeding them alcohol, the researchers carefully monitored acetaldehyde levels in the blood.

Their hard-work paid off! In the two strains deficient for ALDH2 function, acetaldehyde levels and abnormal behavior associated with alcohol consumption were back to near-normal levels. Furthermore, they found that one dose was enough to confer persistent and long-term protection.

From Mice to Humans: A Complicated Decision

Matsumura’s team emphasize that a long-lasting treatment for ALDH2 deficiency currently does not exist. Although making the jump from mice to humans will be challenging, they assure that virus-mediated gene therapy shows the most promise in becoming an effective therapy. The million-dollar question is whether the risks of the glow outweigh the benefits of reduced alcohol consumption seen in affected individuals. To this Matsumura’s team say:

“the overall burden […] on human health, particularly […] cancer, supports […] gene therapy.”

What do you think?