Our report, “Exporting extinction: How the international financial system constrains biodiverse futures” was just released. Read more below:

For decades, policymakers have known the world is in the midst of escalating ecological crises, including an unprecedented deterioration of the abundance and diversity of life on Earth. Yet international plans to halt the rapid erosion of biodiversity have consistently failed; none of the 196 government signatories to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) achieved the 20 targets to which they committed in 2010. Why do governments struggle to meet agreed-upon targets to protect and restore biodiversity?

For decades, policymakers have known the world is in the midst of escalating ecological crises, including an unprecedented deterioration of the abundance and diversity of life on Earth. Yet international plans to halt the rapid erosion of biodiversity have consistently failed; none of the 196 government signatories to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) achieved the 20 targets to which they committed in 2010. Why do governments struggle to meet agreed-upon targets to protect and restore biodiversity?

Conventional rationales for these failures tend to focus on a lack of political will, financial resources, awareness, and capacity to implement decisions. International and national biodiversity policy documents, including the 2022 Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), often assume governments have autonomy to take action on biodiversity loss; that the issue is how biodiversity policy-making remains siloed in environmental ministries, and neglected in consequential national decisions on finance, industry, and trade. This report argues that these explanations are only part of the picture.

Read in English, Spanish and French.

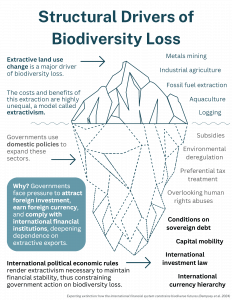

Across the planet, governments fail to meet biodiversity targets because the extraction that drives biodiversity loss continues. Extractive land use change is estimated to drive about 90 percent of biodiversity loss globally. The impacts of this land use change are also vastly uneven, often following patterns of extractivism, an economic development model based on largely unfettered resource exploitation with highly unequal distributions of benefits and impacts, both between and within the Global North and Global South. Despite these persistent conditions of extractivism, governments around the world continue to approve, subsidize, and expand the extractive developments that erode biodiversity. Domestic political agendas that privilege elite interests and extractive revenues play an important role in perpetuating these decisions. But less well-recognized is the role of structural, international political and economic pressures.

This report finds that while domestic policies support extractive sector expansion, it is the pressures of the international monetary and financial system that make extraction so necessary to maintain financial stability.

The pressures of this system act on all states, but they are experienced unequally, such that countries with the least political-economic power are often the most subject to external pressures. As a result, Global South governments, to a variety of degrees, are constrained in their ability to choose different policy pathways due to their position within the international financial and monetary system, under conditions of financial subordination. These conditions of subordination—in which many governments must contend with an economic and financial order over which they are structurally disadvantaged and politically marginalized—mean that states face exceptional pressure to remain in or expand their role as exporters of extractive commodities due to the heightened risk of financial instability.

These risks to financial stability, and their unequal application across countries, are underexplored drivers of global biodiversity loss.

Using the example of key extractive industries across 5 highly biodiverse Global South nations—Argentina, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Jamaica, and Papua New Guinea—this report explores how and why states further policy agendas that entrench and expand the industries that drive biodiversity loss. Each of these countries hosts biodiversity of global significance, but face powerful structural economic forces that incentivize the continuing destruction of biodiverse landscapes. In all the case studies, national governments recognize that their own export-oriented economic sectors are major drivers of extinction and ecological degradation. Yet these governments continue to encourage more metals mining, more industrial agriculture, and more fossil fuel development, while Indigenous Peoples, local communities, and entire nations often bear the harms of extraction with little economic benefit relative to the capital generated. While there are domestic drivers behind these policy decisions, often related to job creation and tax revenue, as well as issues of industry influence in regulatory regimes, this research reveals that the uneven structure of the global economy constrains what these Global South governments can do to address both economic development and ecological crises.

Overall, this report demonstrates how the international financial and monetary system exerts structural pressure on governments to maintain and expand these extractive sectors to maintain “investability,” to earn foreign exchange, and to comply with international financial institutions that manage economic crises. These pressures are structural in that, under this current system, acting otherwise would threaten the financial stability of many subordinated economies—stability that allows regular people to buy food and deposit their paychecks, and that allows governments to pay for key imports like technology and medicine. Consequently, there are significant conflicts between current approaches to creating financial stability and maintaining overall ecological stability. This precarious position drives subordinated states, in particular, to double down on export-oriented extractive industries such as mining, fossil fuels, and industrial agriculture, even against the mandates of their own citizens.

By constraining government policy options on extraction, the organization of the international financial system drives biodiversity loss.

Increased Global South financing, domestic policy action, and government accountability are all necessary to reduce extraction. But the research collected here suggests that those efforts will struggle to succeed without action to overhaul the unequal structure of the global financial system. Only international efforts to address these conflicting priorities, undertaken in the spirit of solidarity and collective responsibility, will be able to transform these structures and make viable the path towards ecological stability.

Read the full report in English, Spanish and French.

Why Trace Biodiversity Capital?

Conservation finance, private equity funds, land and rainforest bonds: all are attempting to “unlock” the supposedly trillions of dollars waiting around to finance the global environmental agenda. Such hoped-for funds are – in theory – meant to address the brutal realities of ecological degradation: the earth is becoming less lively, less colourful, less diverse. In what now goes under the label conservation finance, there is a growing alliance of financiers, asset managers, NGOs, and international institutions eager to find ways to make biodiversity conservation a successful and attractive financial asset. Governments and organizations around the world have started to incorporate for-profit conservation finance and impact investing ideas into their environmental, social and development policy, keen to direct private capital in the direction of conservation efforts.

This research project will help practitioners, policymakers, and scholars understand how financialization might be changing biodiversity conservation efforts and how, or if, these practices create profits. Will these new financial mechanisms succeed where previous schemes have not? If these conservation investments continue to fail in return-generation, what will happen to them? Will non-profit organizations or governments step in to save them, or, are we entering a phase of “start-up conservation” where projects will be tested, discarded and tried again, as in the venture capitalism of Silicon Valley?