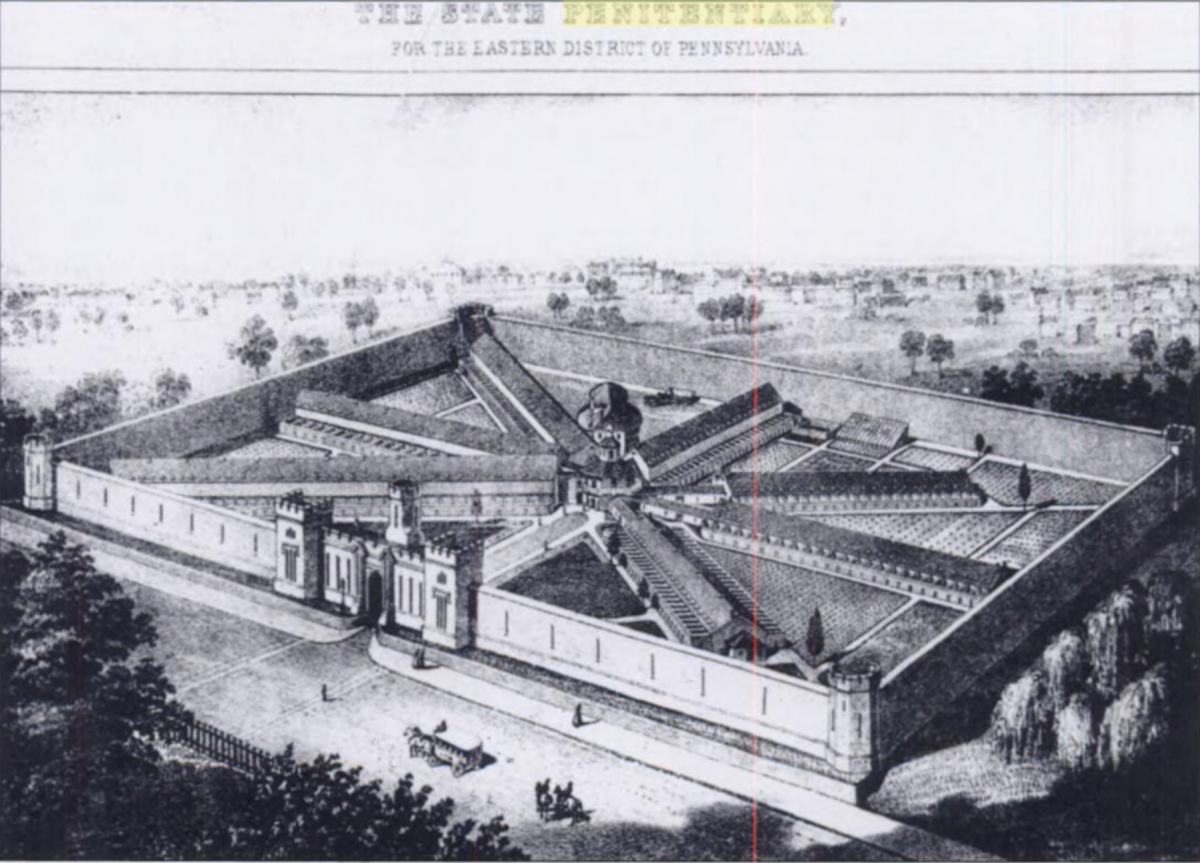

The Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP) was built between 1821-9 and designed by Architect John Haviland in the outskirts of Philadelphia. Noticeably atop of a hill, the prison’s feudal-styled walls enclose the 12-acre site and present an ominous symbol to discourage illegal behaviour in the city. The ESP was initiated by the Philadelphia Society for the Alleviation of Miseries on Public Prisons as a campaign to replace their degrading prisons of the 18th century. This state-of-the-art penitentiary operated for 142 years influencing hundreds of penitentiaries around the world and eventually closing in 1971.[1] It is now a National History Landmark and operates as a museum. Its history can be understood as a testing ground for colonial reform through systems of architecture, punishment, and religion. More specifically, an institution in which total control could be exerted to form the desired character of its inmates, eventually releasing them as mentally cured citizens ‘ready’ for society. It could be summarized as an architecture of character building. The institutional architecture of such drew direct roots to European prisons, asylums, schools, and factories notably in Britain, Scotland, and Rome. These institutions were formed with the belief that a person could be transformed by a rigid system of control using discipline, sanitation, silence, work, and religion to rinse away the ‘diseased’ minds or shape the minds of innocent children.[2] A system by which architecture played a crucial role to create a machine-like environment that produced men and women sculpted for the society conceived by the ruling party. This pattern is evident throughout the colonial Americas and can be found in boarding schools, residential schools, labour factories, religious practices, and even seen in many radial or grid city plans today. The ruling party imposed their belief system on others, with genuine certainty that it was in the best interests of greater humanity. This hegemonic controlled system was made possible in these institutions by their ability to maintain total control without any outside distraction or resistance. As a result, it could be argued that this was prime testing grounds for colonialization and could be worthy of research by historians and current social activists working towards colonial reconciliation in the colonies. The history of institutional control in Europe can be seen as the precursor to colonialism as they used these same tools to shape the New World. Exposing this history can spark dialogue and initiate healing towards the oppressed and even identify other invisible examples of colonialism that pervade our culture and built environment today.

