Category Archives: Uncategorized

The CAP Conference: Public Spaces, Social Movements and the Internet

During the CAP Conference, I was amazed by the wide range of creative work presented by my peers in the Global citizens stream and the other CAP streams. Watching their presentations and their interdisciplinary contributions to knowledge from lenses as varied as Sociology, Political Science, Psychology and Geography proved to me just how much we had all achieved in our time as CAP students. Although I was impressed by the showcase work in the conference, I really enjoyed watching the panel presentation “Occupying Media: Public Space and Arendt” by the PPE students Tess Cohen, Marina Tischenko and Gareth Chevreau. In particular, I thought that Marina’s presentation on the Occupy movement in Vancouver brought up many of the topics we had discussed in the Global Citizens stream. By comparing the use of public spaces in Ancient Greece with that in the 2011 Vancouver Occupy movement, Marino showed just how much the character of public spaces for political discourse has evolved. According to Marina’s research, while public spaces in Ancient Greek used to confine protests and political discourse within specific locations (usually in buildings), now public spaces are increasingly porous, allowing rapid shifts of individuals across space. Therefore, the disruption of a particular area by officials does not necessarily shut down the entire movement, as individuals are now able to congregate in a vast range of settings- in streets, parks, and other open spaces where their voices can be heard.

Yet, as Gareth Chevreau points out in his presentation, rather than being restricted to physical localities, social movements are now increasingly coordinated in cyberspace, particularly in social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter. I thought that this tied in nicely with our discussions in Sociology about how information technologies are increasingly facilitating connections and coordination within social movements, while also producing new ‘virtual’ social movements. In our digital age society, these “spaces of flows” (to use sociologist Manuel Castells’ term) are becoming the main platforms to receive up to date information about the development of the protests, to freely express opinions about the movements and to mobilize large masses of people.

Nowhere has it become more clear to me than in (1) my Facebook news feed, and (2) the Facebook public pages on the Venezuelan protests. Given the turmoil in Venezuela at the moment, my family members and friends in Facebook have been frantically posting links to news articles and Youtube videos- mostly videos showcasing the repressive and violent actions of the government, but also quite a couple of hilarious videos mocking the president. Meanwhile, Facebook public pages such as “SOS Venezuela” have been posting the times when protests are expected to take places in cities around the world and providing information about the ongoing situation in Venezuela. Returning back to my earlier point, I think its significant to note how these budding virtual networks are influencing how individuals come together into collectives to advocate for social change. However, I think that it is best to see these technological systems not as separate from physical urban spaces, but as intersecting with them so that they collectively contribute to the creation of socio-spatial meanings and provide the grounds for social movements to take place.

Seeing as this is my last ASTU blog post, I just wanted to end by thanking everyone in our class, you guys have made this year a great one! (:

Filed under Uncategorized

Faking it: Diamond Grill vs. Cockeyed

Following our in-class discussion of “faking it” in the context of Ryan Knighton’s memoir Cockeyed, as well as our more extensive exploration of the concept earlier in the term as it relates to Fred Wah’s biotext Diamond Grill, I thought that it could be useful to compare the ways in which the idea of identity performances or “faking it” is approached in these two drastically different autobiographical texts. Although I seek to compare these texts, particular emphasis will be placed on “faking it” in Cockeyed.

