Many regarded the acceptance in 2006 of the North Coast Land and Resource Management Plan (NCLRMP) as an example of successful planning and collaborative process (4)(6)(8)(10). The plan brought together a diversity of stakeholders and strived to create a model for sustainable development and natural resource management, particularly through the use of ecosystem-based management. Located on British Columbia’s north and central coast, the Great Bear Rainforest (GBR) is an ecologically significant area covering 6.4 million hectares of coastal temperate rainforest (6).

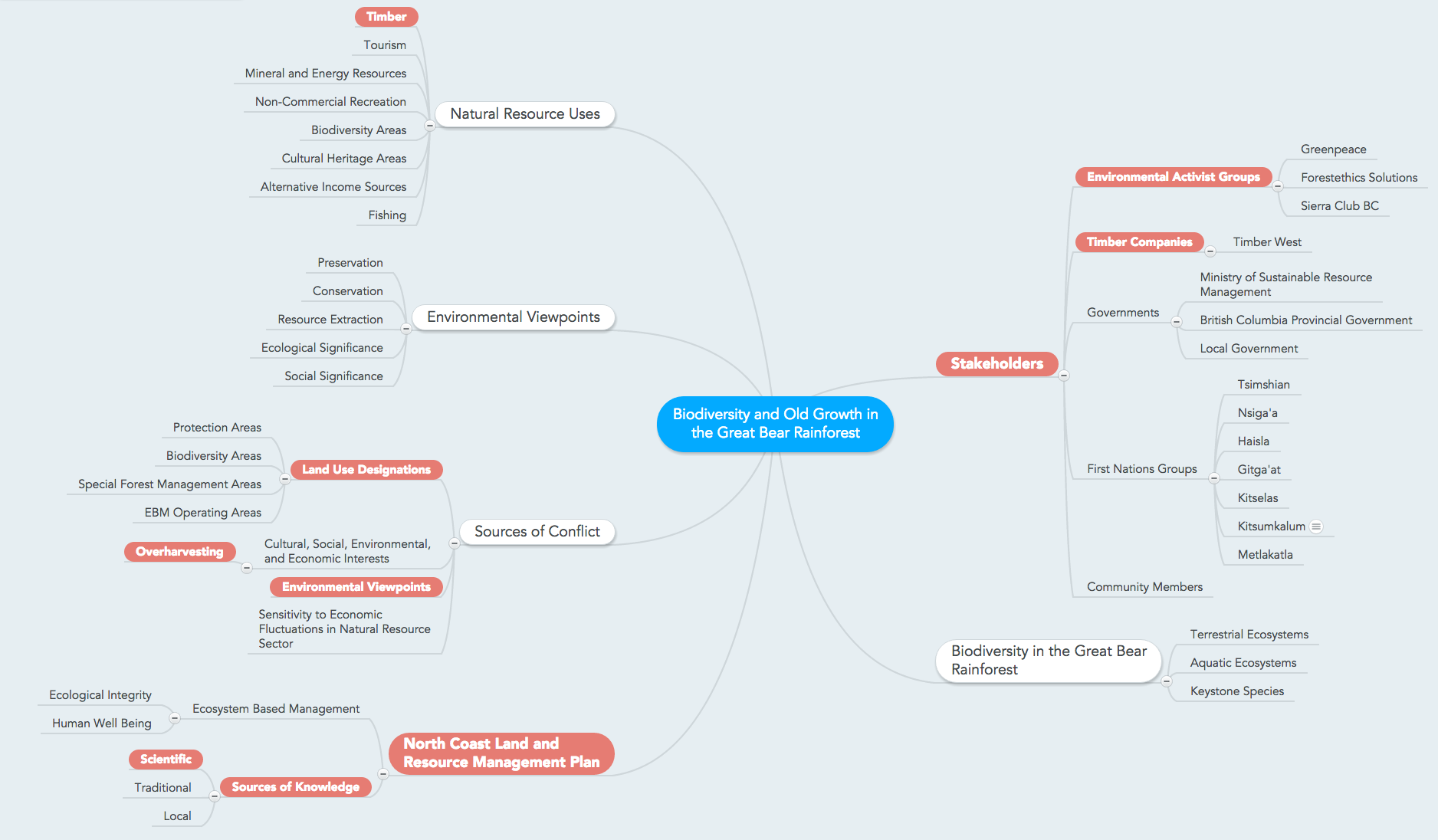

However despite the apparent success of the plan, issues surrounding biodiversity and old growth in the GBR including the logging of old growth forest by TimberWest continue to raise concerns (5) and possess many characteristics of wicked environmental problems (1). There is scientific uncertainty and value uncertainty surrounding the usage and protection of the aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems, leading to a complexity that is demonstrated in Figure 1.

