Let Art Talk

Nov 25th, 2009 by eaduguay

“Art is not a luxury as many people think. It is a necessity. It documents history: it helps to educate people and stores knowledge for generations to come.” – Dr. Samella Lewis

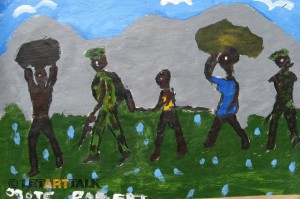

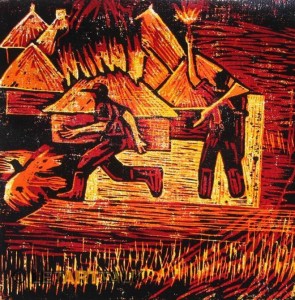

There have been several posts that have reflected on art as a form of expression and communication for the subaltern, which I have found particularly interesting, and reminded me of a memory from my childhood. When I was in grade six, my teacher took my class to a gallery exhibit featuring artwork done by child soldiers and brides, accompanied by short written stories and biographies. I remembered being quite affected by this experience, because I had never been exposed to life stories such as these before. Their drawings appeared just like my friends’ and mine, except for that under a closer look, the imagery of war and exploitation was woven into the various scenes. The art and written pieces were wrought with this sense of normalcy, and I couldn’t understand how such mistreatment was considered a typical part of life. Wondering about these kids who were somewhere else in the world, I felt badly for them and I felt badly that my life was so comfortable in comparison. I know that the pity and guilt I felt are problematic, but I really appreciated the opportunity my teacher gave my class to be exposed to other perspectives, to put ourselves in unfamiliar positions and to make a connection to kids like us, living under different circumstances in the world.

I searched to find this project, but instead I happened upon Let Art Talk, which is an organization launched in 2007 that uses art to educate and empower communities in northern Uganda. Their mission is, “to take art to grassroots communities as well as ensure that art is used as a vehicle for constructive change in the lives of ordinary people” (LAT website). The organization was founded by internationally acclaimed Ugandan artist Fred Mutebi, and uses art as a form of therapy, a tool for empowerment and education, and a communicative device for underprivileged communities in Uganda affected by social problems associated with HIV/AIDs, war, poverty, child abuse, and environmental issues.

The video is an account of a workshop held at the Laroo Primary School for children who were affected by the war in the North that took place in spring 2009. I was initially drawn to the first video because of its simplicity, naturalness, and sparse dialogue, which I thought might leave room to ‘let art talk.’ A large portion of the video has very faint, non-translated audio, and focuses on showing the artwork that has been made at this workshop. It is interesting to observe the interactions of the workshop participants and community members, and to see the various works of art, along with some of the process of their creation. There are sections where two men involved in the project speak briefly. The first is Vincent Okuja, who is the artist in residence and coordinator for this workshop and he speaks at 4:00, and organization-founder Fred Mutebi, speaks at about 5:40. Vincent is a university educated artist, and he discusses how this one year project helps to develop different skills for the students, and serves a therapeutic purpose for those children who are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Fred, who also has a university education, speaks of taking artists out of their studios and putting them in the community, how this project aims to help kids to garner skills necessary to return to their villages after being so affected by war.

As I mentioned previously, I found the amateur quality and simplicity of the video to be beneficial in helping to ‘hear’ those in the video. The viewers are able to look at the artwork and observe parts of the workshop in action. There is a lengthy portion that documents the art that has been made, allowing viewers to take in a broad overview of the art pieces. However, the quality of the video makes one very aware of the filmmaker, as the subjects in the video at times seem to interact with him or her. The ability to sit at home on the computer and feel like you are there first-hand began to feel a little strange to me as I watched the clip a few times. I felt a little odd, and wondered about the person behind the camera, and what the implications of their viewpoint would be. It seems that the cameraperson is Charlotte Harvey, who appears to be a white, North American woman. One cannot be sure as to her connection to Let Art Talk, her purpose in the making this video, her intended audience, and how that influenced her capturing and editing of the footage. I believe that she tried to give a natural, simple representation of the workshop. Yet still, the representation has been shaped in accordance to her position, and she, being the filmmaker has power over this representation.

As we have discussed in class and on the blog, it becomes complicated to define the voices like that of Fred Mutebi and Vincent Okuja as definitively ‘subaltern’ due to their university educations and their ability to speak English. Also, their voices meet us in the centre, as they translate their messages from their first language, making it easier for a Western audience to understand, and then this message is presented through video. Yet still, their voices are very valuable in presenting alternative perspectives and are richly complicated due to the intersectionality of their identities, as native-born Ugandans, artists, university educated males with a multiplicity of experiences. In fact, their complex identities have positioned them in a way that has allowed them to create connections, and make space to let others speak and express themselves.

