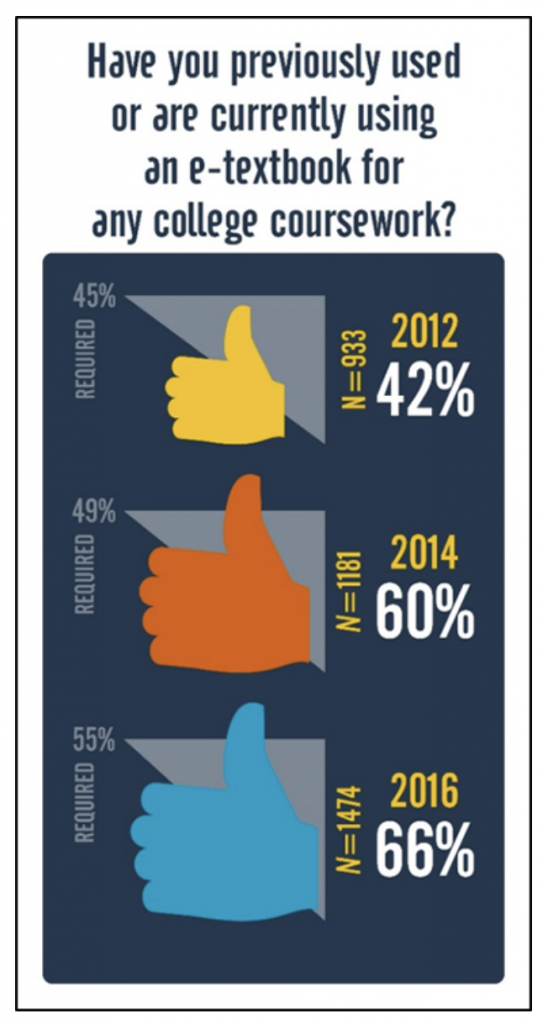

According to Vannevar Bush’s ideas in 1945, if digital books are defined as storable, personal library collections, they were first introduced to the world as early as 1949, referred to as “ebooks”. With the evolutionary transformation of portable electronic devices over the last century, the development of digital books has also made considerable progress in recent years. In May 2011, Amazon’s ebook sales surpassed those of paper books for the first time, proving that digital books are gradually replacing traditional printed books(Ha, 2019). An industrial analyst Watson (2018), estimates that digital publishing marks up to 19% of the book market after pulling disparate reports available in the public domain. Another estimate tracked by the Association of American Publishers also estimates that with a trade net revenue of $ $82.5 million in September 2019, eBooks (excluding self-published digital books) generated 10% of overall market sales (Association of American Publishers, 2019). Despite the fast growth of sales figures, various ebooks are increasingly appearing in different educational scenarios. K-12 teachers and parents began using interactive and engaging ebooks extensively to help learners pace their own learning progress towards complex concepts. In higher education, a multiyear quantitative study shows the increasing adoption rates of e-textbooks at the University of Central Florida from 2012 to 2016 as below figure (Raible & Denoyelles, 2017):

Not to mention that many educational institutions have offered distance learning to replace traditional onsite education under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic, digital books have become the most convenient and safe choices for teachers and students. Nowadays, digital books have already played a massive role in educational activities and will heavily influence the literacy development of younger generations.

The earliest invention of digital books is an electronic reference book, which was first introduced by converting from its printed versions, including bibliography, index, dictionaries, encyclopedias, guides, product catalogues, and maintenance manuals for various systems (Wilber, 2019). Electronic reference books come in the form of stand-alone or integrated databases that can be sorted and searched. In addition, CD-ROMs with specific programs or web-based information services are made available to readers. Rapidly, they have gained a foothold in the learning community, and readers and libraries have been widely used, which has replaced the long-held dominant position of printed copies. It is commonly recognized that the conversion of the reference books from hard copy to electronic was very successful. The reason for such success should be attributed to the different usability strengths between the reference book and ordinary books. First of all, electronic reference books allow readers to process information at a much faster speed. For example, when readers use a reference book, they usually search first, and then read a relatively short paragraph of specific text content, while when they read the hard copy, they will be reading the entire book page by page from the beginning to the end. Secondly, electronic reference books have a tremendous advantage over traditional hardcopies in updating information. The content of reference books usually needs to be continuously updated, revised, and expanded. Whereas ordinary books, once they are finalized, they are seldom updated. Thirdly, novel means of encapsulating knowledge and information have become available. Dynamic content expansion methods can be easily implemented in the electronic environment, which empowers the electronic reference tool books to have competitive advantages over their printed counterparts in terms of layout and content renewal.