While in Diamond Grill, faking it means passing as a privileged member of the dominant racial group in spite of partially being a member of a minority group, in Cockeyed, faking it takes a different meaning: it refers to the attempt to superficially appear ‘normal’ despite having a physical disability. In Diamond Grill, given that Wah is only one-eight Chinese, his external appearance does not disclose any details about his mixed racial identity, allowing him to be “camouflaged by a safety net of class and colourlessness” (Wah 138). Similarly, in Cockeyed, Knighton’s partial sightedness at the onset of his eye condition enables him to pass as “normal” and “sighted”, allowing him to reap the social benefits and privilege of being associated with the hegemonic normative culture. However, in Cockeyed, it seems that there is a more active attempt to be seen and accepted as part of the normative group. For instance, as Knighton starts to become familiarized with the differential social treatment of the disabled and the potential disadvantages of being associated with the special needs community, his decision-making comes to be shaped by his desire to disguise his identity as a blind man. For instance, as explored in the chapter “At Home with Punk”, Knighton begins to visit Vancouver night-clubs more often, seeing them as the ideal scenes for him. Here, he is able to blend in seamlessly (Knighton 51), as the movements common to individuals with eyesight deficiency, including toppling over, stumbling and falling are seen as normal in nightclubs. Therefore, as Knighton confesses, the culture “camouflage[d] [his] inability to cooperate with bodies around [him]” (Knighton 64), allowing him to fake a degree of normalcy.

Nevertheless, as Knighton succumbs deeper into his blindness, it seems that the rift between the worlds of normalcy and disability also starts to grow. Seeing the sphere of normalcy receding further into the distance, threatening to leave him at the periphery, he gradually finds himself resorting to a series of other behavioral patterns in order to retain his position as a member of the sighted community. Indeed, Knighton continually takes potentially life-threatening measures in order to preserve his façade of normalcy. For instance, even after receiving instruction on how to properly use the cane, Knighton admits that it takes “several weeks” (Knighton 69) before he actually begins to use it, consciously leaving the device in his bag in order to camouflage his eye condition.

What is particularly significant here is the degree to which he endangers his life to be labeled and accepted as ‘normal’, or part of the dominant culture. The fact that he takes such measures to avoid being categorized as disabled not only indicates his shame towards his disability, but also highlights an internalized social stigma towards people with disabilities. As we have briefly discussed in class, particularly following our reading of Couser’s “Rhetoric and Self-Representation in Disability Memoir” Knighton’s stigma towards his blindness at the initial stages of his eye condition is the product of the dehumanizing frames utilized to depict disabled communities. In emphasizing their deviance, malignancy and monstrosity, the public and official discourses (and of course the dominant rhetorics in disability memoirs identified by Couser) solidify confining stereotypes of people with disabilities as inferior individuals who are incapable of interacting with the larger society. Although they might try to resist these labels, soon these individuals begin to evaluate and dissect themselves from normative eyes and recognize themselves as ‘Other’. These stereotypes therefore often become foundational to the self-perception of individuals with disabilities, which has undoubtedly detrimental impacts on their self-esteem.

Filed under Uncategorized

Exploring Research Topic Options: Of Digital Storytelling and Human Rights Protests

As I was searching for ideas for my final paper, I was originally drawn to disability memoir Cockeyed and perhaps considering the life narrative as an attempt to negotiate entrenched power dynamics between disability groups and the dominant groups. As argued by Couser, disability life narratives enable traditionally marginalized groups to re-gain some control over their own representation and thus to contribute to the construction of their collective identity (31).Therefore, I considered perhaps exploring the means through which Cockeyed acts as a counter-narrative to the hegemonic representations of the blind.

However, given the inconceivable violence of protests in Venezuela over the past two weeks, in addition to the frequency with which stories, videos and articles have appeared in my Facebook news feed, I couldn’t help but begin to wonder some of the possible lens or angles that I could use to explore the crisis in my term paper. Having recently read Jiwani and Young’s article Missing and Murdered Women: Reproducing Marginality in News Discourse on media representation of vulnerable subjects, I thought that one way I could approach the paper could be by researching the Western media’s representation of Venezuela and its citizens in the recent protests (through digital media outlets e.g. CNN, BBC). I could possibly identify the dominant frames and counter-frames in the articles, and then proceed to critically assess some of the potential geo-political meanings and implications underlying the discourse. What are the major frames or tropes used to represent the country? As I browsed through the articles from CNN I kept noticing that inflation, corruption, state violence, shortages continuously emerged in the introductory remarks, constructing an image of a crippled and desperate nation struggling to cope with an unstable government and an ever-increasing burden of an financial and socio-economic troubles. Yet in the series of articles since February 12th, are the voices of Venezuelan citizens heard, or are they silenced and eclipsed by the voices of Western political analysts and journalists?

