Music, movies, games – the way we enjoy either of those three mediums changed massively during the past 100 years. In this blog post, I want to elaborate on the opportunities and threats that come along with the distribution of video games online as both, profitability and complications are most noticable in this medium.

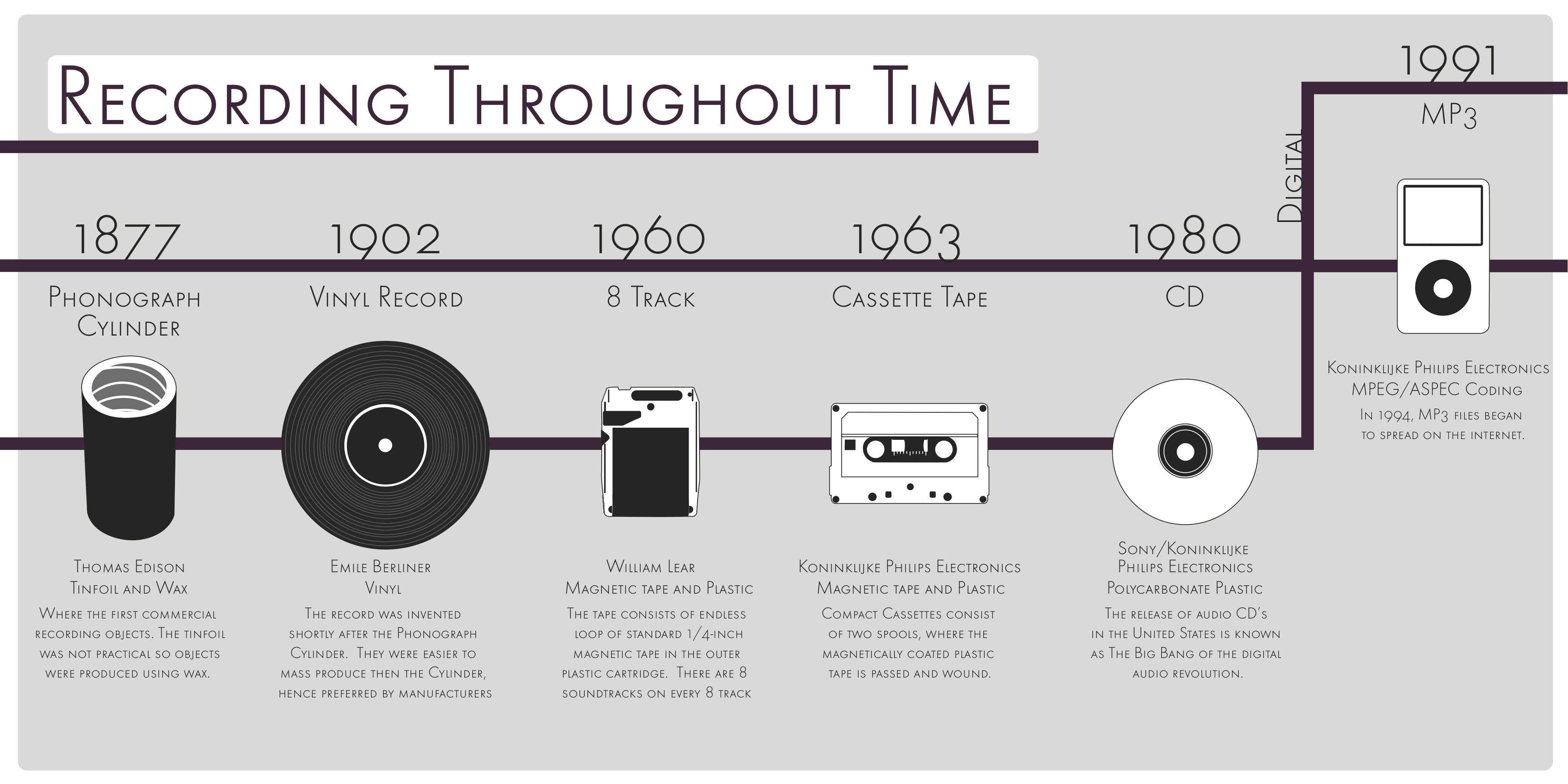

The changing distribution channels over time for music: From analogue all the way to optical and finally digical distribution.

