Fort York was built in 1793 along the shore of Lake Ontario and exemplifies British military architecture.[1] The strategic location of the fort protected settler colonialism within the nearby Town of York, now known as Toronto. The architecture and history of Fort York reinforced British colonialism and empire in the early 1800s by providing military defence. While the military architecture was meant to be temporary, and became obsolete in the 1840s, the fort then began to passively reinforce colonialism because of historical preservation, beginning in the later 1800s as the urban growth of Toronto surrounded the fort.

A Brief History of Fort York Military Architecture

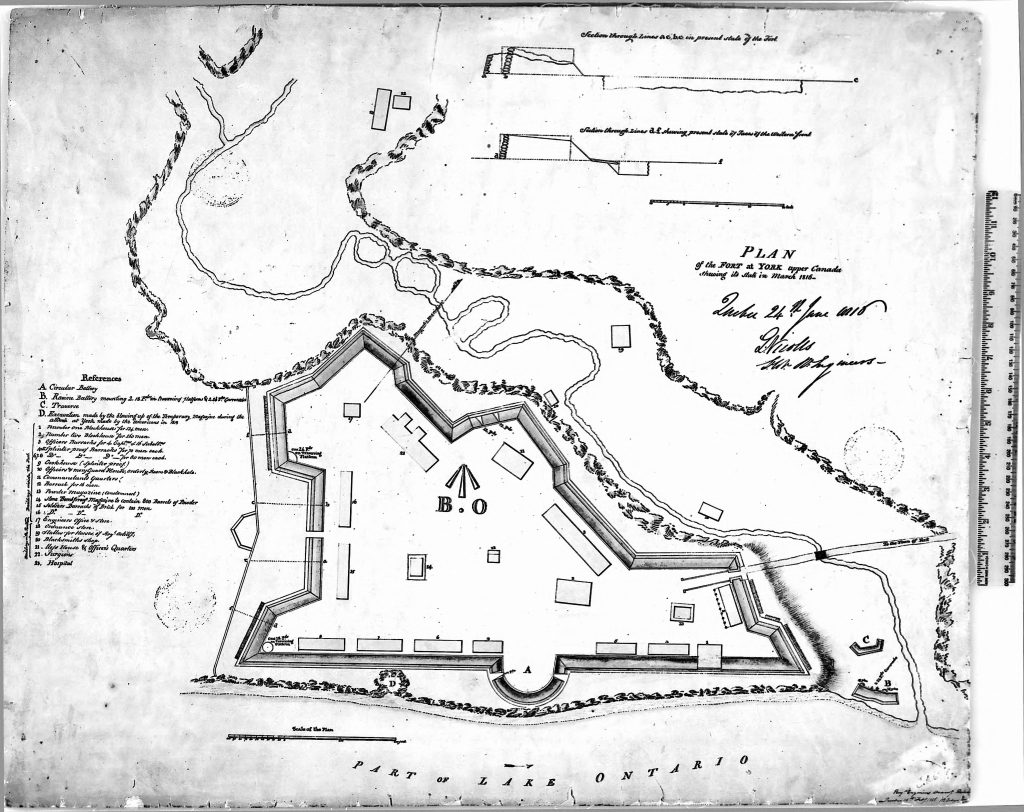

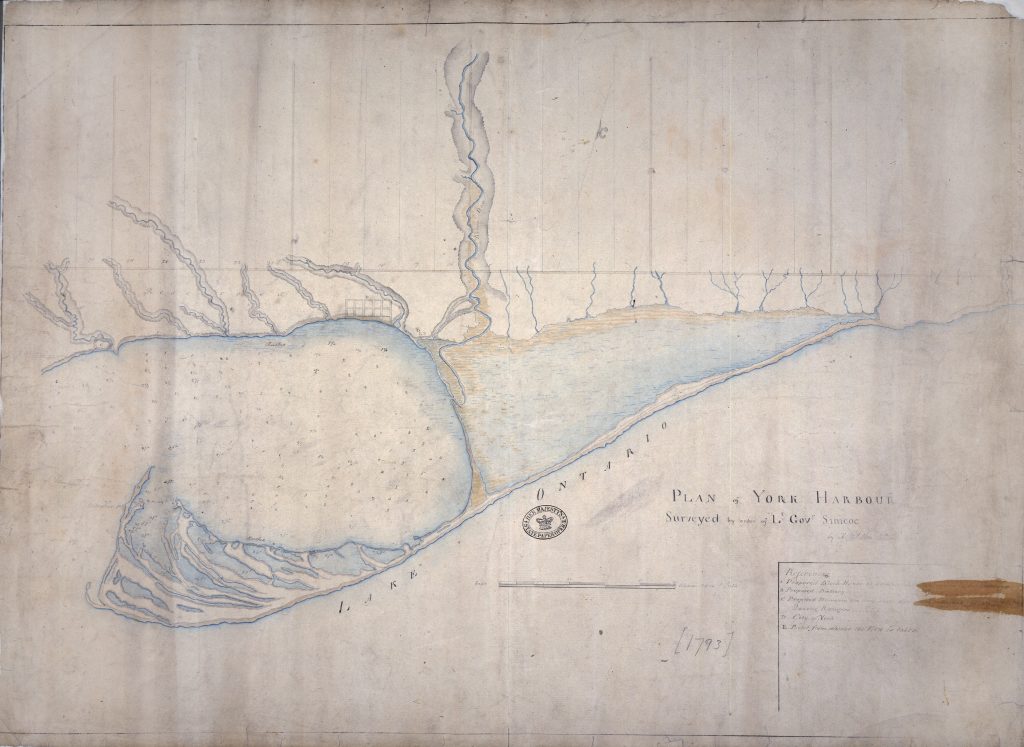

Built in 1793, Fort York is a complex of buildings located along the shore of Lake Ontario.[2] Construction was ordered by Colonel John Graves Simcoe of the British Army.[3] The fort was placed at the opening of York Harbour to act as a base for a naval arsenal to control Lake Ontario. The placement allowed the fort to defend the harbour and the eastern settlement of York, as seen in Figure 1.[4]

