1543 – 1796

The constant adaptation of a living urban heritage site

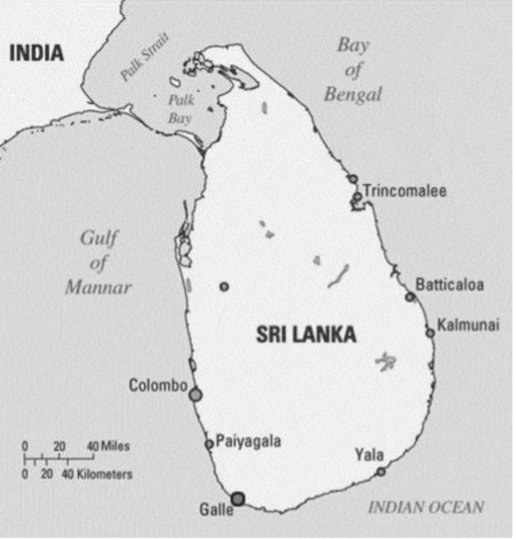

In the town of Galle on the southernmost shores of Sri Lanka sits the “Old Town of Galle and its Fortifications”, or Galle Fort colloquially, extending over 52 hectares in area. Originally built as a garrison town in the 1500’s and designated a UNESCO world heritage site in 1988, the place embodies a sense of heritage and a feeling of time and space unchanged [1]. Original components of the town, such as the ramparts and sewer system, lend themselves readily to this narrative. Upon closer interrogation of the urban fabric and architecture of the fort, however, a space that readily welcomes change and evolution emerges. As a result of the high level of interest in the site over the last 400 years, a combination of the trade and economic opportunities of the region and the architecture of the site itself, a constant influx of newfound stakeholders have interacted with the urban architecture of Galle fort to create an identify of space whose only constant is change.

Driven by the pursuit of trade opportunities and military conquests, the island nation now known as Sri Lanka was first settled by immigrants from Northern India in the fifth century BCE, forming the Sinhalese ethnic group, and subsequently by immigrants from central, eastern, and southern India during a period spanning from 4000 BCE to 1200 CE, forming the Tamils. Remnants of early native populations were for the most part absorbed into these two groups. In the early 16th century, when trade in the Indian Ocean was dominated by Eastern merchants, Portuguese explorers arrived with higher speed, military equipped vessels that quickly disrupted trade operations in the region. By establishing relations with the current rulers of the island’s kingdoms, some of whom wished to use the resources and support of the Portuguese to further their own influence, the Portuguese obtained trading concessions and built their first fort in the capital, Colombo, in 1518. Through a series of shifts in control of the local kingdoms, with the exception of the inland region of Kandy controlled by the Sinhalese, the Portuguese captured most of the land by the early 1600’s. The administrative structure of the previous Kingdom was maintained, with Portuguese officials holding the highest offices, and local offices held by Sinhalese nobility with loyalty to the Portuguese [2].

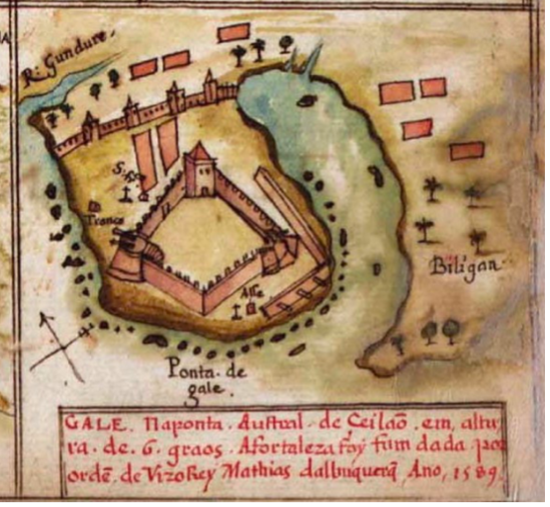

The location of Galle along main sea routes made it a prominent port within Sri Lanka, connecting trade routes between Greece, Arabia, and China and showing records through mapping as early as the 2nd century. The first significant construction by the Portuguese in Galle was of a Franciscan Chapel, in 1543. Fortifications including a wall with three bastions were erected in 1588, facing inland to protect the Portuguese from Sinhalese controlled kingdoms. Assured by their maritime abilities, only earthen and palisade fortifications were erected facing the sea [3].

With growing trade opportunities and the beginnings of concrete colonial establishments, interest from other colonial nations was quickly drawn to the region. The Dutch East India Company arrived in the area in the 1600’s and established control from 1658 to 1796. Overtaking rule of the coastal regions from the Portuguese, the Dutch were likewise unable to overthrow the Kandyan Kingdom, controlled by the Sinhalese in the central highlands of the country. Despite this, the Dutch gradually occupied considerable amounts of territory, including the main points of entry and exit to the land, occupying southern and western Sri Lanka. With the majority of power allotted to the Dutch governor, situated in Colombo, the country was subdivided into provinces and districts, controlled by Dutch officers assisted by loyal Sinhalese and Tamils [4].

