Water, perhaps more than any other single element, is an inherently multisensorial part of the landscape.

What are some examples of the multisensorial experience of water to consider in design?

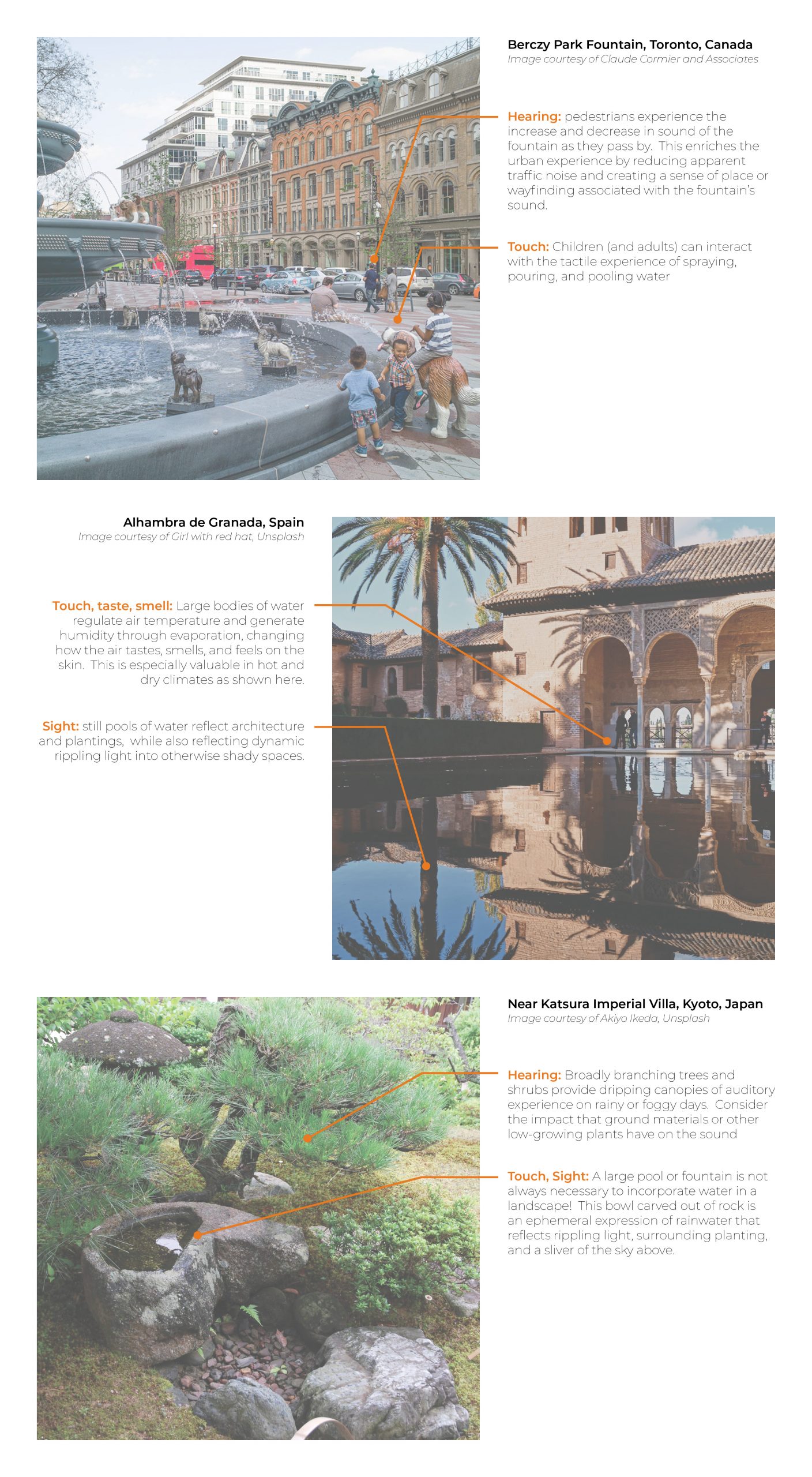

SOUND: water drips, splashes, rushes, ripples, and swirls, generating a varied range of sounds. Water also impacts the transmission of other sounds: the sound of flowing water or crashing waves may block out urban noise, while still water surfaces can reflect small sounds over great distances.

SMELL: Water impacts the experience of smell in its immediate surroundings. Imagine the smell of a damp forest compared to a dry one. Fast-moving water or mist often makes the surrounding air feel and smell fresh.

TOUCH: Our nerves do not have the ability to “feel” wetness, rather, they feel the difference in temperature between our skin and the moisture it comes in contact with (CITE). Submerging oneself in cool water or warm water has a very different effect, the former invigorating and the latter relaxing. The experience of moisture in the air, as well as the feeling of moving water passing through one’s fingers are important experiences to consider in the landscape.

TASTE: While not all water in the landscape can be tasted, some is intended for drinking and its taste may be considered as part of the purification process. Otherwise, there is a certain flavor to moisture in the air that is experienced in tandem with its smell.

SIGHT: Watching water ripple, rush, and form waves is an experience that offers relaxation. For hundreds of years, environmental designers have considered and revered water’s ability to reflect light – and therefore images. Many architects have used reflecting pools to cast ephemeral, rippling reflected light onto ceilings and walls. Water sparkles, forms droplets on leaves, freezes in frosty dustings or snowy white blankets, and dynamically images its surroundings.

Figure 1: Examples of Multisensorial Experience in Designed Landscapes

What are the benefits of proximity to water in the landscape in relation to wellbeing?

