An analysis of The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye‘s contributions to Singapore’s master narrative

Over this past school year, and across various courses in the Co-ordinated Arts Programme (CAP), the term “hegemony” has been repeatedly mentioned. Hegemony – the dominance of one group over another – is a concept that pervades various other broad topics that we have encountered in our classes: in history, a narrative is constructed by dominant groups that tends to neglect marginalised voices; in identity, powerful groups marginalise and silence certain identities, expecting them to conform to standards of the dominant in return; in memory, dominant groups decide what gets remembered, and what is worth remembering, even in seemingly objective situations such as archives.

At the intersection of history, identity, and memory lies the significant issue of national memory, which too tends to conform to a hegemonic narrative as dominant groups shape and tell a nation’s history (Belsey 111). This “master narrative” (Thijs 60) told by people in power allows them to define a nation’s history and culture, in turn shaping their citizen’s national identity and silencing alternative perspectives of history. Yet, just as hegemonic frameworks constrain how national memories and master narratives are told, so too does alternative literature, such as comics, have the potential to disrupt these frameworks and make their own contributions to national memory. I would also like to focus my study specifically on the accommodation of audience in said literature when thinking about national memory, and how what the author chooses to explain and similarly, leave unexplained, tells us more about how national memory is constructed.

The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye

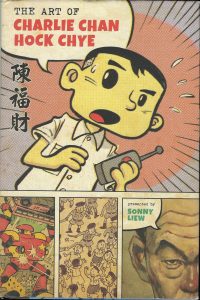

In this final ASTU blog post, it seems fitting for me to return to the research site of my final paper – The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye by Sonny Liew – as a case study for how literature has the potential to disrupt hegemonic frameworks. The Art of is a metafictional comic biography about Charlie Chan, a fictional Singaporean comic artist who grows up alongside Singapore’s national development and draws comics that serve as socio-political commentary of Singapore’s history. Through comical techniques, Liew invites readers to think about how Singapore’s master narrative is shaped, for what purpose, and by who. In turn, Liew challenges readers to rethink their position as an audience that is easily manipulated, and to consider alternative perspectives of history.

Source: Sonny Liew, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, Pantheon, 2015

What then, first and foremost, is the dominant or hegemonic perspective of Singapore’s history – Singapore’s “master narrative”? Kenneth Paul Tan calls it “The Singapore Story” (236), which perpetuates a narrative of progress, as the dominant story is that of how Singapore developed from a “sleepy fishing village” to the global hub it is today. While there is no denying the progress that Singapore has indeed made in its short time as a nation despite its small size, the narrative is reinforced by and serves the ruling party – people in positions of power. In emphasising Singapore’s development as positive, the ruling party retains control and justifies its methods of ruling the state as it points to its track record of Singapore’s progress under its rule.

Counter-Narrative Efforts by Accommodating Audience

The most important quality of The Art of that has allowed it to craft a counter-narrative to Singapore’s master narrative, I believe, is its mass appeal. In Singapore, The Art of has received much popularity, ironically due to the widespread news of how the National Arts Council withdrew funding for it after citing its “sensitive content”. Very much like the Streisand effect, this only gave it more attention both in Singapore and in the international sphere. More significantly, it is important to note the popularity of The Art of due to how The Singapore Story is often lenient towards “alternative political expression” only because they are seen as high-brow elitist culture that have little effect on the masses (Tan 237); The Art of transcends that and creates a counter-narrative for the general public. As a comic, it is also easily accessible and readable for a wide audience.

How then, apart from drawing a wide audience, does The Art of craft its counter-narrative by thinking about audience? First, Liew accommodates readers both familiar and unfamiliar with Singapore’s history by providing detailed explanations and endnotes throughout his book. Liew also invokes multiple voices that help provide commentary on the work that we are reading, and its significance. These voices include those of both Charlie and Liew himself, who appear as avatars that speak directly to the audience with the purpose of providing basic context, to directly emphasising the importance of a particular event or work. For instance, in Charlie’s comic strips “Bukit Chapalang” – satire of the Singapore’s history leading up to its independence, Liew adds additional notes underneath each strip to provide the historical background that the strip is parodying (Liew 186-190). Later, Liew himself is cartoonised and too explains the necessary context to an unnamed child that presumably represents the reader (Liew 194-197). In doing so, Liew accommodates readers with limited knowledge of Singapore’s history, which includes not only international readers, but also local readers who may not have been exposed to the alternative perspective of history.

Source: Sonny Liew, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, Pantheon, 2015, p. 190

Source: Sonny Liew, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, Pantheon, 2015, p. 196

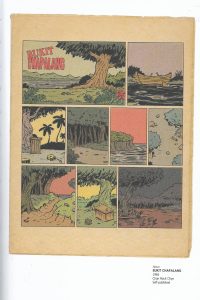

In a later strip of “Bukit Chapalang” that depicted the race riots of 1964, Liew inverts the order of commentary, with his and Charlie’s avatar providing the context before showing the comic strip. In doing so, Liew sets up the emotional weight of the scene before introducing it, further emphasising the tragedy of the incident. Liew, speaking through Charlie, says “it didn’t seem like a situation to be made light of … not the kind of thing to joke about”, and in the strip of “Bukit Chapalang”, we see what Liew calls “a strip featuring snapshots of desolate “Bukit Chapalang” locales, emptied of its characters” (Liew 198-199), which is further void of any dialogue or captions. Scott McCloud, in Understanding Comics, identifies this type of transition as “aspect-to-aspect transitions” that “establish a mood or a sense of place, [where] time seems to stand still in these quiet contemplative combinations” (79). Here, a sombre mood is established by the lack of characters or text, with context being provided by an external voice rather than from within the strip itself. By doing so, Liew challenges how the master narrative has portrayed Singapore’s rule under the ruling party as positive and impressive, instead reminding the reader that tragic incidents have happened in the past under said rule, and to remember the darker sides of the nation’s history.

Source: Sonny Liew, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, Pantheon, 2015, p. 198

Source: Sonny Liew, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, Pantheon, 2015, p. 199

Final Thoughts

The Art of has shown us that alternative literature has a place to contribute to national memory by thinking about its audience – from attracting a wide audience to accommodating different readers to setting the mood for said audience. Apart from a scholarly perspective that has found Liew’s work particularly interesting, I also hold his work and my work close to my heart as this research site has allowed me to apply research skills and concepts from class to an interest of mine. Reflecting on the lessons I’ve learnt this year, the biggest takeaway, especially with regards to the concepts of hegemony and audience, would be to challenge what we are reading and consuming. For everything that is said, there remains something unsaid and silenced. We may never receive – nor be able to complete – the full story, but by looking between the cracks and reading between the lines for voices of the marginalised and censored, we can get just a little bit closer.

Works Cited

Belsey, Catherine. “Reading Cultural History.” Reading the Past: Literature and History, edited by Tamsin Spargo. Palgrave, 2000, pp. 103-17.

Liew, Sonny. The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye. Pantheon, 2015.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics. HarperPerennial, 1994.

Tan, Kenneth Paul. “Choosing What to Remember in Neoliberal Singapore: The Singapore Story, State Censorship and State-Sponsored Nostalgia.” Asian Studies Review, vol. 40, no. 2, Feb. 2016, pp. 231–249. doi:10.1080/10357823.2016.1158779.

Thijs, Krijin. “The Metaphor of the Master: “Narrative Hierarchy” in National Historical Cultures in Europe.” The Contested Nation: Ethnicity, Class, Religion and Gender in National Histories, edited by Stefan Berger and Chris Lorenz. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, pp. 60-74.