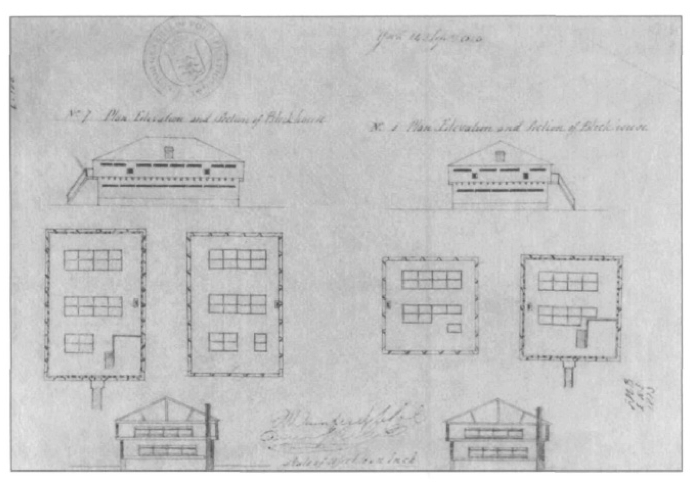

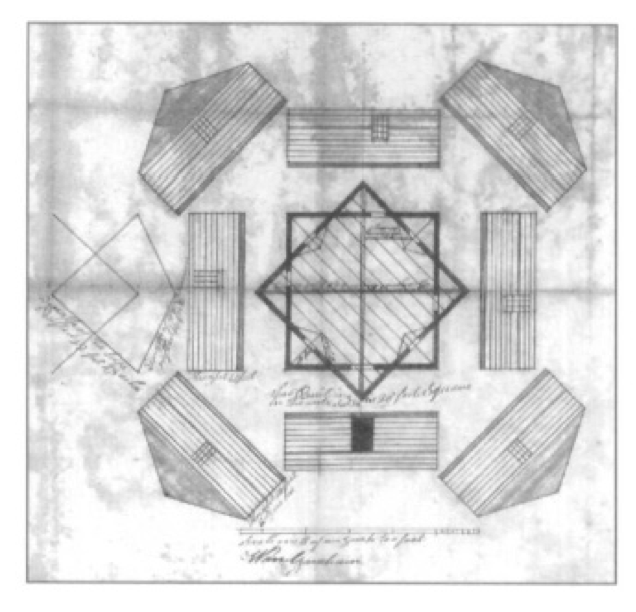

The fort was surrounded by earthworks, a ring of reinforced ground to protect the interior buildings, which can be seen in the plan (fig. 1). Fort York played a significant role in the war of 1812 when British troops retreated, and American forces occupied the fort, later burning down the buildings.[5] The British Army regained possession of the fort in 1813 and began to rebuild their defences.[6] The reconstruction of two blockhouses occurred first, and these military buildings were designed by Royal engineers and constructed quickly in fear of another American attack.[7] The blockhouse was a typology of British military architecture, used for defensive purposes, with a lower level for provisions, storage, barracks, and a second storey acting as a gun platform (see fig. 2 and fig. 3).

Foundations were built out of limestone and shale, with walls made of white pine squared timbers, whitewashed interiors, and a beam joist roof system covered with white pine shakes.[8] Entry doors occur on the second floor, with detachable stairs to improve the defence of the structure from the interior.[9] The buildings were once part of a larger plan and were considered temporary defensive structures, which would be quickly upgraded when sufficient funds became available.[10] Three other blockhouses, roughly seven hundred meters from the fort, were built during this time, and in the 1820s were either deconstructed or fell into disrepair, or a combination of the two. Nevertheless, the Fort York structures continue to prevail, despite their tactical obsolescence in the 1840s. [11]

Urban Growth Reinforcing Colonialism

As the 1800s progressed, the Town of York began to grow. Looking at maps from 1793-1899, one can observe how the civilian settlement expanded, eventually surrounding the Fort York site. In 1793, the Town of York was located on the north-east side of the harbour, and Fort York on the north-west, parallel to the harbour opening, shown in fig. 4; there is a vast distance between the Town and Fort.[12]