I think the children and community members shown in this video are subaltern due to their marginalization by experiences of war and poverty, and it might be that Let Art Talk is meeting them at the periphery. Let Art Talk comes to rural Uganda, and presents the materials, guidance and environment to allow various subaltern, or marginalized people to express themselves. The website uses the word ’empower’ frequently, and as Sara has mentioned there is a danger of the concept of ‘giving power’ or ‘giving voice’ to others, due to the creation of donor-receiver power relations. The methods of expression are guided by the organization, and thus truly subaltern voices and uninfluenced expression might not arise out of this approach, but I think the value in creating the opportunity to ‘speak’ through art is quite high, as well as the proposed therapeutic and communicative benefits of their workshops and projects. Let Art Talk is founded by a man who grew up in rural Uganda, yet the organization has ties to the US, so it is hard to say how much the organization has been influenced by forces within Uganda and from the US, and what these influences entail.

Just as the subaltern voice is always in translation, so is art. Art is translated from the artist’s imagination to the observer; it is translated across class, race, gender, culture and an infinite list of identities. Every individual can interpret a piece of art differently, which complicates how messages are transferred. However, there is definitely a component of universality to art, and it has incredible value as a communicative tool despite potential complications. I think it would be easy to romanticize this project, and to fail to question its effectiveness in creating real positive change. It has only been operating since 2007, so it will be interesting to see what the lasting effects on the communities it has worked with will be.

In regards to the project, which would be incredibly interesting to further evaluate in terms of what we have studied in class, the link to the website is http://letarttalk.org/home.html and the youtube channel is https://www.youtube.com/LetArtTalk for more videos.

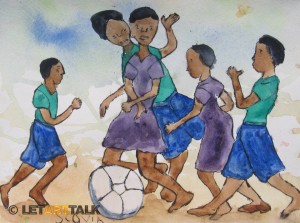

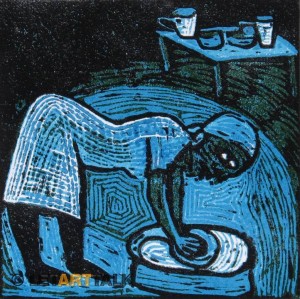

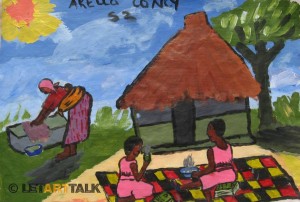

Here are some samples of artwork done by a diverse group of Ugandan children through Let Art Talk’s workshops.

I think that the video and project leave a lot of questions about what happens when you let art talk, what art can say, and how art is heard.

10 Responses to “Let Art Talk”

I really liked this video. The fact that there was little talking besides some interviews added to the overall goal of the project that the art should be and is doing the talking.

I strongly believe that art is an important form of speech and can say what would take thousands of words to explain. In any form of visual art, the speaker can use colors, shapes, textures, lighting, and more to convey their emotions and portray events. For example, a child saying “my father was killed” is much less affecting than that child’s painting of the murder. Our eyes tell so much more than our language.

This is another important point– art does not have any language barriers. This makes it a much more accessible and long reaching form of speech than talking. You don’t need a translator to get the story from a young man about an attack on his village.

i also believe that art is a great way to communicate. a picture or painting can symbolize so many things. Anybody can make art and they can make it out of anything. Therefore, anybody even the subaltern can speak out in this form. Also, as Olivia mentioned in the comment above, art does not have any language barriers. I think this point is very important. Also, any culture or believes can be represented and expressed. I think this way, anyone can see and interpret this art and hear what the artist is portraying

I think the whole idea of therapeutic art is amazing because it is co-beneficial for both the artist and the people viewing the art. It is a mode of relief and expression for the artist while for the viewer it is a form of appreciation and education. Art programs are especially relevant in war torn countries I think, one in particular, Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka’s civil war, a war that lasted for about 26 years, just ‘ended’. I say ‘ended’ because the most crucial part of peace building is now, to make sure that minority areas that have been systematically separated for decades can be heard and reintegrated. Art programs have become extremely popular in Tamil areas, using the theme, “What is Peace?” In a country torn dominantly by two languages, art can be, as Elizabeth said: translated. It is literally a mode of communication. These projects aren’t just about expression, they are about bringing lasting peace to a country. Another example of this is a program called “Peace through Art”:

http://www.icaf.org/programs/peacethroughart/default.html

The point I’m trying to make is that I think the value of art in development discourse is underrated. The West is so focused on quantifiable outcomes when it comes to big D development that art is not given enough credit. Although when you look at programs like Let Art Talk and Peace Through Art, they are significant to giving a voice to the subaltern and therefore building on development discourse.

Art is an amazing tool for people of all privileges to explore; a person’s work is often an extension of themselves and their experiences. Using art to express the subaltern’s voice is beneficial in many forms, but I believe that there is an inherent danger in using art as one’s sole means of expression. Art can be susceptible to misinterpretations; displaying one’s art may lead people to interpret a different story. It is however, in some circumstances the only way for one to express their voice and must be utilized. In closing I feel art as visual representations is a strong tool to express one’s voice, yet, it must but understood that the message they intended to express in their art may be misinterpreted by some audiences, altering their message.

