Started in 2011, the Singapore Memory Project (SMP) is an online national archive that aims to collect and document memories related to Singapore from “individual[s]… organisations, associations, companies and groups”. As of this writing, the SMP has gathered over a million memories. The web portal not only encourages Singaporeans of “all walks of life” to contribute to the national memory, but accepts contributions from visitors so long that their experience is related to Singapore. By allowing a wide variety of contributors, the website aims to foster an inclusivity and construct a national narrative that is more complete and whole. However, archival scholar Rodney G.S Carter reminds us that it is impossible for an archive to cover all aspects of society (216) – memories are fundamentally personal and in preserving all of it, contradictions and conflicts arise (220). As much as the SMP wishes to be as inclusive as possible, its “power to exclude remains a fundamental aspect of the archive” (Carter 216).

Started in 2011, the Singapore Memory Project (SMP) is an online national archive that aims to collect and document memories related to Singapore from “individual[s]… organisations, associations, companies and groups”. As of this writing, the SMP has gathered over a million memories. The web portal not only encourages Singaporeans of “all walks of life” to contribute to the national memory, but accepts contributions from visitors so long that their experience is related to Singapore. By allowing a wide variety of contributors, the website aims to foster an inclusivity and construct a national narrative that is more complete and whole. However, archival scholar Rodney G.S Carter reminds us that it is impossible for an archive to cover all aspects of society (216) – memories are fundamentally personal and in preserving all of it, contradictions and conflicts arise (220). As much as the SMP wishes to be as inclusive as possible, its “power to exclude remains a fundamental aspect of the archive” (Carter 216).

Attempts to Include

Browsing the website, it appears that the SMP has done significant work to be as inclusive as possible: not only is anyone able to upload memories, but the process is also simplified by linking personal memory accounts to existing Google, Facebook, Windows Live ID accounts, etc. All content is published in the portal immediately, as the SMP “aim[s] to be as open as possible”. Furthermore, SMP partners and volunteers, acting as pseudo-archivists, interview, write, document, translate, and transcribe to collect memories from individuals and events which may otherwise have difficulty in having their voices represented in the archives. While these efforts are commendable, the work done by these archivists remain restricted by the “interpretive frameworks” (Berger 17): existing narratives that stories tend to conform to. Thus, the increased accessibility merely makes way for more stories that fit an existing dominant narrative. A quick search for “Barisan Sosialis”, the main opposition party of the 1960s, brings up a mere 55 results (most of which are not, in fact, related to the political party), while a search for “PAP” (short for “People’s Action Party”), the ruling party, turns up close to 3000 results. While one might argue that it is because the PAP has been dominating the political scene that more memories of it exist, while the Barisan Sosialis’ dissolution in 1988 is a good reason for the lack of memories of it. Yet, I would argue that it is precisely because of the SMP’s creation and existence in this decade, where the dominant narrative is that of the PAP’s success, that the SMP creates a biased and incomplete narrative. One can easily imagine an archive that existed in the 1960s that offers a more balanced perspective of the Barisan Sosialis and the PAP. By increasing accessibility of the archive in today’s Singapore, the SMP is simply reinforcing the dominant narrative that has existed for decades rather than offering a more complete look into Singapore’s past.

Thus, rather than simply increasing accessibility, Carter suggests that to create a more complete archive, archivists must actively seek out and recognise gaps and silences within the archive (217). Only then, can archivists make the effort to either bring attention to the gaps, invite the marginalised to fill in these gaps, or respect the maintenance of silence by the marginalised (Carter 217). In the case of Singapore and the SMP, one such gap belongs to the vibrant political scene of the 1960s, in particular the opposition parties of the time, who have been left out in the national memory that has often reiterated the PAP’s dominance.

Power to Exclude

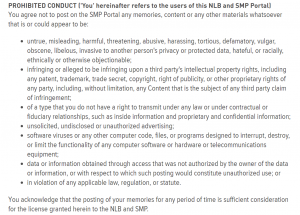

In my earlier example, I have demonstrated the SMP’s implicit power to exclude in its role as an archive. Yet, at the same time, it possesses a very explicit power to exclude within its terms and conditions page:

Of the long list of prohibited conduct, I draw attention to the first and last restrictions:

“untrue, misleading, harmful, threatening, abusive, harassing, tortious, defamatory, vulgar, obscene, libelous, invasive to another person’s privacy or protected data, hateful, or racially, ethnically or otherwise objectionable;”

“in violation of any applicable law, regulation, or statute.”

Indeed, one can safely assume that these conditions are in place to prevent the uploading of offensive or harmful materials. In particular, the protection from offensive “racially” and “ethnically” offensive materials is backed by the Sedition Act to prevent racial disharmony in a proudly multiracial, multi-ethnic, and multicultural country. However, a quick look at the government’s history of using the law as a tool of censorship tells a very different story of purposeful exclusion for political reasons. For instance, founding father Lee Kuan Yew has, on more than one occasion, sued journalists and opposition politicians for defamatory articles that suggested that nepotism and court manipulation were at play for the ruling party’s dominance throughout the years. The Newspaper and Printing Presses Act also limits the political critique that can be published in local media, while the Sedition Act and Official Secrets Act further censors media that may threaten security or racial relations. Even without citing these laws, government bodies have had a tendency to censor or discourage alternative political commentary, such as the National Arts Council (NAC) withdrawing funding for Sonny Liew’s comic The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye after discovering its sympathetic portrayal of opposition parties in Singapore’s formative years. Yet, in its statement, the NAC merely declared that its withdrawal was due to “sensitive content, depicted in visual or text”, without mentioning clearly how it violates existing laws or policies.

Returning to the SMP’s limitations, we see how it might be challenging or even dangerous to upload memories that do not stay within, or are at the edge of, the boundaries set by the many laws that prevent alternative discourse. The power to exclude in the archive is not only active, in that it reserves the right to remove content that may not fit in the national discourse, but also passive, as Singapore’s long history of heavy-handed censorship has given its citizens a good reason to fear the long arm of the law.

Final Thoughts

The work of archival studies by Carter has helped me better understand and interpret the limitations of archives that may, on the surface, seem objective, but in reality, possess immense ability to exclude stories that do not conform to the master narrative. This quick study of the SMP has given me more insight into how my country has attempted to reinforce its dominant narrative through a “renewed and seemingly more inclusive version and performance of The Singapore Story” (Tan 244).

Works Cited

Berger, Stefan. “The Role of National Archives in Constructing National Master Narratives in Europe.” Archival Science, vol. 13, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1–22. doi:10.1007/s10502-012-9188-z.

Carter, Rodney G. S. “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence.” Archivaria, no. 61, 2006, pp. 215-233. Archivaria, http://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/12541/13687. Accessed 25 Feb. 2017.

Tan, Kenneth Paul. “Choosing What to Remember in Neoliberal Singapore: The Singapore Story, State Censorship and State-Sponsored Nostalgia.” Asian Studies Review, vol. 40, no. 2, Feb. 2016, pp. 231–249. doi:10.1080/10357823.2016.1158779.