The digitalization of magazines is also a successful case in the early stage (Wilson, 2014). In addition to the characteristics of distribution and price advantage, the editing method of electronic magazines is an essential feature that distinguishes electronic magazines from printed editions. Furthermore, it is also the most influenced by electronic magazines and computer network technology. The significance of electronic magazines has far exceeded the layout design itself. It involves various content presentation methods, the selection of hyperlinks, and the establishment and various additional services provided to readers. Based on Nielson’s (2003) definition of usability, it is a great leap forward in learning history since the digital magazine significantly improved design/writing methods and user/reading experiences. At this stage, more publishing and education communities recognize the usability potential of digital books for more practical purposes.

With the influence of the development of reference book databases and electronic magazines, and benefited from technological innovation and progress, by the mid-to-late 1980s, other books began to appear in the form of electronic versions. However, the early stage of the development of digital books has experienced a differentiated and challenging process (Wilber, 2019). In addition to the traditional reading habits mentioned above, the reasons for the difficulty in the development include the problems of displays, standards, environmental issues, and business and market issues. First of all, for some readers, it is imperative to write sticky notes, highlight, and take notes on the margin while reading. Unfortunately, early ebooks have done little to satisfy these people’s reading habits. Secondly, during the development of ebooks, it has undergone many technical updates. As a result, many ebooks that relied on a specific format or technology (e-readers) quickly became inaccessible and vanished from the market. In addition, the complexity of the computer and other hardware/software environment required to read an ebook compared to the simplicity and convenience of reading a manuscript or printed book is also daunting. Finally, as an emerging product, digital books’ ultimate success must depend on usability standards, including providing readers with a specific size and quantity of ebooks with eye-catching content, standardizing the conditions and regulations of use, while maintaining e-readers and digitals copies at a more reasonable price. Thus, early attempts at promoting digital books were mostly unsuccessful in these defects in affordance mentioned above.

From the beginning of this century, with astonishing advancements in information technology and the popularity of electronic devices, digital books have become more accessible for teachers and learners. Along with revolutionary shifts in education psychology, pedagogy and approaches, digital books present radical features in their usability. One of the leading North American companies that provide innovative learning technologies, summarizes four educative benefits of digital books, including proactive learning, self-paced interactive activities, videos and graphic explanation of abstract concepts, and ease of use for teachers to update/distribute content (Barquero, 2022). As an adult learner, I am also a fan of digital books for three reasons. Firstly, technological functions empower digital books to satisfy different learning needs, so I can use the audio feature to listen to the book while gardening or exercising. Secondly, digital books are highly accessible for carrying around, storing, and searching. The third and most important reason for me is that electronic books have great environmental significance in terms of sustainability compared to traditional paper documents.

By comparing and analyzing the various educational advantages of digital books over paper books, it is clear that this form of educational technology has already met five of the seven Usability Criteria proposed by Issa and Isaias (2015). They are learnability, flexibility, robustness, efficiency and memorability. Therefore, it is not surprising why digital books have been gradually replacing paper books for educational purposes over the last two decades. In addition, this change in educational technology has been even more dramatic in the last three years. Because of the epidemic’s impact, most schools that closed their onsite learning began to explore the possibility of distance learning. As an essential part of online education, digital learning materials have to be widely accepted for global health concerns, whether teachers and students are satisfied with this solution.