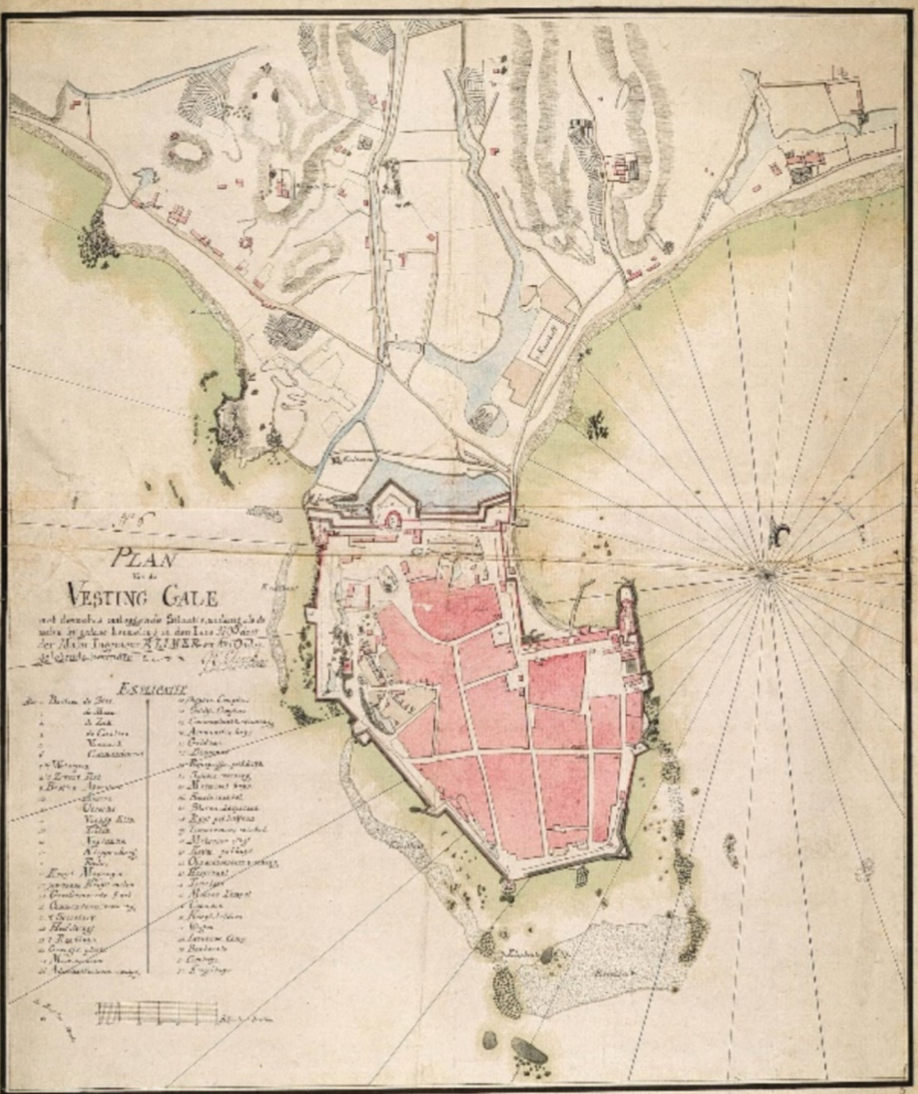

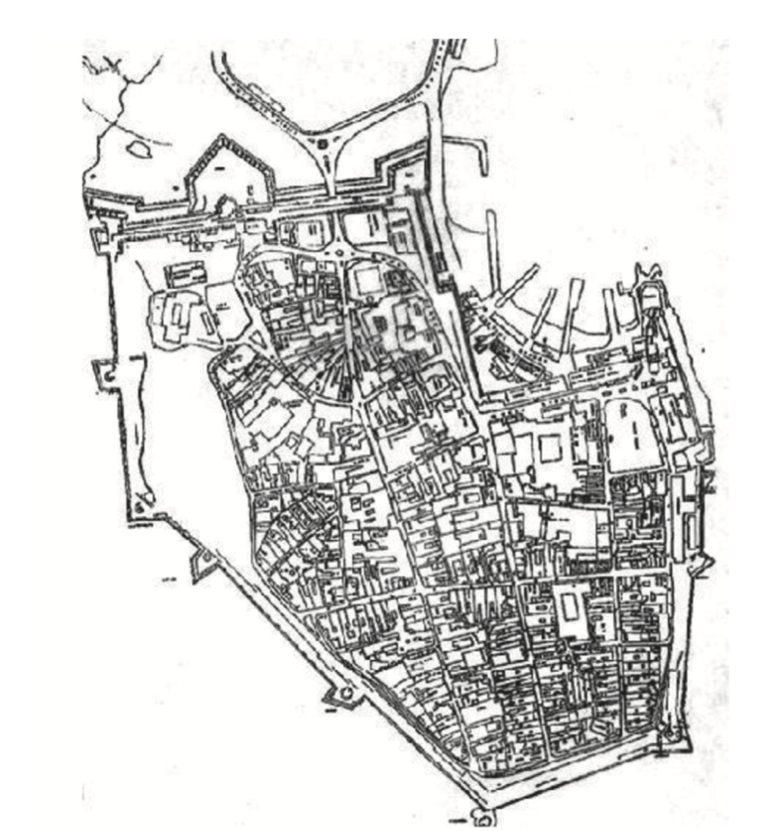

During this gradual occupation of the country, in 1640 a fleet of 12 Dutch ships attacked the Portuguese fort at Galle, gaining control of the port and removing the Portuguese monopoly over important trades in the region. In order to assert and maintain Dutch control over Galle, construction of fortifications began to ward off potential attacks by the English, French, Danish, Spanish, and Portuguese from both landward and seaward directions. Beginning in 1663, ramparts were constructed along the perimeter of the fort. With only two points of entry, the landward gate on the North edge of the fort was constructed with a drawbridge and ditch [5]. Within the ramparts, and defended by 14 bastions, a well-planned town was established.

Including a regular street grid, the town space accommodated residences for 500 families at the time of its full development in the 18th century [6]. Administrative buildings were constructed, including a Commander’s residence, as well as buildings for defense such as a gun house and arsenal. Commercial buildings to support the region’s trade practices, including warehouses and workshops, were woven into the town’s grid [7]. An extensive and ingenuitive sewage system, which operated using seawater at high tide controlled by a pumping station activated by a windmill situated on a bastion, was constructed to serve the town [8].