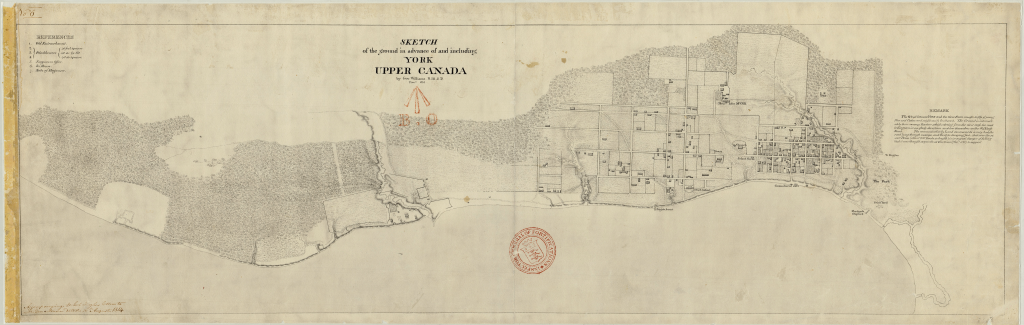

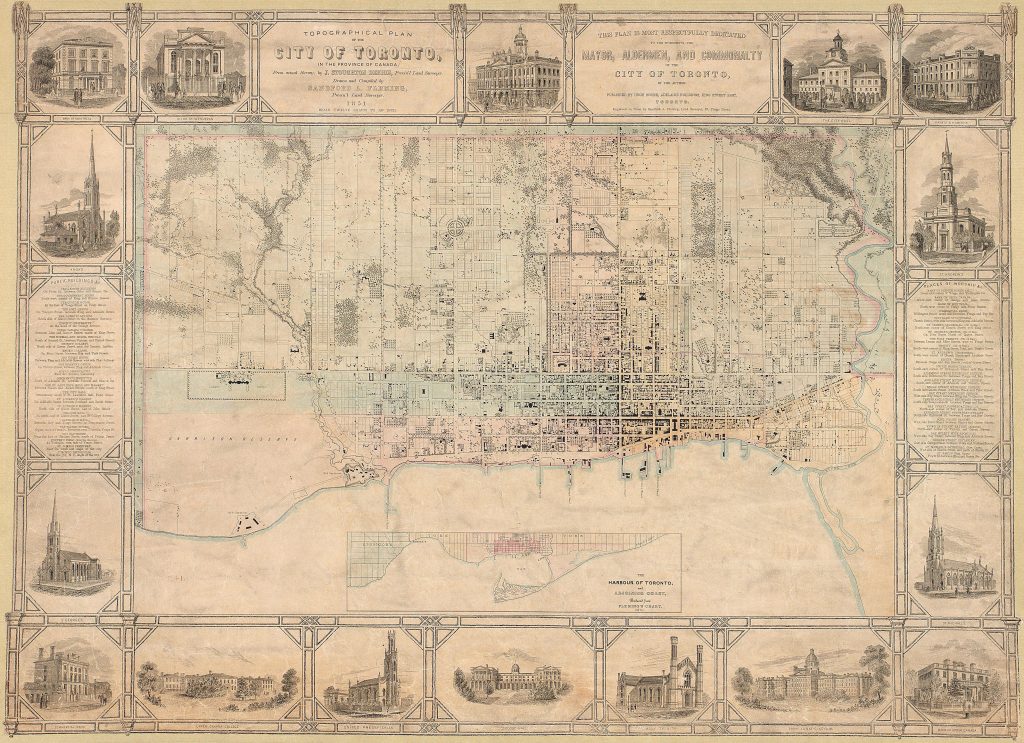

Twenty years later, in 1813, the Town of York has grown, expanding westward (fig. 5).[13] In 1834, the Town of York became Toronto (fig. 6), and the city continued to grow until 1851, when the expansion was directly adjacent to Fort York (fig. 7).[14]

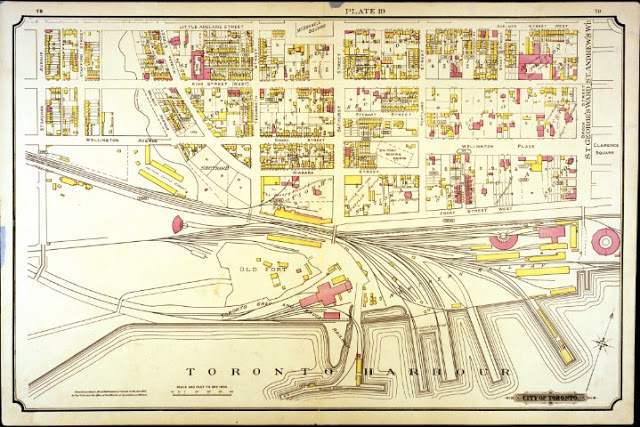

In 1884, the infrastructure of Toronto envelopes Fort York, with train tracks on the northern side, and on the southern side of the Fort was Toronto Harbour along the lake Ontario shoreline.[15] This enveloping of the fort can be seen clearly in the 1899 Toronto Fire Insurance Plan, which labels the CPR freight offices in-between Fort York and the Harbour edge (fig. 8).

