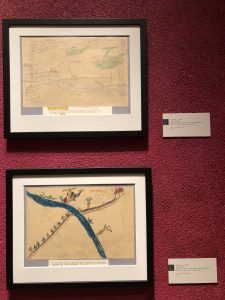

Leiba, Luis. Drawing, C. 1983. Pencil, crayon, ink, paper, plastic. Arts and Resistance Collection. Honduras, Mesa Grande Camp.

Does your object illustrate or help you better understand a concept you have studied in any of your CAP courses so far? Introduce the concept and show how it connects to the object and what we can learn by thinking about it this way

While walking through the Museum of Arts and Resistance Gallery, I was drawn to the Salvadoran children’s artistic depictions of their time waiting in the refugee camps. From examining the drawings, feelings of sorrow and pain were reflected in the children’s traumatic childhood pieces. The blank yellow paper which –for most North American children would draw familiar scenes like a happy family— were instead filled with helicopter bombings and deaths of their relatives. The typical North American children’s caption of, “My Family of Five”, were instead replaced with descriptions such as, “In the Lempa River, the soldiers made a massacre and killed many children, old, people and women. They burned the places where we used to live” (Leiba 1983). It is disheartening knowing these young Salvadoran refugees had already experienced such distress in their short lifetime. Regardless of ethnicity or nationality, parents and people alike strive to protect and ensure a child’s youth be joyous, stress-free, and safe. Unfortunately, this desire was not easily afforded to the parents of the 1980s Salvadoran refugees who experienced such pain and horror that no one, let alone a child, should ever encounter in their lifetime.

Despite the horror the Salvadoran refugees experienced during the bombings near The River Lempa, perhaps a silver lining to the refugee’s experience could be found by relating it to Benedict Anderson’s concept of what builds a society. Undeniably, the Salvadoran refugees suffered a great deal of agony living through cruel warfare. However, considering Anderson’s theory, our identity is deeply rooted in our historical past (Anderson 1982). The history and identity of being Salvadoran was perhaps strengthened through difficult times. Through the experience of warfare, one can share their collective hurt and transform it into a common ground with those who have gone through the same trauma, resulting in a greater sense of community and identity (Anderson 1982). There is a great sense of comfort in knowing that you do not stand alone and that there is someone else who has gone through what you have gone through. People who have undergone traumatic experiences are able to relate and understand other’s similar trials because they too have been through it themselves. By having similarities like being Salvadoran and carrying that traumatic history, a certain trust and commonality is shared when meeting another Salvadorans, despite being strangers. History is able to shape our identity, while a common history also creates a building block for relationships to form. It is important to acknowledge the past, especially those that are traumatic, and acknowledge them for what they are. However, it is imperative to acknowledge the role history plays in shaping present identities as well as serving as a familiar ground for cultures and communities to connect.

Misery and heartache possess the ability to blossom new relationships and experiences. In knowing that there is a comforting prospect to any situation, the Salvadoran children and Anderson’s ideology provide a helpful reminder for those who feel like there is no light at the end of the tunnel.

CITATIONS:

Anderson, Benedict R. OG. Imagined Communities. 1982.

Leiba, Luis. Drawing, C. 1983. Pencil, crayon, ink, paper, plastic. Arts and Resistance Collection. Honduras, Mesa Grande Camp.