From its early stages of construction and fortification, Galle fort relied on adaptive practices that drew from the knowledge of both local and colonial occupants in the region to form a successful establishment, illustrating the interaction of European and Asian architecture in the region [9]. With local manpower adapting European models to the cultural, historical, and climactic conditions of Sri Lanka, Galle fort was constructed as a site of adaptation. In the construction of the ramparts, locally sourced coral was used alongside granite. Where aesthetics of the architecture were drawn from European designs, the dimensioning of sites was calibrated to regional metrology. The town grid was populated with wide streets planted with greenery, utilizing local Suriya trees to provide shading [10]. This accumulation of local and colonial influences was reflective of the governing political atmosphere that did and would continue to exist in the region as a mix of European and Asian bodies.

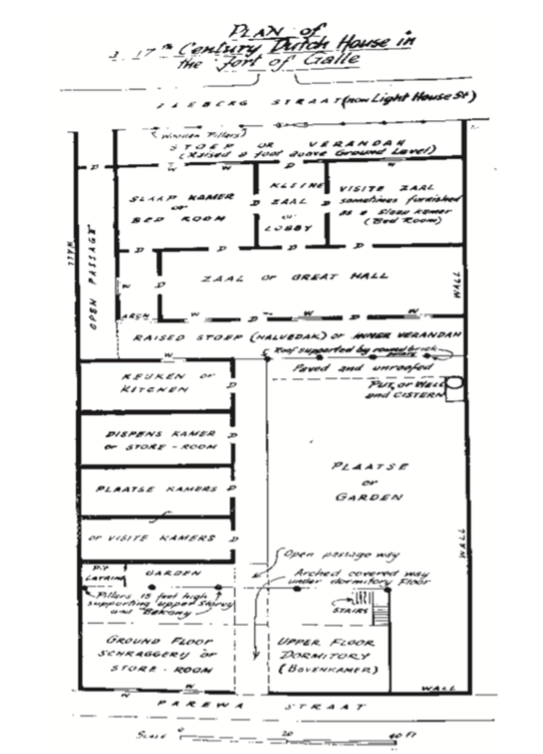

Residential properties within the fort were constructed as townhouses, sharing rows of residences under one joined roof. Each residence was allotted its own garden, with a street front veranda supported by a row of columns. This was an effective adaption of the basic European design, reforming the street fronts as shaded verandas to accommodate the local climate and its high temperatures [11]. The connected verandas would also play a significant role in shaping the community both at the time of its construction, and as the site evolved over time and subsequent occupations, providing a communal space to either physically join or separate community occupants.

