I. The Settings

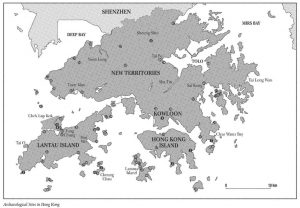

- Geography—80 miles from Canton (Guangzhou), Hong Kong Island (~30 sq mi), Kowloon Peninsula (1860; ~ 8 sq mi), New Territories (1898, ~365 sq mi) . . . cf. Greater Vancouver (~1,100 sq mi)

- Population (“guesstimates”)— 7,450 (1841) . . . 24,000 (1848) . . . 123,511 (1862) . . . 221,441 (1891) . . . 283,978 (1901)

II. (Some) Approaches to Hong Kong History

- Colonial lens

- Examples

- Geoffrey Robley Sayer, Hong Kong 1841–1862: Birth, Adolescence and Coming of Age (1937); also Hong Kong 1862–1919: Years of Discretion (1975)

- G. B. Endacott, A History of Hong Kong (1958)

- Richard Hughes, Hong Kong: Borrowed Place–Borrowed Time (1968)

- Frank Welsh, A Borrowed Place: The History of Hong Kong (1993)

- Examples

- Chinese lens – e.g., Hong Kong Chronicles (2020–)

- Localist lens – 鬱躁的城邦 : 香港民族源流史 [A national history of Hong Kong] (2015)

- City Between Worlds (2008)

III. Sources—Coming into View

- Early Chinese maps (dated to the 16th century)—Record of the Office of the Supreme Commander at Cangwu (Cangwu zong du jun men zhi) (1581 [1552]) . . . Yue da ji 粵大記 (1595)

- Early European maps (17th century–)—Dell’Arcano del Mare (1646–1648) by Robert Dudley . . . Vincenzo Maria Coronelli’s map (1695)

IV. Sources—From the Ground Up

- The Search—Pioneers (e.g., C. M. Heanley, Walter Schofield, Fr. Daniel J. Finn, Chen Kung-che 陳公哲 [1890–1961]) . . . Hong Kong Archaeological Society (1967) . . . Antiquities and Monuments Office (GIS)

- Findings—archaeological sites . . . Song-dynasty (960–1276) inscription (Fat Tong Mun 佛堂門; 1274)

V. A Littoral Zone

- Settlements—clans in the New Territories . . . Tang (Deng 鄧), Man (Wen 文), Hau (Hou 侯), Pang (Peng 彭), and Liu (Liao 廖)

- Piracy in the South China Sea—Cheung Po Tsai 張保仔 (1783–1822; 200+ ships)

VI. Clash of Empires

- Qing-dynasty (1644–1912) China and Georgian (1714–ca. 1837)/Victorian (1837–1901) England

- The “Canton System” (1750s–1842)—Macartney Embassy (1793)

- British East India Company (1600–1874; monopoly terminated in 1834)

- Tea . . .silver . . . opium

Year Silver to China (Taels) 1760s >3 million 1770s ~7.5 million 1780s ~16 million By contrast, net flow out of China: ~2 million taels each year (1820s) and ~9 million taels each year (1830s)

British sale of opium to China (chest: 130–160 pounds; source: Jonathan Spence, The Search for Modern China [2013])

Year Number of Chests 1729 200 1800 4,570 1838 > 40,000 - The First Opium War (1839–1842)

- Lin Zexu (1785–1850) and the anti-opium campaign (1839) – seizure of drugs and pipes . . . letter to Queen Victoria . . . blockade (24 March 1839) . . . 20,000 chests (~3 million pounds) confiscated and destroyed . . . “We have heard that in your honorable nation, too, the people are not permitted to smoke the drug, and that offenders in this particular expose themselves to sure punishments. . . . In order to remove the source of the evil thoroughly, would it not be better to prohibit its sale and manufacture rather than merely prohibit its consumptions?”

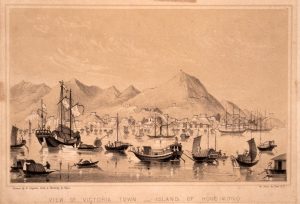

- Military response – 16 warships, 4 armed steamers . . . 4,000 troops, 3,000 tons of coal, 16,000 gallons of rum . . . June 1840 . . . the 1841 agreement . . . Henry Pottinger . . . Treaty of Nanking [Nanjing] (signed 1842; ratified 1843) . . . Hong Kong . . . treaty ports (Canton, Fuzhou, Xiamen, Ningbo, and Shanghai) . . . the “most-favored nation” clause

- The Second Opium War (1858–1860)—the Arrow Incident . . . First Convention of Peking (1860)

Discussion

Revisit the article by James Hayes. Take a closer look at the "primary" sources he cites.

- Who are his "informants"? How would you describe the genres of sources he makes use of? What are the limitations of such sources?

- More generally, what are some of the challenges historians face in trying to reconstruct the history of pre-colonial Hong Kong?

- To what extent was Hong Kong "at the edge of empires"?