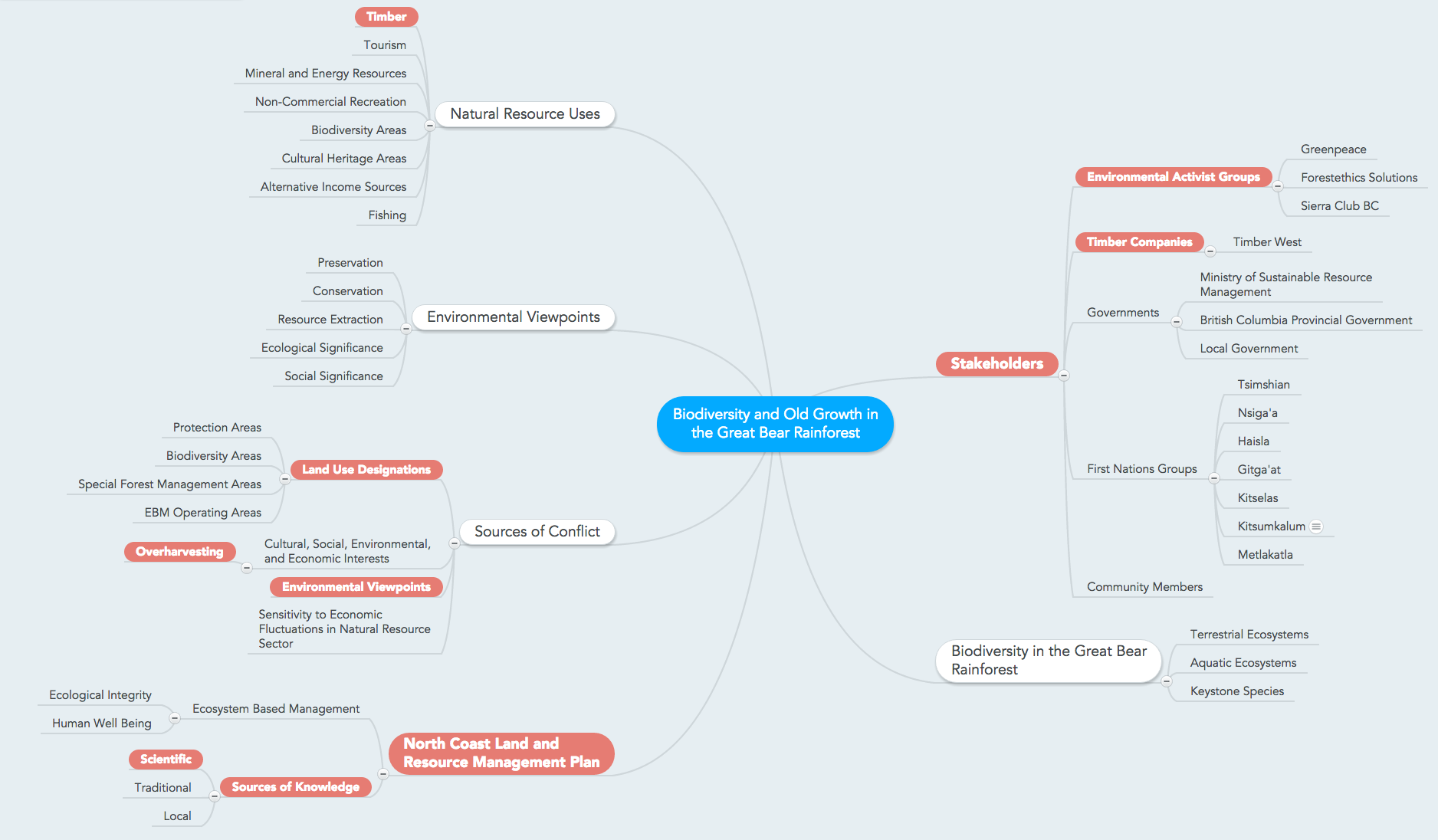

The Great Bear Rainforest (GBR) is an ecologically significant area covering 6.4 million hectares of coastal temperate rainforest, and represents 25% of the world’s existing ancient coastal temperate rainforest (7). Our case study examines the present framework of governance of natural resources (specifically timber) and biodiversity within this area. Historically, a top-down governmental approach to resource management governed various aspects of forest production where state and corporate licensees dominated forest production. However since the 1990s this model has been challenged by alternative approaches that consider voluntary, community, and market governance approaches (4).

