Fig.1. A mother and her children at a shelter via getty images

Social exclusion is the process in which individuals or people are systematically blocked from (or denied full access to) various rights, opportunities and resources that are normally available to members of a different group, and which are fundamental to social integration and observance of human rights within that particular group (e.g., housing, employment, healthcare, civic engagement, and democratic participation). It is important to say that income poverty is not necessarily the cause that introduce vulnerability to social exclusion. There are other factors such as involuntary layoff, divorce and gender which have an effect towards (or promote) social exclusion. Unfortunately, the Japanese government has been reluctant to acknowledge poverty and social exclusion as a social issue.

There are several studies dedicated to Social Exclusion which are demonstrated through this file : Selected Empirical Studies of Social Exclusion

Income, Social Factors and Social Exclusion

In Japan, social exclusion has resulted from economic poverty and the decline of informal mutual aid which in 2013, the Japanese government recorded relative poverty rates (population living on less than half of the national median income) of 16% which was the highest on record. It has been seen that the decrease of low-rent dwelling, company residences and social housing is the prime reason behind the lack of access to suitable housing for the low income group. Furthermore, living alone or just the size reduction of household contributes to increased in vulnerability to social exclusion. However, even the age group with the highest vulnerability showed a discrepancy between income poverty compared and social exclusion. There are other factors like involuntary getting fired and getting a divorce contribute to social exclusion.

Child Poverty and Social Exclusion

With regard to poor children in Japan, it has been estimated that 3.5 million Japanese children – or one in six of those aged up to 17 belong to households that are experiencing poverty. There seems to be a strong causality when it comes to a lower standard of living or child poverty leading to social exclusion in adulthood. As disadvantages at earlier stages of life seem to have influence on social exclusion, even if they have stable income, job and a decent household to stay in.

Childhood disadvantages such as family structure, occupational class, employment of father and financial hardships are correlated with negative adult incomes. Especially at the age of 15, a low standard of living have a significant effect on basic needs (food, clothing and medical care) despite even after having stable income, job and household, and having dealt with experiences of divorce, getting fired, illness and injuries. This shows that poverty hardship at a young age creates a path where childhood poverty and adult social exclusion directly.

Gender and Social Exclusion

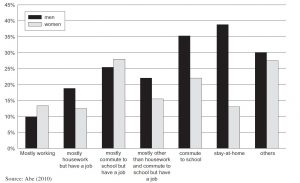

Fig.2. Poverty rates of the working age (20 to 64 years old) classified by employment status and sex (2007) via Poverty and Social Exclusion of Women in Japan

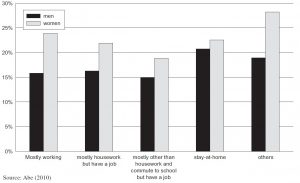

Fig.3. Poverty rates of the elderly classified by employment status and sex (2007) via Poverty and Social Exclusion of Women in Japan

1 out of 3 Japanese women in the age group of 20-64, and those who live alone, were living in poverty in 2010. There is an increasing data that shows the poverty risk of women is rising. Before “the working poor” was recognized only when it started to affect man, poverty among working women were already a common problem. In cases of men making all important decisions about the community where no women are present could be interpreted as being excluded from social participation as a group. Furthermore, women tend to engage much more in informal social interaction such as pornography than man, but is the opposite when it comes to formal social participation (e.g. political activities) shows that they are socially excluded from the mainstream society.

References:

Abe, A. K. (2012). Poverty and social exclusion of women in Japan. Japanese Journal of Social Security Policy, 9(1), 61-82.

Aoki, M. (2012). Poverty a growing problem for women. The Japan Times [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2012/04/19/national/poverty-a-growing-problem-for-women/#.WfUDM2hSzcc.

Aya K, A. B. E. (2009). Social exclusion and earlier disadvantages: An empirical study of poverty and social exclusion in Japan. Social Science Japan Journal, 13(1), 5-30.

McCurry, J. (2017). Japan’s rising child poverty exposes true cost of two decades of economic decline. TheGuardian [Website]. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jan/17/japans-rising-child-poverty-exposes-truth-behind-two-decades-of-economic-decline

Okamoto, Y. (2016). Japanese social exclusion and inclusion from a housing perspective. Social Inclusion, 4(4).