I still remember when my parents and I immigrated to Canada; I was six years old. On my first day at the new school, I fell asleep during class because I was accustomed to the designated nap-time back in Nanjing. The teacher had to wake me up, then asked if I was okay, and laughed along with my classmates. Needless to say, it was embarrassing and difficult to merely adjust my nap schedule.

There were the multitudinous instances of deviation from the old world I had known and the new world I was thrust into, language barriers aside. My lunches were too strange, too smelly, and too inedible to the other kids, and I was ashamed of the sustenance that my mother or grandmother provided me. Food had never been so difficult to consume until I experienced my own deviance, through other people’s eyes, and this worried me from Grade One until Grade Six. Not only did food mark me as “different”, I was also “wrong”. I thought maybe it was inconsiderate of me to eat rice and fish with the little bones to be picked out by every bite, or it was bad to unveil damp dumplings that smelled of pork and sour vegetables even when eaten cold. I thought that perhaps my sense of taste and smell were skewed or completely opposite from my peers’ in this world.

Fred Wah writes in Diamond Grill how his mother “knows the girls don’t like garlic breath on her boys” (47), echoing my own anxieties, but when confronted by his then-girlfriend’s complaints of his breath, Fred tells her “she’s nuts, I can’t smell a thing and all she has to do is eat some garlic each night for supper and everything’ll be cool” (47). But even Fred can’t handle the “pungent chunks of ginger” (44) in Chinese dishes, and picks them out before eating, much to his father’s chagrin and disappointment that Fred Jr. is not “Chinese” enough.

I also remember when my school-friend’s stepfather scolded me with disgust on his tongue, upon picking her up from my house and meeting me for the first time, for not being “very Chinese” (he is Caucasian, I must note here, but his wife and stepdaughter are both fully Chinese; I could, and still can, see just how narrow his definition of what being “Chinese” or, more specifically, being “a Chinese girl” is — to be submissive, quiet, docile, eager to please), encouraging such stereotypes that are ingrained in North American schema and are altogether troubling, regressive, and, simply, racist.

And even though my appearance may suggest that I have lost touch with my cultural roots, and though I seem to have assimilated into popular North American culture, and though I may not be submissive nor quiet nor docile… my taste in food gives away my thick Canadian disguise, shucks off my acculturated mask, and lets me enjoy the one connection I have to my long-lost culture: my grandmother’s cooking.

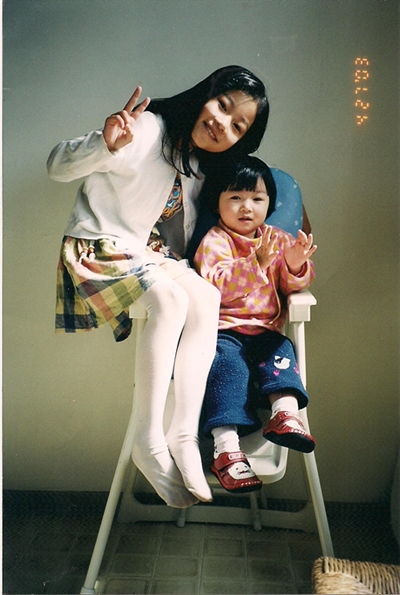

My grandparents speak no more than six words in English, and I speak fragmented Mandarin, so sometimes I am sad thinking that I may never learn the recipes and my heritage will end with my younger sister (born in Vancouver one year after we immigrated here, and still cries about being Chinese on the outside and Canadian on the inside) and me. But sometimes I think I can still learn. Like Fred Wah, when I indulge in the foods that are foreign and/or unpalatable to most of you (dishes without names because I only remember their tastes, smells, and manifestations; dishes that have been around since I was born, since my mother was born, since my grandmother was born), I am indulging in my rich history, my family’s life narrative.

I have somewhat similar experiences with you, having come to Canada in elementary school as well. I really understand the whole lunch issue because I brought sandwiches to school most of the time precisely to save myself from the experiences you shared, although, of course now in hindsight, I have a totally different understanding of my surroundings. I found your blog to be empowering, not because it protrudes a political or social declaration, but because it captures the mindset of Asian Canadians who have reflected and formulated attitudes on how to deal with cultural identities. “[T]hough I may not be submissive nor quiet nor docile… my taste in food gives away my thick Canadian disguise,” really hit the spot for me because it shows that you are in touch with the Chinese culture in a way that predispositions and expectations of a cultural framework does not interfere in formulating who you are as a person.

The stereotypes propagated by White colonialists are nonetheless major issues. As an Asian male living in North America, I cannot aptly express in words the disdain I have for the mainstream media that attempts to emasculate and undermine non-white men on TV, and I cannot say that I am oblivious to the sentiments ingrained in the culture. But I also know something else, that I don’t have to prove my “Canadianess” or “Koreaness” to anyone.

While reading many of the blog posts and hearing about my peers’ experiences trying to steer their way through their ethnic identities, I initially found myself wanting to be able to relate, but not being able to. I am white and my parents and I grew up in Canada (my grandparents came to Canada when they were very young from the Ukraine). While my last name is now Bachynski, I grew up with the last name Andrews- pretty much as generic North American of a last name as it gets. My grandfather escaped the war, and when he arrived back in Canada, he wanted to have a very “Canadian” last name in order to cover up his return. Hearing your story about the Caucasian man rating how Chinese he thought you were, really made me question how we pick and choose when it is ok to adopt or refrain from your cultural heritage. I have never had any expectations placed on me to fulfill the role of a Ukrainian person. I have never had to check off Ukrainian on a form, or call myself Ukrainian-Canadian. While there are many cultural Ukrainian traditions that I participate in, my heritage does not come up very often in my everyday life. A couple months ago I was having a chat with a stranger who asked me “what are you?” as in, what is your ethnic background? When I told him I was Ukrainian, he asked me if I spoke the language, or had ever visited the country. When I said no, he thought it was sad. I immediately felt that he was right, I had never really made the effort to fully immerse myself in my family history in the way I would like. While I would never call myself 100% Ukrainian, the term “Canadian” seems so ambiguous to me as well. So I guess what I am trying to say is that I feel it is completely problematic that certain ethnicities are expected to obtain certain levels of their culture just because their physical appearance calls for that. No one has ever questioned my Canadian identity, but I don’t think that makes me any less sure about what being Canadian really means.