Last week I had the opportunity to visit UBC’s Rare Books and Special Collections (RBSC), where I was able to learn more about the gathering and importance of archival materials and even sift through several of their collections. I was intrigued to see firsthand how an assortment of materials (letters, documents, newspaper articles, photos, etc.) could be assembled to form a bigger picture — one which preserves history, identity, and culture. For example, the Douglas Coupland fonds contain items such as fan mail, press clippings, and visual arts projects — items which might not reveal much on their own, but collectively they tell the story of Coupland’s life and legacy. Evidently, the collection and preservation of archival documents is important in preserving collective memory.

But when it comes to the documentation of traumatic experiences or events, there is a question of both how much can be documented and how much should be documented, when considering the privacy of the individual. While Lauren Bratslavsky asserts that archival materials are important in “anticipating future research needs”, there must also be respect for the rights of the individual. Rodney G.S. Carter stresses the importance of respecting those who wish to “keep their own silence”. Finding this balance then becomes a challenge.

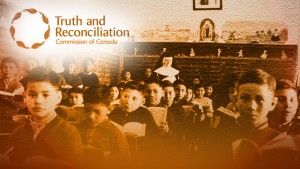

It has been a topic of debate on several occasions. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) has faced backlash from residential school survivors, who expressed confidentiality concerns regarding the archiving of their personal records — an issue that was brought to an Ontario Superior Court.

Events surrounding World War II and the Holocaust have also been extremely controversial. There has been much documentation throughout the time period, by the Nazi party especially. “17 million fates” were said to have been opened to the public when in 2006 Germany decided to release fifty million Nazi files documenting the lives and deaths of Jewish Holocaust victims.

The Holocaust was no less traumatic than the issue of residential schools in Canada; however, Germany’s decision to release these documents was met with much less backlash. Germany had held off for years due to fears of “privacy concerns”, but evidently had decided that enough time had passed for the documents to be released. Conversely, the residential school survivors were promised complete confidentiality and were given less time to heal before their information was threatened to be released. While historians, scholars, and the general public could certainly benefit from the knowledge and awareness that these documents would bring, I believe that the rights of the individual should be protected first. Perhaps with more time, as with Germany and the “Holocaust archives”, the stories of residential school survivors can one day be archived, although more discussion would certainly need to take place in order for this to happen.

Works Cited:

Bratslavsky, Lauren. American Journalism: The Archive and Disciplinary Formation: A Historical Moment in Defining Mass Communications. 32 Vol. American Journalism Historians Association, 04/03/2015. Web. 25 Jan. 2016.

Carter, Rodney G. S. “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence.” Archivaria.61 (2006): 215-33. Web. 25 Jan 2016.