Nevertheless, after discussing my research topic with Professor McNeill, I realized that since the resistance movement by the opposition group seems to be in full swing and shows no sign of faltering, it is likely that the media will continue to cover stories in the region. Therefore, the data may not provide a holistic view on the Western media representation of the Venezuelan crisis.

With this in mind, I have decided to alter my research topic to explore the functions of digital storytelling in Youtube videos of human rights protests. Specifically, I am interested exploring how storytelling of protests through social media can contribute to dismantling and destabilizing the embedded power dynamics that transfer authority to media institutions, by offering an alternative “insight” and thus feeding in to the construction of the collective national identity. What are recurring patterns that emerge in Youtube videos by individuals explaining human rights and resistance movements?

As part of their study of life narratives in the field of human rights, Schaffer and Smith contend that autobiographical accounts relating to human rights are often products of particular kairotic moments of transformation (1) and often arise due to local movements. Such movements generate “occasions for witnessing to human rights abuse” (4) and for collective remembrance of the past, offering space for the voices of those at the margins to be heard. This is further substantiated by Poletti in her article, Coaxing an intimate public: Life narratives, where she argues that since digital stories focus on bringing in the voices of marginalized individuals, they offer an “experience of inclusion and community building” as well as “empowerment”, diversifying the voices in the public sphere. I considered perhaps looking at the following video: “What’s happening in Venezuela in a nutshell? (English version)”. However, since I want to be able to capture a series of recurring patterns in order to synthesize an argument on the key strategies harnessed by these digital narratives and their potential functions, I will also browse Youtube in search of other videos on renowned protests in Syria, and in Kiev, Ukraine.

Filed under Uncategorized

The Archives & TRC: Strategically maneuvering space in the promotion of national interests

Following our study of geopolitics in Geography, one of the key points that emerged for me was how the images of places and spaces can be strategically manipulated in order to advance the interests of certain privileged groups. According to the professor Joanne P. Sharpe, in order get at the root of geopolitics, or the study of the political and strategic significance of geography, it is vital to grasp the concept of critical geopolitics, which understands geography to be a “’discourse’, created by powerful individuals and groups and used as a map or script with which to understand the world.” (Sharp 39). This concept suggests that through a mixture of coercive and non-coercive means, institutions like international corporations, media industries and the state attach concepts and ideologies to places, thus reducing the complex social texture into simplistic packages. In this way, we may come associate the Soviet Union with communism, while we may link the USA to capitalism, freedom, democracy and humanitarianism. These images and the testimonies that often construct them are significant, because, as are products of a specific social and cultural milieu (Whitlock 79), or kairos, they are marked by the political and strategic interests of that period in history.

Yet the scales for observing these image-building processes at work are not just restricted to the national geographic scales; rather, we could argue that they are manifested at the micro-levels, as in the design and layout of various archival documents at UBC’S Rare Books and Special collections, or in the spatial organization of the TRC exhibition at the Museum of Anthropology. For instance, as I hunted for patterns in the Yip Sand Family archives in the Chung Collection for my Archives Analysis, I was struck by the spatial arrangement and organization of Chinese and English characters in the Yip Sang Family’s exercise books. While the characters commonly associated with the English written culture were centralized in the page, Chinese characters were almost invariably scribbled on the outer margins. Given the enormous agency of archives in both shaping a collective memory and in molding cultural identity (Carter 220), such visible forms of marginalization could potentially serve to consolidate not just Western supremacy in written culture, but may also work to naturalize the place of Chinese communities at the periphery of the Canadian society.