By comparing some of the biophysical and social factors outlined in Figure 1 to the properties and outcomes of wicked environmental problems described by Balint et al (2011), we see that this issue can be characterized as a wicked problem.

- Multiple views: There are many stakeholders involved in the protection of the biodiversity in the GBR. These include timber and other resource extraction firms, environmental activist groups, various divisions of local and provincial government, First Nations groups, and community members. While there is some overlap of ideology between the stakeholders, each one possesses differing values, motivations and environmental viewpoints which conflict when solutions are sought. These value differences have been and continue to be one of the greatest sources of conflict in the area, and a major obstacle to positive cooperation and outcomes.

- Uncertainty: Ambiguity in the wording of the legislation has led to different interpretation by stakeholders guided by individual motivations (5). The result is conflict in the form of overexploitation of resources and fracturing of strong relationships between groups. Differences in variables being measured to illustrate efficacy of the plan results in scientific uncertainty.

- Unique: Both socially and scientifically. The area carries with it a long history of natural resource use by First Nations groups as well as aboriginal and treaty rights that are specific to this area. Additionally the ecosystems contained within the boundaries of the GBR and the interactions that exist within them are unique to the area, therefore requiring specific scientific research to support claims. While the practice of ecosystem-based management and bilateral negotiation may not be unique to this issue, the interaction of specific biophysical and social factors are (10).

- Persistent / Unstable: As with any ecosystem, the GBR is a dynamic system that is constantly changing. Scientific study must be constantly updated or undertaken over a long time scale to account for seasonal and climactic fluctuations, as well human caused alterations to the environment such as those disruptions created by industry (e.g. intensive logging or fishing). As a result, any legislation pertaining to the protection of the biodiversity and old growth forests must also accommodate changes in scientific findings and social shifts.

Figure 1 is a mind map outlining the complex nature of these interactions. On the right are the various stakeholders who played a part in the creation of the NCLRMP, including the major First Nations groups and predominant environmental activist groups. Sources of conflict (left) arise between these stakeholders due to differing environmental viewpoints (left), cultural / social / economic interests, and sensitivity to economic fluctuations. In addition to differences of values, different groups place worth in different natural resources and thus are motivated to provide protection differently. Natural resources uses include timber, biodiversity areas, and non-commercial recreation. The NCLRMP and Central Coast LRMP (not shown) have been highlighted as providing a potential framework for addressing this wicked problem, and also for the shortcomings that have already been experienced that have resulting in conflict between timber companies and environmental activists.

References:

(1) Balint, P. J., Stewart, R. E., Desai, A., & SpringerLink ebooks – Earth and Environmental Science. (2011). Wicked environmental problems: Managing uncertainty and conflict. San Francsico; Washington;: Island Press. doi:10.5822/978-1-61091-047-7

(2) B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, Coastal First Nations, Nanwakolas Council. (2012) Ecosystem based management on B.C.’s Central and North Coast (Great Bear Rainforest): Implementation Report. Retrieved from http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/public/pubdocs/bcdocs2012_2/522445/ebm_implementation%20update_report_july%2031_2012.pdf

(3) British Columbia Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management. (2005) North Coast Land and Resource Management Plan: Final Recommendations. Retrieved from https://www.for.gov.bc.ca/tasb/slrp/lrmp/nanaimo/ncoast/docs/NCLRMP_Final_Recommendations_feb_2_2005.pdf

(4) Clapp, R. A. (2004). Wilderness ethics and political ecology: Remapping the great bear rainforest. Political Geography, 23(7), 839-862. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2004.05.012

(5) Hume, M. (2015, July 27). Report chides TimberWest over old trees in the Great Bear Rainforest. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/report-chides-timberwest-over-old-trees-in-the-great-bear-rainforest/article25716089/

(6) McGee, G., Cullen, A., & Gunton, T. (2010). A new model for sustainable development: A case study of the great bear rainforest regional plan. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 12(5), 745-762. doi:10.1007/s10668-009-9222-3

(7) Ministry of Agriculture and Lands. (2009). Central and North Coast order. Retrieved from https://www.for.gov.bc.ca/tasb/slrp/lrmp/nanaimo/cencoast/docs/CNC_consolidated_order.pdf

(8) Price, K., Roburn, A., & MacKinnon, A. (2009). Ecosystem-based management in the great bear rainforest. Forest Ecology and Management, 258(4), 495-503. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2008.10.010

(9) Rittel, H.W.J., and Webber, M.M. (1973). Dilemmas in general theory of planning. Policy Sciences 4: 155-169.

(10) Saarikoski, H., & Raitio, K. (2012). Governing old-growth forests: The interdependence of actors in great bear rainforest in British Columbia. Society & Natural Resources, 25(9), 900-914. doi:10.1080/08941920.2011.642462