“Art is not a luxury as many people think. It is a necessity. It documents history: it helps to educate people and stores knowledge for generations to come.” – Dr. Samella Lewis

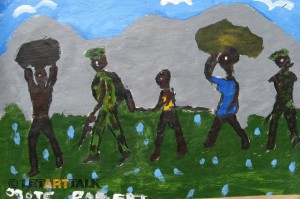

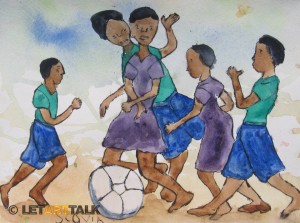

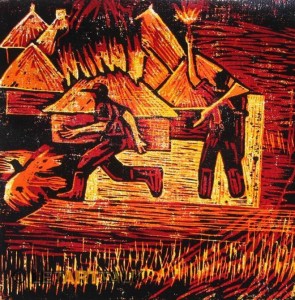

There have been several posts that have reflected on art as a form of expression and communication for the subaltern, which I have found particularly interesting, and reminded me of a memory from my childhood. When I was in grade six, my teacher took my class to a gallery exhibit featuring artwork done by child soldiers and brides, accompanied by short written stories and biographies. I remembered being quite affected by this experience, because I had never been exposed to life stories such as these before. Their drawings appeared just like my friends’ and mine, except for that under a closer look, the imagery of war and exploitation was woven into the various scenes. The art and written pieces were wrought with this sense of normalcy, and I couldn’t understand how such mistreatment was considered a typical part of life. Wondering about these kids who were somewhere else in the world, I felt badly for them and I felt badly that my life was so comfortable in comparison. I know that the pity and guilt I felt are problematic, but I really appreciated the opportunity my teacher gave my class to be exposed to other perspectives, to put ourselves in unfamiliar positions and to make a connection to kids like us, living under different circumstances in the world.

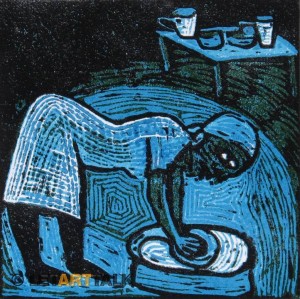

I searched to find this project, but instead I happened upon Let Art Talk, which is an organization launched in 2007 that uses art to educate and empower communities in northern Uganda. Their mission is, “to take art to grassroots communities as well as ensure that art is used as a vehicle for constructive change in the lives of ordinary people” (LAT website). The organization was founded by internationally acclaimed Ugandan artist Fred Mutebi, and uses art as a form of therapy, a tool for empowerment and education, and a communicative device for underprivileged communities in Uganda affected by social problems associated with HIV/AIDs, war, poverty, child abuse, and environmental issues.

The video is an account of a workshop held at the Laroo Primary School for children who were affected by the war in the North that took place in spring 2009. I was initially drawn to the first video because of its simplicity, naturalness, and sparse dialogue, which I thought might leave room to ‘let art talk.’ A large portion of the video has very faint, non-translated audio, and focuses on showing the artwork that has been made at this workshop. It is interesting to observe the interactions of the workshop participants and community members, and to see the various works of art, along with some of the process of their creation. There are sections where two men involved in the project speak briefly. The first is Vincent Okuja, who is the artist in residence and coordinator for this workshop and he speaks at 4:00, and organization-founder Fred Mutebi, speaks at about 5:40. Vincent is a university educated artist, and he discusses how this one year project helps to develop different skills for the students, and serves a therapeutic purpose for those children who are suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Fred, who also has a university education, speaks of taking artists out of their studios and putting them in the community, how this project aims to help kids to garner skills necessary to return to their villages after being so affected by war.

As I mentioned previously, I found the amateur quality and simplicity of the video to be beneficial in helping to ‘hear’ those in the video. The viewers are able to look at the artwork and observe parts of the workshop in action. There is a lengthy portion that documents the art that has been made, allowing viewers to take in a broad overview of the art pieces. However, the quality of the video makes one very aware of the filmmaker, as the subjects in the video at times seem to interact with him or her. The ability to sit at home on the computer and feel like you are there first-hand began to feel a little strange to me as I watched the clip a few times. I felt a little odd, and wondered about the person behind the camera, and what the implications of their viewpoint would be. It seems that the cameraperson is Charlotte Harvey, who appears to be a white, North American woman. One cannot be sure as to her connection to Let Art Talk, her purpose in the making this video, her intended audience, and how that influenced her capturing and editing of the footage. I believe that she tried to give a natural, simple representation of the workshop. Yet still, the representation has been shaped in accordance to her position, and she, being the filmmaker has power over this representation.

As we have discussed in class and on the blog, it becomes complicated to define the voices like that of Fred Mutebi and Vincent Okuja as definitively ‘subaltern’ due to their university educations and their ability to speak English. Also, their voices meet us in the centre, as they translate their messages from their first language, making it easier for a Western audience to understand, and then this message is presented through video. Yet still, their voices are very valuable in presenting alternative perspectives and are richly complicated due to the intersectionality of their identities, as native-born Ugandans, artists, university educated males with a multiplicity of experiences. In fact, their complex identities have positioned them in a way that has allowed them to create connections, and make space to let others speak and express themselves.

I think the children and community members shown in this video are subaltern due to their marginalization by experiences of war and poverty, and it might be that Let Art Talk is meeting them at the periphery. Let Art Talk comes to rural Uganda, and presents the materials, guidance and environment to allow various subaltern, or marginalized people to express themselves. The website uses the word ’empower’ frequently, and as Sara has mentioned there is a danger of the concept of ‘giving power’ or ‘giving voice’ to others, due to the creation of donor-receiver power relations. The methods of expression are guided by the organization, and thus truly subaltern voices and uninfluenced expression might not arise out of this approach, but I think the value in creating the opportunity to ‘speak’ through art is quite high, as well as the proposed therapeutic and communicative benefits of their workshops and projects. Let Art Talk is founded by a man who grew up in rural Uganda, yet the organization has ties to the US, so it is hard to say how much the organization has been influenced by forces within Uganda and from the US, and what these influences entail.

Just as the subaltern voice is always in translation, so is art. Art is translated from the artist’s imagination to the observer; it is translated across class, race, gender, culture and an infinite list of identities. Every individual can interpret a piece of art differently, which complicates how messages are transferred. However, there is definitely a component of universality to art, and it has incredible value as a communicative tool despite potential complications. I think it would be easy to romanticize this project, and to fail to question its effectiveness in creating real positive change. It has only been operating since 2007, so it will be interesting to see what the lasting effects on the communities it has worked with will be.

In regards to the project, which would be incredibly interesting to further evaluate in terms of what we have studied in class, the link to the website is http://letarttalk.org/home.html and the youtube channel is https://www.youtube.com/LetArtTalk for more videos.

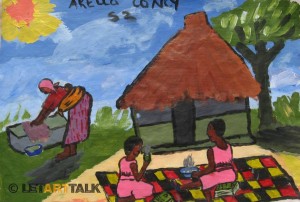

Here are some samples of artwork done by a diverse group of Ugandan children through Let Art Talk’s workshops.

I think that the video and project leave a lot of questions about what happens when you let art talk, what art can say, and how art is heard.