Now turning to the TRC exhibition at MOA, the architecture of the exhibition itself is intended to provide comprehensive and fleshed out story of the Residential schools. As such, the exhibition commences at the far end by presenting the intended functions of the residential schools (as seen in speeches by politicians and educators, magnified against photographs of ruined classrooms) then gains momentum as it presents us with individual accounts of experiences at the residential schools, and finally with the series of apologies that have been offered to the Aboriginal communities to date. Each specific section enables voices of diverse groups of individuals to be heard, with the victims being given a central, primary role in the story-telling process. Nevertheless, the audience themselves are not excluded from the process: the table found at the heart of the exhibition gives them the opportunity to be active witnesses, contributing their thoughts to memory books and boxes that may come to form part of the nation’s history and identity.

Carter, Rodney G.S. “Of Things Said and Unsaid: Power, Archival Silences, and Power in Silence”. Archivaria. 61. (2006): 215-233. Web. Jan 10. 2014.

Whitlock, Gillian. “Soft Weapons: Autobiography in Transit”. University of Chicago Press. (2007): 77-80. Web. Feb 5. 2014.

Filed under Uncategorized

Racialization: a categorical system or a process?

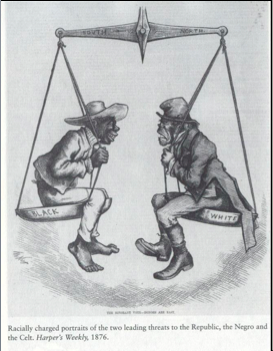

For a long time, the abstract concept of race has been one that has remained largely enigmatic for me. Given that it is a tabooed subject of conversation in a supposedly “color blind” multicultural society that is impartial to visible physical differences, I had not sought to explore the controversial topic further beyond our academic study of racial theory in Sociology. However, during term 1, I had the opportunity to take an Urban Studies 200 course, which primarily undertook critical perspectives in its approach to the cities and introduced us to a multiplicity of theoretical ideologies relating to urban regions. As part of one of the lectures on racial identity in the city, professor Wyly brought up that race and ethnicity should be seen as historical and geographical “processes”: it is inappropriate and outdated to see them as categorical systems. Initially, I recognized the validity of this perspective, as it is undoubtedly the case that how we perceive race has shifted over time. For example, as illustrated by the 1876 issue of Harper’s Weekly, in the 1870s Celts and the Irish were not understood to be white in the United States; however, now we can definitely “classify” them under this heading.

Nevertheless, we cannot completely disregard the view of race as a categorical system, for it remains forcefully present within our society. Indeed, in his book “Race”, Jake Kosek (2009) identified race as a social system that differentiates and classifies individuals into fixed categorical groups by identifying innate physical similarities and inferring “immutable” internal characteristics (Kosek 615). From our youth, we are socialized to attachspecific values and norms to various ethnic and racial groups. As we internalize the views of those with whom we interact including our parents, teachers and friends, we ultimately come to generate minimal, highly fragmented and stereotypical images of each race. These images act as the foundation to cultural understanding, further building on the experiences that we have had with a few membersof those “groups”.

As mentioned by the participants of the documentary Between: Living in the Hyphen, despite the fact that there is more widespread cultural acceptance in the current age characterized by diversity, multiculturalism and globalization, there is also a marked persistence to divide and segregate people into factions on the basis of physical traits and cultural backgrounds. These racial distinctions are reinforced, advanced and perpetuated informally and intentionally- but they may also be done through official documentation: including customs forms and in the national census of Canada.

Personally, each time that I fill out these forms, I am reminded of my Latino heritage, my inalienable belonging to this group, as well as the expectations of belonging to that community, never mind that I haven’t lived in the country in the past 7 years and no longer see myself as possessing many of the distinguishing cultural values and characteristics associated with Latino culture. While such details of the legal infrastructure are essentially included to monitor and eliminate racial discrimination and not with the purpose of enhancing racial barriers, they remind us that we live in an “either/or” world, as suggested by the individuals in the documentary. It is assumed that we if we look a particular way or have a certain surname, we must descend from a common and uniform ancestry. With the exception of the tiny “Other” section in these official forms, no space is made for inbetweenness or to account for individuals with “blended” origins. The participants in the documentary, in addition to Fred Wah’s family tree, are a testament to the fact that with each generation, racial identifications are becoming more convoluted, signaling the need to alter our perspectives on race. Returning back to the original question, perhaps it is necessary to see race as an evolving process…yet could this ever exterminate our view of race as an axis of difference? Is this even an achievable goal?