In the 400 years since its formal establishment by the Dutch, the architecture of the Galle fort has readily welcomed and adapted to the political and social changes in the region. Under British rule from 1796 to 1900, when the country was referred to as the British Ceylon, the fort took on a new, more formal identity through a number of pointed alterations. These included the introduction of a gate between two existing bastions, a lighthouse, and a tower erected for the jubilee of Queen Victoria [12]. As control of the country was gradually returned to the local Sinhalese and Tamil communities, cumulating in the country’s independence in the mid 1900’s, so too was control of the fort. As local communities inhabited the space, a close-knit community with a strong sense of place and heritage emerged, owing largely to the urban typology of the townhouse verandas and the communal connections they encouraged [13]. Now in modern times, as the fort has been designated a UNESCO world heritage site, attempts to establish a level of stasis and conserve the heritage value of the place have themselves had the consequence of encouraging change by increasing property values and accelerating gentrification of the environment. With local property owners incentivized to rent their street front verandas to commercial businesses, or to perform inauthentic aesthetic renovations to their properties to increase touristic appeal, the site remains in a constant state of rapid change [14].

By gaining an awareness of the constant evolution of the Galle Fort during its existence, perhaps a more authentic conversation can occur in regard to its preservation. Questions remain to be answered on whether attempting to preserve the site in a state of stasis is of authentic value, or whether the site’s history of adaption and evolution is what should be celebrated.

Bibliography

Rajapakse, Amanda. “Exploring the Living Heritage of Galle Fort: Resident’s Views on Heritage Values and Cultural Significance.” Journal of Heritage Management 2, no. 2 (2018): 95-111.

Rajapakse, Amanda. “Transient Heritage Values, Conflicting Aspirations, and Endangered Urban Heritage in the Historic Galle Fort, Sri Lanka.” In The Routledge Handbook on Historic Urban Landscapes in the Asia-Pacific, edited by Kapila D. Silva. 462-472. New York: Routledge, 462-472.

Janakiraman, Aarthi. “The Local Identity Politics of World Heritage: Lessons from Galle Fort in Sri Lanka.” MSc diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019.

Schrikker, Alicia. TANAP Monographs on the History of the Asian-European Interaction. The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2007.

Notes

[1] Amanda Rajapakse and Kapila D. Silva, “Transient Heritage Values, Conflicting Aspirations, and Endangered Urban Heritage in the Historic Galle Fort, Sri Lanka,” in The Routledge Handbook on Historic Urban Landscapes in the Asia-Pacific, ed. Kapila D. Silva (New York: Routledge, 2020) 464.

[2] Alicia Schrikker, TANAP Monographs on the History of the Asian-European Interaction (The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV, 2007), 13-32.

[3] Aarthi Janakiraman, “The Local Identity Politics of World Heritage: Lessons from Galle Fort in Sri Lanka” (MSc diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019), 50.

[4] Aarthi Janakiraman, “The Local Identity Politics of World Heritage: Lessons from Galle Fort in Sri Lanka” (MSc diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019), 51-52.

[5] Aarthi Janakiraman, “The Local Identity Politics of World Heritage: Lessons from Galle Fort in Sri Lanka” (MSc diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019), 51-52.

[6] Aarthi Janakiraman, “The Local Identity Politics of World Heritage: Lessons from Galle Fort in Sri Lanka” (MSc diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019), 49.

[6] Aarthi Janakiraman, “The Local Identity Politics of World Heritage: Lessons from Galle Fort in Sri Lanka” (MSc diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019), 52.

[8] Aarthi Janakiraman, “The Local Identity Politics of World Heritage: Lessons from Galle Fort in Sri Lanka” (MSc diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019), 49.

[9] Amanda Rajapakse and Kapila D. Silva, “Transient Heritage Values, Conflicting Aspirations, and Endangered Urban Heritage in the Historic Galle Fort, Sri Lanka,” in The Routledge Handbook on Historic Urban Landscapes in the Asia-Pacific, ed. Kapila D. Silva (New York: Routledge, 2020) 464.

[10] Aarthi Janakiraman, “The Local Identity Politics of World Heritage: Lessons from Galle Fort in Sri Lanka” (MSc diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019), 49.

[11] Amanda Rajapakse, “Exploring the Living Heritage of Galle Fort: Resident’s Views on Heritage Values and Cultural Significance,” Journal of Heritage Management 2, no.2 (2018): 102-105.

[12] Aarthi Janakiraman, “The Local Identity Politics of World Heritage: Lessons from Galle Fort in Sri Lanka” (MSc diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2019), 49-50.

[13] Amanda Rajapakse, “Exploring the Living Heritage of Galle Fort: Resident’s Views on Heritage Values and Cultural Significance,” Journal of Heritage Management 2, no.2 (2018): 102.

[14] Amanda Rajapakse and Kapila D. Silva, “Transient Heritage Values, Conflicting Aspirations, and Endangered Urban Heritage in the Historic Galle Fort, Sri Lanka,” in The Routledge Handbook on Historic Urban Landscapes in the Asia-Pacific, ed. Kapila D. Silva (New York: Routledge, 2020) 464-466.