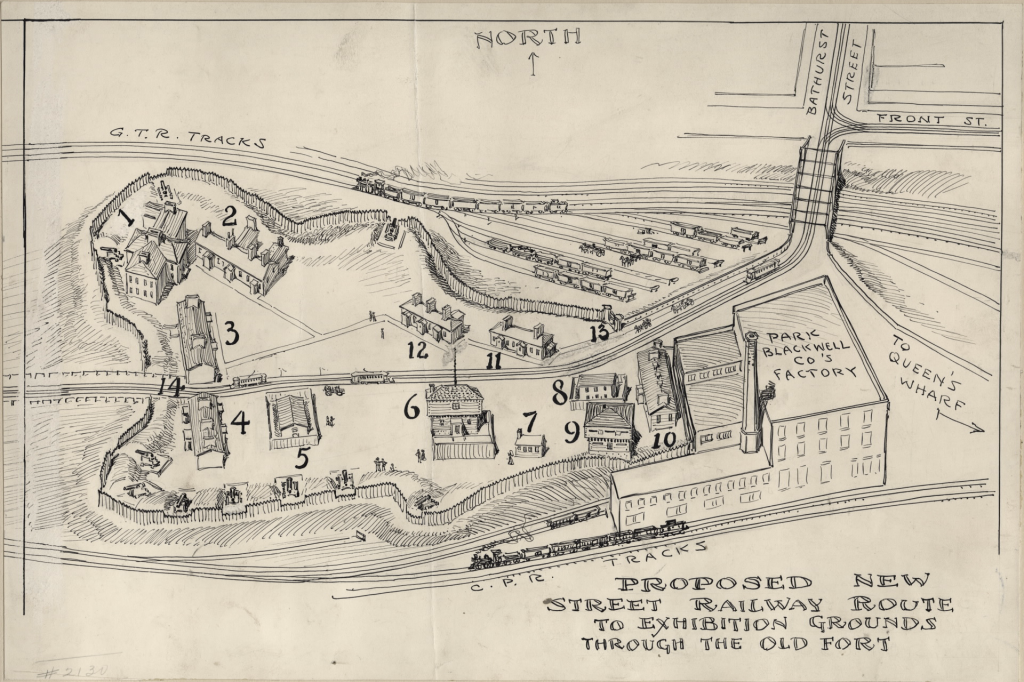

Analyzing the city’s growth is significant because it results from settler colonialism, which was made possible via the military force and the architecture of Fort York, alongside many similar colonial structures across Canada. While mapping and creating land survey documents is inherently a settler colonial process, observing the maps drawn during the respective time periods allows one to see patterns of growth and understand which areas were preserved and what was demolished. Even though Fort York no longer served as an active military site, the buildings are preserved despite the city encroaching around the site. In 1905, a streetcar line was proposed by the city of Toronto to cut through Fort York’s centre (see fig.9).[16] Yet, citizens of Toronto protested the proposal, defending the heritage value of Fort York.[17]

Despite the original intent of Fort York serving as temporary military architecture, preserving these structures places significant value on the history of these buildings, and particularly on settler colonialism of the British empire. Ultimately, preserving these buildings reinforces a settler colonial continuum.