Works Cited

Jake Kosek (2009). “Race.” In Derek Gregory, Ron Johnston, Geraldine Pratt, Michael J. Watts, and Sarah Whatmore, eds., The Dictionary of Human Geography, Fifth Edition. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Filed under Uncategorized

About the agency and unpredictability of life narratives in a global literary market: Loung Ung’s First they Killed My Father

Seeing as we are approaching the end of the Winter term, I thought that it fitting to do a final post that delves into one of the most valuable insights I gained from the ASTU 100A course. As I am sure other students will agree, an idea that has been of outmost significance in understanding our work with life narratives has been Whitlock’s notion life narratives as “soft weapons”; that is, influential yet highly malleable tools that have the potential to be manipulated to serve the purposes of dominant entities (for, prior to the course, I had never considered their potential to become such potent forces in shaping discourse and social action.) We have touched upon “their political agency” at various instances during the course, emerging yet again in discussion about Chute’s article on Persepolis and the idea that life narratives can act as “lightning rods”. to human rights discourse and engender “social action” in blogs as they can create universal identifications. In doing so, they can consequently draw an empathic and emotional response from readerships. Despite spatial and temporal distance from these autobiographical subjects, we are able to feel certain closeness due to the universality of their experiences, particularly as they are often drawn from the lens of a young child, one whose simplicity of early experiences transcends cultural barriers. Indeed, such a case is apparent in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis: where Satrapi’s young perspective is embodied by a child version of herself, from whose naïve eyes we observe an oppressive and violent regime. However, following one of my last blog posts, where I included the article: “Isabel Allende, Loung Ung and the Power of Memoirs”, I’d like to delve further into this last memoir’s power: why is it that Loung Ung’s narrative First They Killed My Father has sparked such a profound emotional response from Western readerships? Are narratives really as invincible and powerful as they often seem to be?

First they Killed My father is a memoir written by Loung Ung, where she recounts her experiences in the Pol Pot regime as a survivor of the Khmer Rouge years. Hers is a traumatic tale of estrangement, separation, and tiredness, hunger, as she is flung into the Cambodian work camps and sees her family members murdered. According to Ung, the core reason for the success of memoirs in general is that they “connect the humanity in us”. According to Ung:“we often hear about many hundred thousands killed in Darfur, and two million in Cambodia. All these big numbers. Memoirs bring it down to a family, a face… it breaks down that barrier of what is Cambodia, Vietnam, Sierra Leone, Darfur—down to a father, a mother, a brother, a sister.” So, much like other autobiographical voices in her field, in her earnest depiction of easily relatable subjects, Loung reduces those insurmountable chilling statistics of people captured and murdered into that person in the street, that guy in the supermarket, our cousin, our brothers. In short, these people are brought to life through the words, made flesh by the recounting of their experiences.

However, as commodities transferred on a global scale through circuitous movements, life narratives are subject to influence by the unpredictable forces of the marketplace and by consequence we can never truly discern audience reactions to the literary work. As Schaffer and Smith suggest, while in one location a life narrative can be the starting incentive of a human rights campaign, in another it may be the subject to substantial backlash and negative feedback. In which locations we will see these, and whether these two polar opposite reactions will be manifested, we cannot predict. Schaffer and Smith’s idea is exemplified by Loung’s memoir: on the one hand, the narrative has gained rapid success among book critic groups, launching Loung to a celebrity status as the current national spokesperson for the Campaign for a Landmine-Free World. Furthermore, it has sparked an outpouring of invitations from universities seeking to have her as a guest speaker for students about the genocide in Cambodia. On the other hand, reception from Cambodian American communities has been far from favorable: in fact, much like I, Rigoberta Menchu’s life narrative in, Loung’s autobiography has generated controversy with regards to the literary “authenticity” of her work. These communities claim that her narrative is “exaggerated, biased by her own prejudices, and peppered with untruths in an effort to profit from the atrocities of that time”, a comment that has drawn the author’s attention to the point that she herself has written an informal apology for the hurt caused by her book and provided further explanation and justification for the book. Ultimately, this shows that there are all sorts of forces working for and against life narratives: while we must recognize their substantial agency, it is also important to note that they fall vulnerable to market forces and constantly shifting sociopolitical ideologies. Most of the time, it is often impossible to predict where these forces will take them.

