Upon further reflection about the economies of life, the central theme of this blog, it has struck me that the economies of life also relate to the economies of living. In this instance by the economies of living I am referring specifically the economies of laundry, the biology of making dinner and other forms of traditionally non-waged labour. Non-waged and waged domestic labour has been a site of feminist intervention for quite some time.

In particular, feminist economic geographers have made astute contributions to the economies of gender, race and work. Gerry Pratt’s latest book Families Apart has me thinking about the trajectory of feminist economic geography and how developments in critical and socially engaged feminist theory and praxis work with the world more broadly. This book is on the lived experience of Filipino domestic workers and their children in state facilitated labour migration programs, particularly in Canada.

Riffing on the idea of feminist economic geography in relation to the world more broadly, I now digress into a discussion about how the North American Euro-centric world of laundry has changed. In my post here, I depart from an analysis of the spatial geographies of the influx of migrant work into northern countries, like to Vancouver Canada, the city where I live.

Now, perhaps laundry has changed. The role of who does laundry has certainly changed. But I am not sure laundry itself has changed. Laundry seems to keep going. Laundry is always there for someone to do.

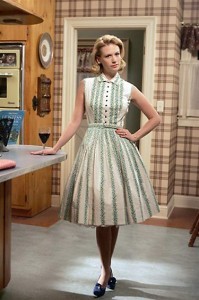

It is the everyday nature of laundry that has sparked my thoughts about how gender and geography literature, that emerged in the late 1970s and early 80s, has materialized along side international critique of the gendered terms of social reproduction. Critiques of familial social reproduction have progressed dramatically since the 1960s. The 1960s is in era idealized by the stereotypical white North American housewife (not that this housewife was ever necessarily a reality). Nevertheless in white hetero-normative cultural representation, the nostalgic image of a white apron-wearing housewife remains static as the politics of feminist economic geography and subsequent literature around gender and identity transpire to new critical heights.

There is the popularity of the show Mad Men that exemplifies this mediated apron-wearing nostalgia. While at the same time a consistent topic in news media, such as the Globe and Mail, is how women, and particularly the modern mom juggles ‘real’ work with domestic work … like laundry. According to this news media, how to strike a work-life balance has taken on a different meaning for women, who are now, according to the Globe, expected to work full time and do the laundry, or hire another woman to do the laundry. News media includes coverage of the increased participation of men in domestic labour and parenting. However, it also continues to illustrate a clear tension in terms of representations of women.

Portrayals of women as mothers are in tension in that on the one hand there are fictional media representations (Mad Men) that long for an idealized (existent?) white privileged past and on the other there is the you-can-do-it-all-rant-like coverage, statistics included, in support of the new North American mother who is ostensibly becoming a successful CEO superhero. But these conflicting representations are only a sub-point. My actual point is simply to ask, somewhat rhetorically, if and how the economies of life relate to the economies of living? And how biological (work) life, rendered as capital, has and has not changed?

One response to “The economies of laundry: How is biological (work) life rendered as capital?”