In fact, responsible education practitioners have been continuously working on the implications of digital books conducted. While some studies show that digital books do support literacy learning for young children (Korat & Shamir, 2008, 2012; Roskos, Sullivan, Simpson, & Zuzolo, 2016), others suggest they do not (Jones & Brown, 2011; Trushell, Burrel, & Maitland, 2001). Ly (2019) believes the main driving factor in opposite conclusions is the degree of effectiveness in each set of researcher-designed ebooks. The difference in qualities of digital publishing has concerned educators in selecting for younger students. Furthermore, there is a lack of research on the effects of more abundant interactive features on today’s handheld electronics in the children’s learning environment (Yokota & Teale, 2014). As Citton (2017) explained the term “Mediachy”, we now live in an age of information explosion. Even for adults, properly manage their attention to focus on reading and learning can be a challenging task which requires judgment and execution. So for younger learners, is reading digital books on digital devices a better overall learning experience? Do they get distracted by the amount of information on their electronic devices? Do interactive activities on digital books distract students from learning knowledge? These questions and controversies arise along the rapid development of digital books, and they will continue to be the main driving forces for advancing the educational affordance of digital books in the future.

References:

Association of American Publishers. (2019). Association of American Publishers Release September 2019 Statshot Report. https://newsroom.publishers.org/association-of-american-publishers-releases-september-2019-statshot-report/

Barquero, J. (2022). 6 Reasons to Start Using Digital Books in Educational Centers. CAE. https://www.cae.net/6-reasons-to-start-using-digital-books-in-educational-centers/

Bush, V. (1945). As We May Think. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1945/07/as-we-may-think/303881/

Citton, Y. (2017). Introduction and Conclusion: From Attention Economy to Attention Ecology. In The Ecology of Attention. John Wiley & Sons.

Ha, T.-H. (2019). Are ebooks dying or thriving? The answer is yes. Quartz website. https://qz.com/1240924/are-ebooks-dying-or-thriving-the-answer-is-yes/

Issa T. & Isaias P. (2015) Usability and human computer interaction (HCI). In Sustainable Design (pp. 19-35). Springer, London. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.1007/978-1-4471-6753-2_2

Jones, T., & Brown, C. (2011). Reading engagement: A comparison between e-books and traditional print books in an elementary classroom. International journal of instruction, 4(2).

Keep, C., McLaughlin, T., & Parmar, R. (2000). Sony Data Discman. http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/elab/hfl0014.html

Korat, O., & Shamir, A. (2008). The educational electronic book as a tool for supporting children’s emergent literacy in low versus middle SES groups. Computers & Education, 50(1), 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2006.04.002

Korat, O., & Shamir, A. (2012). Direct and Indirect Teaching: Using e-Books for Supporting Vocabulary, Word Reading, and Story Comprehension for Young Children. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 46(2), 135–152. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.46.2.b

Ly, C. N. (2019). Where are we now? reconsidering interactive text features and their role in the classification of digital books as considerate or inconsiderate. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. http://ubc.summon.serialssolutions.com/

Lebert, M. (2011). eBooks: 1998 – The first ebook readers. Project Gutenberg News. http://www.gutenbergnews.org/20110716/ebooks-1998-the-first-ebook-readers/

Nielsen, J. (2003). Usability 101: Introduction to usability. Useit. http://www.ingenieriasimple.com/usabilidad/IntroToUsability.pdf

Raible, J., & Denoyelles, A. (2017). Exploring the Use of E-Textbooks in Higher Education: A Multiyear Study. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2017/10/exploring-the-use-of-e-textbooks-in-higher-education-a-multiyear-study

Roskos, K. A., Sullivan, S., Simpson, D., & Zuzolo, N. (2016). E-Books in the Early Literacy Environment: Is There Added Value for Vocabulary Development? Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 30(2), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2016.1143895

Trushell, J., Burrell, C., & Maitland, A. (2001). Year 5 pupils reading an “Interactive Storybook” on CD‐ROM: losing the plot?. British journal of educational technology, 32(4), 389-401.

Watson, A. (2018). E-books – Statistics & Facts. Statista. https://www.statista.com/topics/1474/e-books/

Wilber, J. (2019). A Brief History of eBooks. TurboFuture. https://turbofuture.com/consum