Filed under Uncategorized

Flickr Photostream: A Contemporary Life Narrative?

After reading my fellow classmates’ blog posts on how different apps and websites could be considered to be life narratives (particularly Margot’s blog post on the new app Bitstrips and Makoto’s blog post on Youtube) I began to become interested in how other websites could potentially be seen as autobiographical narratives. So I decided to investigate whether Flickr, an image and video hosting website, could be considered to be a life narrative. Although not as a popular as in its early days, Flickr still remains the preferred photo storage and sharing sites out there for professional photographers; for the rest of us, Instagram and Tumblr seem to have become the norm. Having recently accessed Flickr, I noticed that several changes have occurred: not only does it now allow for visitors to access the website from their Facebook and Google+ accounts (in addition to the original Yahoo! account) but its layout has undergone a complete transformation. The Flickr layout that I remember was simple, minimalistic and had a sheer white background. The new design, however, echoes the mosaic-like home page of Pinterest, with a pitch-black background and an infinite-scrolling feature. Much like the photos Tumblr, each photograph here has a feature at its bottom-left allowing visitors to like, comment or share the photographs on various virtual platforms (namely, Facebook, Pinterest, Twitter and Tumblr).

Browsing through the website, it seems that Flickr has taken more than one cue from its highly popular contemporaries. Whereas before the user’s personalized page focused solely on the photographs that the user had uploaded, it now boasts a number of new sub sections. To start off, there is the photostream section, which assembles photographs from the user and arranges them in reverse chronological order, as well as the “sets”, “favorites and “creations” sections, that remind me of Youtube’s personalized page. Given the multitude of features provided, the user has the freedom to control and directly modify the content in their page, thus they are able to mold their page to reflect specific dimensions of their personality- or rather, to showcase a self that they yearn to be. Here, the user speaks merely by virtue of the visual; the textual is most often minimal and is not read, although it provides context that is often necessary to understand the relevance and importance of a photograph. While often photographs are uploaded with no specific intention, but rather simply because they are perceived to be aesthetically pleasing after undergoing digital manipulation, (example) some users include photographs in an attempt to track momentous parts of their journey- a moment of relaxation in their life, the celebration of a birthday.

Likewise, often a series of photographs can be gathered and used to give life to marginalized subjects and minority groups, and thus create a collective life narrative. For instance the user Huzzatul Mursalin’s photostream provides insight into the daily lives of people in Dhaka, Bangladesh capturing them as they perform their daily tasks, dance in their streets, interact in the food markets. Altogether these photographs provide glimpses into fragments of their life, reflecting the daily existence of these workers and their family: while some scenes are colored with happiness and beauty, others capture them in moments of motion as they immerse themselves within their tasks. As the user binds these photographs together, he constructs his own version on the collective life narrative of the Bangladeshi people. Nevertheless, the collection of photographs is certainly limited by the fact that a selection of photographs have been actively chosen and thus they are not representative of all the lives of the Bangladeshi people.

What do you think? Do you believe that it is possible to see the website Flickr as an autobiographical practice? If so, does its architecture facilitate the presentation of personal life narratives or collective life narratives? Let me know in the comments below!