Currently, governance of forests in British Columbia is primarily by the Ministry of Forests, Lands, and Natural Resource Operations, a sector of the BC provincial government responsible for the provincial Forestry Act (8). However with the creation of the Central and North Coast Land and Resource Management Plans (LRMP) (referred to collectively as the Great Bear Rainforest Agreements), there has been a shift to include multiple stakeholders in planning and governance processes. The development of the Central and North Coast LRMP was the product of numerous stakeholders and sectors, including the major forest companies, First Nations, tourism, conservation and environment, and community economic development (2).

Governance framework:

Global, international, and regional agreements:

Federal policies of forestry governance are increasingly constrained by globalization and internationalization, including regional trade agreements and activist groups (1). Institutionalization of change in governance practices may occur over time as a result of compliance with these agreements (1). Given the percentage of the world’s remaining old growth forest in BC, there has been significant international focus on BC forest practices since the 1990s. Regional trade agreement, in particular trade between the United States and Canada, has limited impact on the governance of BC forest ecosystems (1). International and regional trade agreements such as NAFTA restrict timber exports but the management of forest resources falls under provincial policy.

Federal, provincial, and local legislation:

Due in part to the emergence of sustainable forest management planning, Canadian forest policy is trans-jurisdictional and involves governance at various levels of government. The BC government has “constitutionally protected jurisdiction over the disposition of the resources on Crown lands” (Howlett, Rayner & Tollefson, 2009). At a provincial level, the Forestry Act and Forest and Range Practices Act govern the exploitation of forestry resources across the province. The government is able to issue tenure agreements of various lengths of time for Crown timber under the Forest Act to forest companies, individuals and First Nations (8).

Further provincial governance of the Great Bear Rainforest falls under the Central Coast and North Coast LRMPs (7). In a process that was led by the BC government, a planning committee made up of a range of stakeholders in the GBR created a plan that set land use objectives as amendments to the existing Forest Act. While the government remains responsible for the allocation of forestry permits, government decision makers are required to ensure that proposed licensees operate the ecological, social and economic boundaries stipulated by the plan and affected parties. These changes provide a legal framework under which the government can implement ecosystem-based management (4). Legal protection is also offered for areas within the GBR that are deemed to have significant cultural and natural values through the creation of parks and protected areas. Legislation that governs these areas includes the Protected Areas of British Columbia Act, Park Act, Ecological Reserve Act, and Environment and Land Use Act (8).

Non-statutory (informal) institutions and cultural traditions:

First Nations represent a large portion of population living in the GBR, are among the most heavily influenced stakeholders by planning decisions, and yet are often underrepresented. The National Aboriginal Forestry Association (NAFA) points out the necessity for accommodating Aboriginal cultural and traditional uses of forestry resources when considering their governance (5). To address this gap, courts have established that governments are required to consult with and accommodate the interests of First Nations who possess aboriginal rights and titles to the land (7). A two tier process was adopted in the planning process of the central coast LRMP, whereby a draft plan was submitted by a first tier table comprised of all stakeholders and then a second tier table comprised only of government and First Nations that was responsible for finalizing the plan (7).

Governance practices:

The shift from hierarchal government structures of resource governance to one that incorporates different stakeholder interests is a promising step for forest policy in the GBR. By examining the transparency, accountability, and participation of the present framework, we can assess whether ‘good governance’ manages forestry resources in the GBR (3).

Participation is a central feature of the Great Bear Rainforest Agreements. The planning process of the GBR agreements involved the input of multiple stakeholder tables whose members reached consensus agreement through interest-based negotiations. These agreements were then reviewed for approval by the BC government (7). The two-tier process that recognized the importance of First Nations in planning is a sign of good governance (7). However with respect to First Nations titles, there is no guarantee that they will be upheld even if sufficient proof is provided for a title claim. These titles are in many ways informal however, and a wide variety of infringements can be made upon them (5). The chief justice has argued that certain provincial aims including forestry, mining, and economic development can justify the infringement of aboriginal title (5). Ambiguity in the role of First Nations in governance of forest resources has already proven problematic and compromises empowered participation (3).