The multisensorial nature of water contributes to wellbeing throughout the human lifecycle. At a young age, the multisensorial nature of water applied to play aids in sensorial integration, an important milestone in infancy. As children grow, play, explore, and learn in water and wet, “messy” places, they develop motor skills and attention skills while encouraging imaginative play1. Engagement with wildlife that is drawn to watery landscapes further benefits childhood development2.

For adults in urban areas, water in natural landscapes contributes to wellbeing by encouraging passive attention, which has been studied as a way of reducing attention fatigue from the active attention required by the working urban life3. The sound of water is particularly good at masking urban noise, helping to create a sense of peace even in small city spaces.

Water in its various forms has been shown to be a critical aspect of encouraging biodiversity in the landscape (see the Water and Biodiversity blog post). Engaging with biodiverse landscapes and their active wildlife is also excellent for passive attention.

The concept of therapeutic landscapes, derived from the aforementioned active/passive attention theories, has been popularized since the 1990’s, and has intersections with culture and history, especially when related to water4. In many cultures and religions, water or certain bodies of water are considered sacred, and may be connected to concepts of healing and wellness. It is important to understand that water’s impact on wellbeing may go beyond universal science of the human body into the realm of more place-specific cultural and spiritual influences.

[1] Herrington and Brussoni, “Beyond Physical Activity.”

[2] White and Stoecklin, “Nurturing Children’s Biophilia.”

[3] Mooney, Planting Design: Connecting People and Place.

[4] Marques et al., “Therapeutic Landscapes.”

How can Environmental designers promote wellbeing through water-based interventions?

Environmental designers are in a unique position to incorporate water into their work in a way that promotes wellbeing. By understanding the intersections between universal and site-specific needs landscape architects can provide spaces to encounter water in the landscape that are accessible, variable, and biodiverse.

Environmental designers must endeavor to make water accessible (See also The Ethics of Water blog page). On an urban planning scale, this means ensuring that everyone is in close proximity to natural landscapes that include water. It is especially important that children have access to water that they can play in and near throughout their most critical developmental stages. At a smaller scale, environmental designers can design watery landscapes to be fully inclusive so that all members of a community can benefit from proximity to water. Interventions may be centered on the issue of access, for example, returning industrial properties along a river to public shoreline and constructing areas for recreation, fishing, or swimming. Water quality is a big part of ensuring accessibility, and should be considered in tandem.

When designing with water, employ variability in such a way that promotes a variety of multisensorial experiences. Consider how each of these experiences is felt and perceived by the visitor: for example, some sounds of water can be relaxing while others are energizing or even bothersome. Variability of sensory water experiences can be used to create a sense of place and aid in wayfinding.

Finally, note that the experience of water extends beyond the water itself to that which it affords in the landscape. One of these is the experience of biodiversity, which is becoming an increasingly important consideration for environmental designers. For more information on the importance of biodiversity in design, and how water plays a significant role, please visit the Water and Biodiversity blog page.

Sources

Marques, Bruno, Jacqueline McIntosh, Hayley Webber, Bruno Marques, Jacqueline McIntosh, and Hayley Webber. “Therapeutic Landscapes: A Natural Weaving of Culture, Health and Land.” In Landscape Architecture Framed from an Environmental and Ecological Perspective. IntechOpen, 2021. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.99272.

Mooney, Patrick F. Planting Design: Connecting People and Place. Routledge, 2020.

Zhang, Xindi, Yixin Zhang, Jun Zhai, Yongfa Wu, and Anyuan Mao. “Waterscapes for Promoting Mental Health in the General Population.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22 (January 2021): 11792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211792.

Herrington, Susan, and Mariana Brussoni. “Beyond Physical Activity: The Importance of Play and Nature-Based Play Spaces for Children’s Health and Development.” Current Obesity Reports 4, no. 4 (December 1, 2015): 477–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-015-0179-2.

White, Randy, and Vicki L. Stoecklin. “Nurturing Children’s Biophilia: Developmentaly Appropriate Environmental Education for Young Children.” Collage: Resources for Early Childhood Educators, November 2008. http://psichenatura.it/fileadmin/img/R._White__V._L._Stoecklin_Nurturing_Children_s_Biophilia.pdf.

Additional Resources

Roehr, Daniel. Multisensory Landscape Design: A Designer’s Guide for Seeing. London: Routledge, 2022. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429504389.

A helpful resource for designing with all the senses in mind – not just sight. Water is shown to play a role in multisensorial landscapes especially in Chapter 3: Sensewalks.

Zhang, Xindi, Yixin Zhang, Jun Zhai, Yongfa Wu, and Anyuan Mao. “Waterscapes for Promoting Mental Health in the General Population.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 22 (January 2021): 11792. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211792.

A research paper detailing the impacts of water in the landscape on human wellbeing through “mitigation (e.g., reduced urban heat island), instoration (e.g., physical activity and state of nature connectedness), and restoration (e.g., reduced anxiety/attentional fatigue)”.

Precedents

Fin Garden

Location: Kashan, Iran

A 16th century Persian garden recognized by UNESCO. Fin Garden’s extensive water features, run entirely on gravity, create a multisensorial wonderland of sound and touch, smell, and sight.

View Iran’s tourism site for the garden here, or see pages 67-70 in Daniel Roehr’s Multisensory Landscape Design (see Additional Resources) for a multisensorial breakdown.

Garden City Playscape

Richmond, BC, Canada

A natural playscape incorporating channelized and messy water: the range of ways for kids (and adults) to interact directly with water in this park illustrate how significantly water can contribute to multisensorial play and childhood wellbeing.

This project can be viewed here.