Filed under Uncategorized

Isabel Allende’s memoir Paula: Storytelling as a form of therapeutic release

Throughout our study on life narratives, one aspect that has really caught my attention is the use of life narratives as form of therapy or emotional release. We have certainly discussed the idea of life narrative as therapy in class, particularly following our presentation on the website PostSecret, as questions emerged about the likely possibility of users sending their confessional secrets in mail to the website as a way to free themselves from the weight of bearing private secrets. However, I feel that this is an area that requires further exploration: for this, I’d like to turn to the personal memoir Paula, written by the renowned Chilean novelist and memoirist Isabel Allende. For those of you unfamiliar with Allende and her work, basically, she is widely known in Latin America and abroad for her novel The House of Spirits (or “La Casa de los Espiritus”) certainly one of the most memorable books I have ever read. (There’s even a movie with Meryl Streep, Jeremy Irons and Antonio Banderas). As far as her style, I think its significant to mention that Allende tends to continually blur the boundaries between fiction and non-fiction, as she incorporates fragments of her own life into richly imaginative and meandering narratives.

As a memoir, Paula consists of a compilation of letters written by Allende as her daughter falls ill and succumbs to a “poryphia-induced coma”, as well as Allende’s own autobiographical account of her most obscure past experiences. In the article Mourning becomes Paula: The Writing Process as Therapy, writer Linda S. Maier argues that for Allende, the memoir Paula partially “serves as a creative, therapeutic release to help the author cope with personal tragedy” (Maier 237). This is certainly apparent in her interview with Marianne Schnall (7/11/08) for the article Isabel Allende, Loung Ung and the Power of Memoir, where Allende revealed that the main reason why she started the letters for Paula was that she recognized “the only way [for her] to deal with [her] grief was through writing”. Features of this “therapeutic release” are certainly evident in her inability to contain her focus as she reminisces her family life in the first chapter, fluctuating continually back and forth in time as she recounts her journey in a way that seems to exhibit characteristics of a person in the process of mourning. Following some research, I found out that the letters that eventually became part of the book were, in fact, written at the hospital as Allende witnessed her daughter’s progressive fall into her disease and subsequent comma.

To an extent, therefore, we could infer that Allende turned to storytelling as a way to heal and to come to terms with the overwhelming sense of loss and grief. Much like the protagonist of Dave Egger’s novel What is the What, Sudanese refugee Valentino Achak Deng, (who would tell his silent stories to anyone, willing to listen or not) Allende traces back her traumatic life story partially as a means to maintain her spirit, to find “strength” (Eggers 535) in her otherwise grueling and traumatic reality. Yet it is important to recognize that various motives could have played a role in her decision to produce her letters and to compile them into a memoir, and it would be an insult to the author to judge her only motive for writing the book as her need to cope with her debilitating sense of loss. Rather, one could also contend that Allende perhaps turned to storytelling to find the “sense of clarification” and “social control” (Miller and Shepherd 12) outlined by Miller and Shepherd; that is, to both find a viable way to reflect and understand her experiences in isolation and to transform her experiences into her own “prisoners”, or moments that she has control over; not vice-versa.

What do you think?

For further information about Allende, here’s a link to her TED talk “Tales of Passion“:

Works Cited

Eggers, Dave. What is the What. New York: Vintage Books, 200. Print.

Maier, L. A. “Mourning Becomes Paula: The Writing Process as Therapy for Isabel Allende” (2003). Hispania, 86(2), 237-243. Web. 16 Nov. 2013.

Filed under Uncategorized

Cultivating a sense of community in virtual websites: Six-Word Memoir, PostSecret and Facebook

A couple of weeks ago, me and a group of ASTU classmates gave a presentation about the construction of personal identity in PostSecret, a website that defines itself as an “on-going community art project”. Following our presentation, the Six-Word Memoir group, in focusing on the website Six Word Memoir, touched upon a subject that had been of great interest to me and my other classmates as we sought to decide the big issue in our presentation: community. Throughout their presentation, we were able to see how the features of the website allowed people to feel part of a larger, all-encompassing community. After the class, I was left wondering: how is it that social platforms, like PostSecret, Six-Word Memoir and Facebook generate a strongly interlinked and bonded community, or, more accurately, “engender a psychological sense of community” (Reich 1)? Do individuals truly derive a warm feeling of belonging and understanding in these seemingly distant, impersonal digital sites?