Accountability of governments entrusted with the protection of the forest in cases where EBM restrictions are in place, as well as of the forest companies expected to operate within the parameters of the laws and regulations has been questioned. When the Forest Practices Board reviewed harvesting practices of TimberWest, it was found that the company was cutting old growth trees supposedly under the protection of EBM. However the board cited ambiguous classification of old growth versus old forests as reasons for it being acceptable practice under the law (6). Enforcement of legislation occurs on a varying scale of state-centred hard law and market-oriented soft law (4).

Accounts of the planning process and the present legislation are readily accessible to organisations and individuals (2; 8). Yet issues surrounding unclear and ambiguous wording leave gaps in public understanding and room for interpretation by forestry companies, as shown by the rejection of First Nations title claims and the dismissal of the TimberWest investigation. The planning process for the Central Coast LRMP developed over the course of ten years, ample time for new science to emerge surrounding ecosystems and biodiversity of the region (7). Amendments have been made to the Great Bear Rainforest Agreements in 2009, 2013, and again in 2015 to reflect evolution of the plan (9).

In conclusion

Ultimately the responsibility of governance and adoption of forestry legislation in the GBR falls to the BC provincial government. While they have taken steps to move from government to governance, they should be viewed as movement towards greater transparency and consistency rather than a solution (4; 10). Ambiguities in legislation, as well as a lack of accountability enforcement have been identified as major failures of governance that need to be addressed. Additionally, recommendations of stakeholder tables should be incorporated into finalized legislation in a more meaningful and empowering way.

References:

(1) Bernstein, S., & Cashore, B. (2000). Globalization, four paths of internationalization and domestic policy change: The case of EcoForestry in british columbia, canada.Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue Canadienne De Science Politique, 33(1), 67-99. doi:10.1017/S0008423900000044

(2) British Columbia Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management. (2005) North Coast Land and Resource Management Plan: Final Recommendations. Retrieved fromhttps://www.for.gov.bc.ca/tasb/slrp/lrmp/nanaimo/ncoast/docs/NCLRMP_Final_Recommendations_feb_2_2005.pdf

(3) Darby, S. (2010). Natural resource governance: new frontiers in transparency and accountability. Retrieved from Transparency and Accountability Initiative website: http://transparencyinitiative.theideabureau.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/natural_resources_final1.pdf

(4) Howlett, M., Rayner, J., & Tollefson, C. (2009). From government to governance in forest planning? Lessons from the case of the British Columbia Great Bear Rainforest initiative. Forest Policy and Economics, 11(5), 383-391. doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2009.01.003

(5) Howlett, M., 2001. Policy venues, policy spillovers and policy change: the courts, aboriginal rights and British Columbia forest policy. In: Cashore, B., Hoberg, G., Howlett, M., Rayner, J., Wilson, J. (Eds.), In Search of Sustainability: British Columbia Forest Policy in the 1990s. University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, pp. 120–140.

(6) Hume, M. (2015, July 27). Report chides TimberWest over old trees in the Great Bear Rainforest. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/british-columbia/report-chides-timberwest-over-old-trees-in-the-great-bear-rainforest/article25716089/

(7) McGee, G., Cullen, A., & Gunton, T. (2010). A new model for sustainable development: A case study of the great bear rainforest regional plan. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 12(5), 745-762. doi:10.1007/s10668-009-9222-3

(8) Province of British Columbia. (2015). Forest governance in the Province of British Columbia. Retrieved on 2 November 2015 from http://www.hspp.ca/products/Fibre/forestgovernance.pdf

(9) Strategic Land and Resource Planning. (2015). Proposed 2015 Great Bear Rainforest Order and potential biodiversity, mining and tourism areas / conservancy designations. Retrieved from https://www.for.gov.bc.ca/TASB/SLRP/GBR_BMTA_LUOR.html

(10) Teisman, G. (2000). Models for research into decision-making processes: On phases, streams and decision-making rounds. Public Administration, 78(4), 937-956. doi:10.1111/1467-9299.00238