The Continual Reinforcement of Colonialism

Unpacking the centuries of preservation surrounding Fort York indicates the past milieu and how the population of Toronto upheld colonialism. Throughout the 1800s, Fort York was preserved due to vocal public support. While the reasoning for supporting the Fort York preservation is not explicit, one can interpret supporting Fort York as supporting colonialism and the British empire itself. The history of Fort York is similar to the additive history described in Toward Postcolonial Openings: Rereading Sir Banister Fletcher’s “History of Architecture” by Gülsüm Baydar Nalbantoḡlu. In this article, the author critiques Sir Banister Fletcher’s additive framework of updating and distributing historical knowledge. While Fort York is a building, and not an architectural text, similar principles apply. Within Fort York, the buildings have been carefully preserved, renovated, and documented, but the buildings’ use has changed over the years. Nevertheless, the historical framework in which these buildings are viewed has been successively added to, layering colonial history instead of wholly reconsidering and re-contextualizing the history that encapsulates the fort. In contemporary discourse, the historical representation at Fort York has been criticized for upholding colonial power dynamics and selectively omitting and displaying historical information.[18] In the article Colonial Continuum: (De)construction of a ‘Canadian Heritage’ at the Fort York National Historic Site (2020), author Heeho Ryu discusses the erasure of Indigenous communities within contemporary Canadian history and how Fort York “self-perpetuates colonial heteronormativity” which reinforces a settler colonial continuum.[19] Similarly, the article Collaborative Performances of Resistance in Twenty-First Century Toronto: Occupy Toronto and The Encampment (2015) by Andrea Terry describes a two-week participatory exhibition that questioned and challenged the museumified historical framework Fort York is situated within.[20] The collaborative art exhibition was placed in the green space outside of Fort York in 2012, inviting individuals from different backgrounds to reinterpret Canada’s settler colonial history.[21] While The Encampment exhibition thoughtfully reconsidered the historical framework of Canadian settler colonialism, the installation was temporary, and once removed, the historical framework of Fort York remains unchanged. Therefore, the military and colonial framework existing in 1813 are idolized within Fort York, and successive contemporary historical findings are added to the existing history.[22] While it is necessary to maintain historical documentation of past events, stories, and objects, how information is conceptualized and presented can occur in a de-colonized manner, providing a space for reflecting on past events instead of descriptively reliving the history of Fort York.

Beginning in 1793, Fort York provided military defence for the Town of York and the more extensive British colonization of present-day Canada. Until the mid-1800s, the fort was used by the British military to reinforce their settlement. When the fort became militarily obsolete around the 1840s, the fort was preserved. Preservation was an approach that continued into the later half of the 18th century, as the Town of York became Toronto, and the urban fabric grew around the fort. While the fort no longer actively serves to reinforce colonization with military defence, the fort has shifted to passively reinforcing colonialism through functioning as a reminder of military force within the British empire. Through public support via protest, Fort York continues to uphold colonialism through the architecture and historic dialog, a notion that is increasingly critiqued during the 19th-21st century. The contemporary discourse emphasizes problematic Indigenous erasure alongside colonial continuums. When considering the legacy of Fort York, one must consider how the conceptualization and presentation of histories can occur in a decolonized manner, providing a space for understanding and reflecting on past events instead of actively reliving the colonial history.

Footnotes

[1] City of Toronto. “Fort York National Historic Site,” November 23, 2017. https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/museums/fort-york-national-historic-site/.

[2] Carl Benn. “The Blockhouses of Toronto: A Material History Study.” Material Culture Review 42, no. 1 (June 6, 1995). https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/MCR/article/view/17655, 25.

[3] Benn, 25

[4] Benn, 26

[5] Benn, 26-27

[6] Benn, 26

[7] Benn, 25-26

[8] Benn, 31-32

[9] Benn, 31

[10] Benn, 22, 28

[11] Benn, 30

[12] A. Aitken. Plan of York Harbour Surveyed by order of Lt Govr Simcoe. 1793. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3476372

[13] Geo. Williams R.M.S.D. Sketch of the ground in advance of and including York Upper Canada. 1813. http://fortyorkmaps.blogspot.com/2013/02/1813-williams-sketch-of-ground-in.html

[14] J.G. Chewett. City of Toronto and Liberties. 1834. Toronto Public Library. https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-MAPS-R-137&R=DC-MAPS-R-137

Sir Sandford Fleming. Topographical plan of the city of Toronto, in the province of Canada, from actual survey, by J Stoughton Dennis, Provin’l. land surveyor. 1851. https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-MAPS-R-19&R=DC-MAPS-R-19