To explore how Post secret and Six-Word Memoir allow visitors to develop a sense of community, I think that it important to first provide a sound, workable definition for the abstract term “community”. I will be using the definition coined by Sociology and Urban Studies professor Barbara Phillips, whose book my Urban Studies Professor Dr. Elvin Wyly commonly draws from when contextualizing the content of our lectures. Philips sees community as “a group sharing an identity and a culture, typified by a high degree of social cohesion” (Phillips, 2010, p.167). The first part seems at odds with the cyber communities in PostSecret, Facebook and Six-Word Memoir, given that, for the most part, we can safely say that members of these communities generally do not possess exact identities or cultures . Yet, they do seem to exhibit that high degree of social cohesion captured by this definition, for members often do seem to have the sense of emotional connection and integration that I believe are characteristic of communities. In their article, Miller and Shepherd recognized that one of the key “exigences” (Miller and Shepherd 12) , that is, the main rhetorical motives for bloggers (and perhaps visitors of websites like PostSecret and Six-Word Memoir), is the need for “cultivation and validation of the self”(Miller and Shepherd 12). Recognizing this fundamental human need, many website developers including those in PostSecret, Six-Word Memoir and Facebook have provided tools to ensure that, regardless of their background or struggles, people feel included within these communities.

With regards to Facebook, I would argue that perhaps the most visible tools that enable people to feel part of a community are the Facebook Groups and Community groups, seen on the left-hand column in the Home Feed. Looking at my own news feed, you can see the Nootka group, The Fables, (my Jumpstart Learning community) and a family group titled “Gonzalez Family”. In joining these groups, Facebook allows its members to feel connected to, and integrated within, a wider group with similar interests, therefore building a sense of belonging.

Unlike Facebook, however, PostSecret has a separate branch titled PostSecret community, with a small subsection named “PostSecret Chat” where we find several categorized self-help and personal identity groups. As you can see below, the website has distinctive categories such as PostSecret Discussion, PostSecret Internative Community, in which an array of different interests and concerns are catered for by having sections such as Secrets of Mental Health, Spirituality, Soldiers’, LGBTQ, targeted at different individuals. By encouraging visitors to join in and engage with others in a conversation about specific issues, these group forums foster communication, interdependence and thus allow members to build an emotional connection with others in a technological platform. Not only are users able to interact with each other, but in the cases of mental health, they can also seek out information and provide support for other members, often even directly offering to help others in their recovery process. For instance, as I was browsing through one of the mental illness group threads, I noticed that one of the respondents tried to provide support to another participant simultaneously by giving advice and by ensuring them that, if they ever need to talk, they can always “PM” them.

Some argue that the unprecedented success of websites such as Facebook has directly influenced other websites, for in constructing their virtual communities they have “sought to incorporate [Facebook’s architectural features] into many of [their] digital platforms”. Indeed, Six-Word Memoir is a prime example of this appropriation, for (as enlightened by the Six-Word Memoir group presentation) it allows readers to comment on the memoirs and even “like” them. In addition, members are able to share the memoirs they come across with friends in other social-networking sites by virtue of a Share button, thereby enabling individuals to feel immersed within a community and helping to strengthen their social relationships through sustained interaction.

Overall, while Six-Word Memoir, Facebook and PostSecret use starkly different features to create virtual communities, they all fulfill need to belong by allowing membership to “exclusive” groups and inviting people to contribute and express their thoughts within specified parameters. Have you recognized any other distinguishing features in these sites or perhaps other sites that help to build this enigmatic sense of “community”? Is this always a positive community, in the sense that it brings benefits to users, or have you come across sites where this is not the case (e.g. Youtube and Pinterest)?

Reich, S. (2010) Adolescent’s sense of community on Myspace and Facebook: A Mixed-Methods approach. Journal of Community Psychology. Vol. 38, No. 6, 688–705. University of California, Irvine. Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).

Miller, C. Shepherd, D. Blogging as Social Action: A Genre Analysis of the Weblog. North Carolina State University

Filed under Uncategorized