by Simon Donner

We have been thinking a lot here about sea level rise, from the effect on tides to the UNESCO heritage sites at risk. If you search the media for the most recent IPCC sea level rise predictions, you’ll read that the 2013 report concluded that sea level was “likely” to increase by 45-82 cm by the “end of the century”. These numbers are misleading for two reasons, as was explained very well in a December letter to Science magazine by the very authors of the IPCC sea level rise chapter. The nuances may be important when making adaptation decisions.

First, what people present as “end of century” from the IPCC is, technically, an average of model-projected values for the year 2081 through the year 2100. Since sea level is expected to be rising rapidly at the end of the century – 8-16 mm/year, up to five times today’s rate – the difference between an average for those last twenty years and the value for actual end of the century is meaningful. The “likely” range for 2100 is actually 52 – 98 cm, not 45-82 cm.

Flooding in Ambo, Tarawa from “king” tide (ABC News)

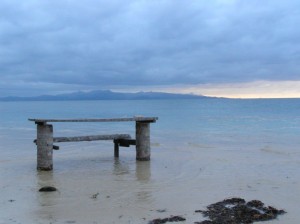

Those few extra centimetres could matter to low-lying places like Kiribati, Bangladesh, and even nearby Richmond, BC. For example, just three weeks ago, ocean waves from a low pressure system off Kiribati enhanced the spring or “king” tide peak by up to 10 cm. That was enough for flooding to cause major damage to homes, water sources and roads in Tarawa and neighbouring atolls.

Second, “likely” has a specific meaning in the climate parlance. I’ll let John Church and his IPCC co-authors explain:

In the calibrated uncertainty language of the IPCC, this assessed likelihood means that there is roughly a one-third probability that sea-level rise by 2100 may lie outside the “likely” range. ..

The upper boundary of the AR5 “likely” range should not be misconstrued as a worst-case upper limit… For policy and planning purposes, it may be necessary to adopt particular numbers as an upper limit, but according to our assessment, the current state of scientific knowledge cannot give a precise guide.

Coping with this uncertainty was the focus of our recent work on adaptation decisions in Kiribati. One key finding in the paper by Sophie Webber and I is that keeping a short-term planning horizon (which a consultant labelled te tibu or ‘for the grandchildren’) helps reduce the scientific uncertainty and hence the trade-offs between adaptation options. The reason is that the range of model predictions is far greater for 2100 than it is for 2030. However, planning only for the short-term biases towards easier, cheaper adaptation measures, and leaves the community unprepared to implement more complex or expensive measures.

That’s why there is value in doing two seemingly contradictory things: raising funds for immediate adaptation efforts while also planning for the worst case, end-of-century scenario based on the full range of the future projections. Places like Kiribati need to prepare locally for sea level change over the next few decades and lay the groundwork for international migration, in case the world ends up on the high end of that “likely” range – or beyond – at the actual end of the century.

Tad Pfeffer gave a talk a few years ago at the AGU annual meeting in S.F. He described a model he saw in New York at the Museum of Modern Art called “Rising Currents” which had been created to show what the plan was in New York to cope with 2m of sea level rise, if that happened by 2100.

He said he talked to the creators of the model: “I asked them, given the fact that if you anticipate 2 m by 2100 its pretty reasonable to expect 3 m by 2150. They had no plan. The plan was for a rise of 2m that stopped. It isn’t going to stop”.

Hansen talks about a civilization that is committing the planet to an ice free state. That seems to be a more reasonable way of talking about this.

Dean Jacobson captured some amazing footage of the storm surge and high tide event in Majuro, which is capital of the Marshall Islands and just north of Kiribati.

The video also tells the story of his being fired by the local college, most likely due to protesting a reef mining project proceeding without an environmental assessment. The reef mining did not specifically cause the waves and erosion seen in the video, but it is the type of activity that makes an island more vulnerable to high tides and storm surges.