I agree that art is a unique tool that the subaltern can use to speak out and have their voices heard, because art does not require a translation of language in order to be understood. However, as mentioned in Lizzy’s post and in previous comments, art can nonetheless be interpreted in many different ways, and often the result is a misinterpretation of the artist’s message. I think this is an example of the expression, “can we hear the subaltern”? Because even though the subaltern is speaking through art, it is questionable as to whether we can fully comprehend their message, due to differencs in culture and experience. Nonetheless, art is unique because it is unlike other instances, such as song, where someone must translate the words, and therefore that individual holds some power over the subaltern’s voice. I feel that this project, “Let Art Talk” is empowering because there is no ‘middle man’, so to speak, who explicitly interprets the subaltern’s voice for us.

This is probably my favorite vlog post; I loved its simplicity, and its ability to make me feel as if I were there. Like Lizzy said, the video allows the viewer to have “the ability to sit at home on the computer and feel like you are there first-hand”. This trait that the video has I feel is very powerful in getting the point across. Not only does art act as a therapeutic tool for the artist, it also allows for the subaltern to speak in an interesting and thought provoking way.

As it was mentioned before, there is a problematic aspect in art that gives the viewer full power of interpretation. Although this can be seen as an issue, I believe that is the point of the project. “Let art talk”, let art speak to you as a viewer; let it touch you in whichever way you choose to allow it. Letting the viewer create their own interpretation without so much as muttering a word, is probably one of the most powerful ways to “speak”. From all that we have learned this term in class, I have found that one of the most problematic issues with development and north-south relations is discourse itself. Words and the way that they are used have in essence created the “us-them” reality. Art does away with discourse. Rather than telling the viewer what you want them to take from the conversation with words, art allows for a more intimate and emotional connection between “speaker” and audience.

Let Art Talk seems to be a great organization, I especially like the fact that it was started by a Ugandan artist as it is a refreshing departure from the model of projects in the South developed by actors in the North. Initially I had some reservations as to the value of the project as a voice for the subaltern. There is no doubt in my mind of the value of art for the person who is making it, but I feel like the power of understanding resides entirely with the observer, thus the intended message may not be communicated accurately. Talking about the video, I share the same sentiment as a lot of the comments about how great it is shot. It isn’t trying to tell us anything in particular, but rather is showing us what its is they’re involved in.

I really enjoyed reading this post about Let Art Talk and the following comments. I am the US coordinator for Let Art Talk and have traveled to Uganda many times to work with the organization and visit my good friend Fred Mutebi.

Feel free to contact me if you would like to know any more information about Fred Mutebi or Let Art Talk.

Fred Mutebi Website

http://www.fredmutebi.org/

Fred Mutebi Facebook

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Fred-Mutebi/82339406425

Michael Kirkpatrick

Dallas, USA

Another artist that perhaps work to “letting art talk” in a different sense is Yinka Shonibare. He undertook the theme of re-writing the history as recorded and documented by the dominant colonial powers. In a series of three paintings from the “Effnick” series, he recreates aristocratic scenes of 18th century gentlemen, though he takes the place of the white aristocrat that one would expect to animate such a scene. His portraits draw attention to the ways that one can read colonialism into the portraiture that was so popular at the time (as those who are represented in the portraits are most likely to hold vast holdings of colonial land).

His other works are also really interesting—he often worked with fabrics that have come to be identified as “African” but are not authentically so. Interestingly, these fabrics were produced by the Dutch in the 19th century, then by the English for sales to the African market. Shonibare’s work situates them in a history of colonial appropriation of ethnic identity. I think the ties to Harvey’s article about how culture is eventually commodified and circulated as currency within the capitalist system very intriguing. The fabrics that are taken to be authentically “African” are themselves displaced and mass-produced.

There are times when he uses these fabrics to restage famous paintings in the Western canon of art history, only that a headless mannequin wearing a dress of faux African fabrics replaces the original subjects of the paintings. This way the history of colonialism is bluntly casted into the history of Western art.

While art can be used as a tool for communication, we must remember that within the Global North art is viewed as a commodity. In valuing the artisitc process within developing countries as a means through which the subaltern can speak, we are simply reinforcing our conception of art as a valued commodity. By imposing our values and exoticizing the artistic process, we interpret it in Western terms and therin lies potential for confusion as to the intended meaning of the art itself. Is it really theraputic to the people that are producing the art, or is it acting as a reassurance to the people producing this video so that they can feel better about a positive impact they may be having in these locales. Art can have a positive affect, conveying the emotions and experiences of the subaltern, but there is potential for the message of the art to be misinterpreted by the viewer, and the theraputic impact that we consider the art to possess may not be shared by the subaltern people who produce the art.