Things did not change very much ever since video games started to be sold for home use in 1972 until the dawn of the internet. The format changed from cartridges to magnetic formats over to various forms of optical discs, but the idea was always the same: The game has to be manufactured, packaged, shipped and put up on display in a retail shop. The consumer will have to go to a shop that sells the favorite game and return home after purchasing the game.

I’m writing this as a response to the video game industry blog “NotEnoughShaders.com” who wrote a very well researched article about the rise of development costs in the industry and how it drives small companies out of business if they don’t find alternative distribution channels. The idea of downloadable game content that cuts out the traditional supply chain and is directly delivered to the customer was already introduced in the mid-90’s by Nintendo in Japan with their Satellite Download-Service, but only became common practice around 7 years ago when many major manufacturers introduced their own digital distribution methods such as the Xbox Live Marketplace (Microsoft), the PlayStation Network Store (Sony), WiiWare and Virtual Console (Nintendo) as well as the App-Store (Apple) and Steam (Valve). As technology advances and gamers expect more impressive graphics and diverse gaming experiences every year, development costs skyrocketed throughout the past decade (1).

The video game industry experienced a rapid increase in development costs over the past 10 years. This was mostly caused by the introduction of high definition technology and higher expectations in terms of storytelling and graphics.

For example, a one of the most successful games of the year 1998, Resident Evil 2 for PlayStation, had only 33 people working on it with a budget of approximately $3 million dollars (1). 2012’s Resident Evil 6 employed over 600 people and the budget most likely approached $100 million dollars – an increase of over 3300% in a bit more than 10 years.

With such increasing costs, many developers and publishers seek additional sources of income or try to optimize their supply chain. By using online distribution channels, companies such as Nintendo or Electronic Arts can not only safe all the money that was formerly spend on supplying games to retailers, but they also have better control about the distribution of their products and can aim advertisements more directly and customized to their customers tastes.

The advantages of online distribution are obvious: Download-traffic costs next to nothing to a company, therefore once the break-even is reached, variable costs are basically zero and the company earns pure profit for each additional sale. In addition, consumers can get access more directly and easier to the software they want, from everywhere in the world as long as there is internet access. This distribution method is heavily discussed in the gaming community, however, especially because of the increased empowerment of companies increases scepticism among gamers and users of this new service. A negative example of online distribution is the recent SimCity release in March this year, a game that can only be played with an established internet connection. Players were downloading the game for the full retail price, but overloaded servers prohibitied customers from using their product – and EA refused to give refunds and even threatened customers to ban their online accounts (3) (which would also delete all the customer’s previous purchases from the EA online store) if they cancel the purchase by contacting their credit card company (2).

SimCity’s technical problems caused a lot of disappointment among gamers and damaged the company’s reputation in the scene. Supposedly unrelated to this issue, EA’s CEO John Riccitiello resigned only days after the “always-online” debacle (4).

Some observers regard this recent development of increasing coercive power on paying customers as very negative, but companies will not refrain from using online distribution channels because it means almost zero variable cost for each sale. Still, the answer to the question whether companies will agree to loosen their grip on the customer with “always online software” and strict DRM or if they will continue to chain each consumer into a framework where they are exposed to the rules made by the company will remain open.

Sources

1) http://www.notenoughshaders.com/2012/07/02/the-rise-of-costs-the-fall-of-gaming/ , retrieved March 23rd

2) http://ca.news.yahoo.com/blogs/right-click/simcity-problems-bad-worse-always-online-servers-called-004720433.html , retrieved March 23rd

3) http://www.theverge.com/2013/3/7/4076104/amazon-stops-simcity-digital-orders-customer-complaints , retrieved March 23rd

4) http://business.financialpost.com/2013/03/18/electronic-arts-ceo-john-riccitiello-to-step-down-march-30/ , retrieved March 23rd

.jpg)