[15] City of Toronto Fire Insurance Plan. 1899. City of Toronto. https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/accountability-operations-customer-service/access-city-information-or-records/city-of-toronto-archives/whats-online/maps/fire-insurance-plans/fire-insurance-plans-1899/

[16] Owen Staples. Proposed New Street Railway Route to Exhibition Grounds through the Old Fort. Toronto, Ont. 1905. Toronto Public Library. https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-PICTURES-R-2850&R=DC-PICTURES-R-2850

[17] Fort York and Garrison Common Maps. “Fort York and Garrison Common Maps: 1905 Staples: Proposed New Street Railway Route … through the Old Fort.” Accessed February 16, 2021. http://fortyorkmaps.blogspot.com/2013/02/1905-staples-proposed-new-street.html.

[18] Heeho Ryu. “Colonial Continuum: (De)Construction of a ‘Canadian Heritage’ at the Fort York National Historic Site.” Pathways 1, no. 1 (October 2, 2020). https://doi.org/10.29173/pathways10.

[19] Ryu, 8

[20] Andrea Terry. “Collaborative Performances of Resistance in Twenty-First Century Toronto: Occupy Toronto and The Encampment.” Journal of Canadian Studies 49, no. 2 (February 2015): 205–26. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcs.49.2.205, 213-223.

[21] Terry, 215

[22] “Fort York National Historic Site of Canada.” Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=538&i=72485.

Bibliography

Baydar, Gulsum Nalbantoglu. “Toward Postcolonial Openings: Rereading Sir Banister Fletcher’s ‘History of Architecture.’” Assemblage, no. 35 (April 1998): 6. https://doi.org/10.2307/3171235.

Benn, Carl. “The Blockhouses of Toronto: A Material History Study.” Material Culture Review 42, no. 1 (June 6, 1995). https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/MCR/article/view/17655.

Fort York and Garrison Common Maps. “Fort York and Garrison Common Maps: 1905 Staples: Proposed New Street Railway Route … through the Old Fort.” Accessed February 16, 2021. http://fortyorkmaps.blogspot.com/2013/02/1905-staples-proposed-new-street.html.

Fort York and Garrison Common Maps. “Fort York and Garrison Common Maps: Sitemap – Maps of Fort York and Garrison Common.” Accessed February 16, 2021. http://fortyorkmaps.blogspot.com/p/sitemap.html.

City of Toronto. “Fort York National Historic Site,” November 23, 2017. https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/museums/fort-york-national-historic-site/.

“Fort York National Historic Site of Canada.” Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.pc.gc.ca/apps/dfhd/page_nhs_eng.aspx?id=538&i=72485.

Lorinc, John, and Alex Bozikovic. “Preservationist Mounted A Victorious Defence Of Fort York: During His Long, Distinguished Career of Safeguarding Ontario’s Built Heritage, He Took a Special Interest in the Historic Site, Which He Considered the Birthplace of Toronto.” The Globe and Mail. April 28, 2018, sec. Obituaries. https://ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/preservationist-mounted-victorious-defence-fort/docview/2031756615/se-2?accountid=14656.

Ryu, Heeho. “Colonial Continuum: (De)Construction of a ‘Canadian Heritage’ at the Fort York National Historic Site.” Pathways 1, no. 1 (October 2, 2020). https://doi.org/10.29173/pathways10.

Stewart, Andrew M. “New Stories from Toronto’s Old Fort York: Assets in Place.” Arch Notes (Newsletter of the Ontario Archaeological Society), 2008. https://www.academia.edu/4309377/New_Stories_from_Torontos_Old_Fort_York_Assets_in_Place

Terry, Andrea. “Collaborative Performances of Resistance in Twenty-First Century Toronto: Occupy Toronto and The Encampment.” Journal of Canadian Studies 49, no. 2 (February 2015): 205–26. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcs.49.2.205.

Figures

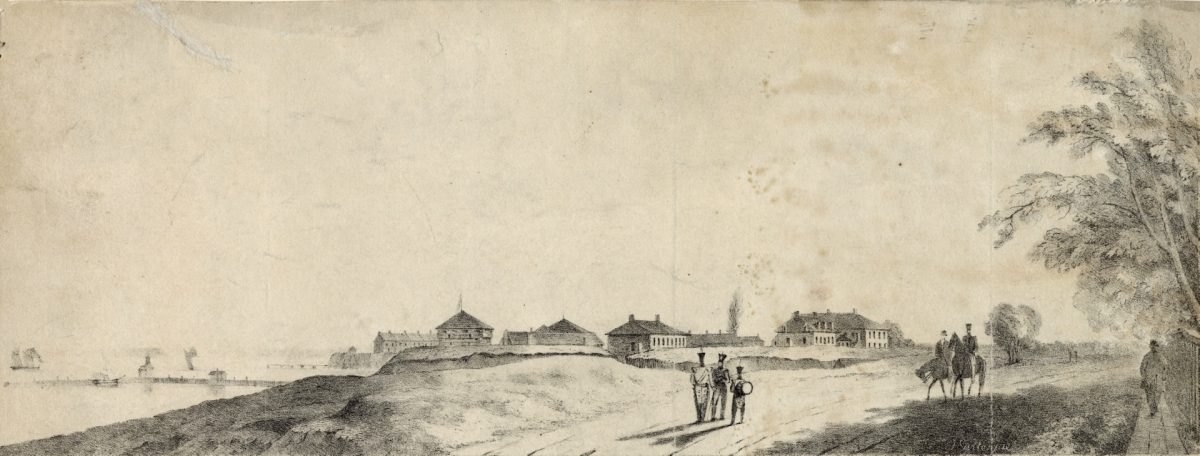

Cover Image. John Gillespie. Fort York. 1845. Toronto Reference Library. https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-PICTURES-R-2910&R=DC-PICTURES-R-2910

Figure 1. ROYAL ENGINEERS Nicolls, G. Duberger, J.B. Plan of Fort at York, Upper Canada, showing its state in March 1816. 1816. University of Toronto Map and Data Library. https://mdl.library.utoronto.ca/collections/scanned-maps/plan-fort-york-upper-canada-showing-its-state-march-1816

Figure 3. Block Houses No. 1 (left) and No. 2 (right) from an 1823 sketch. National Archives of Canada, NMC-5432.

Figure 4. Town of York Blockhouse Schematic Illustration. 1799. National Archives of Canada, NMC-5427.

Figure 5. A. Aitken. Plan of York Harbour Surveyed by order of Lt Govr Simcoe. 1793. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3476372

Figure 6. Geo. Williams R.M.S.D. Sketch of the ground in advance of and including York Upper Canada. 1813. http://fortyorkmaps.blogspot.com/2013/02/1813-williams-sketch-of-ground-in.html

Figure 7. J.G. Chewett. City of Toronto and Liberties. 1834. Toronto Public Library. https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-MAPS-R-137&R=DC-MAPS-R-137

Figure 8. Sir Sandford Fleming. Topographical plan of the city of Toronto, in the province of Canada, from actual survey, by J Stoughton Dennis, Provin’l. land surveyor. 1851. https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-MAPS-R-19&R=DC-MAPS-R-19

Figure 9. Fire Insurance Plan. 1899. City of Toronto. https://www.toronto.ca/city-government/accountability-operations-customer-service/access-city-information-or-records/city-of-toronto-archives/whats-online/maps/fire-insurance-plans/fire-insurance-plans-1899/

Figure 10. Owen Staples. Proposed New Street Railway Route to Exhibition Grounds through the Old Fort. Toronto, Ont. 1905. Toronto Public Library. https://www.torontopubliclibrary.ca/detail.jsp?Entt=RDMDC-PICTURES-R-2850&R=DC-PICTURES-R-2850