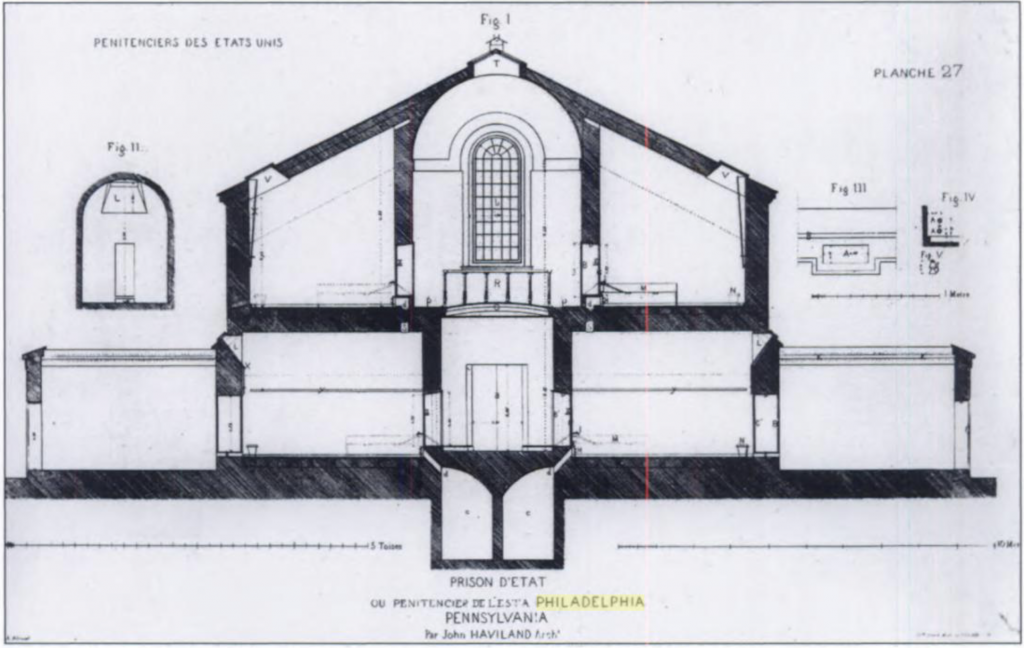

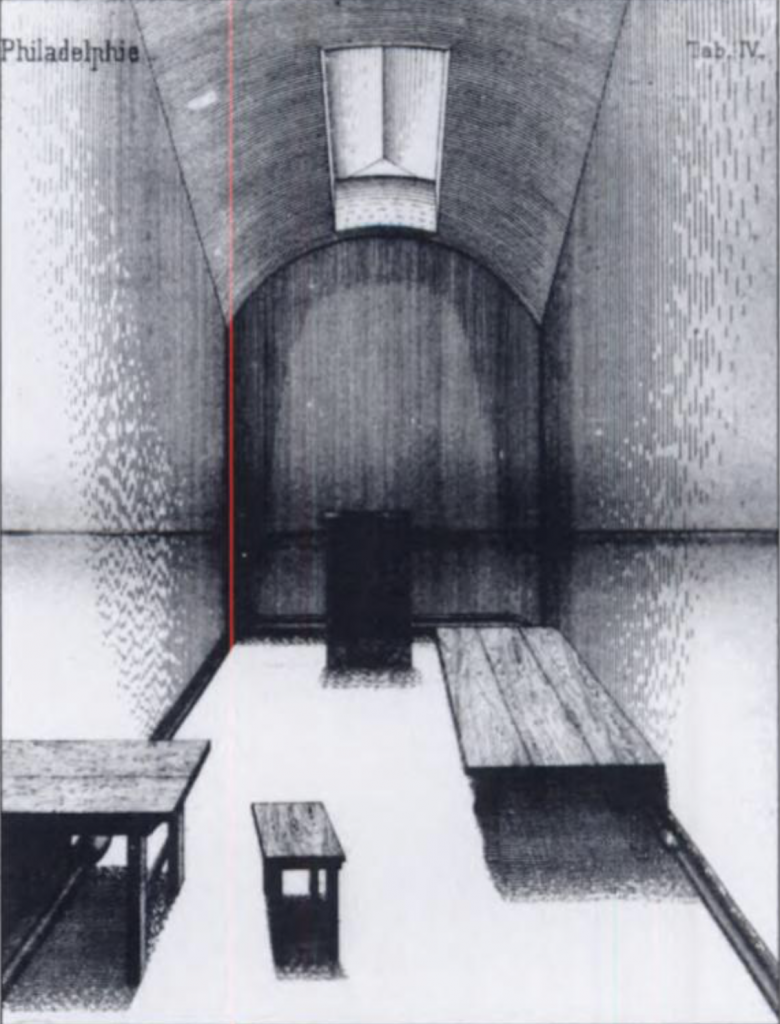

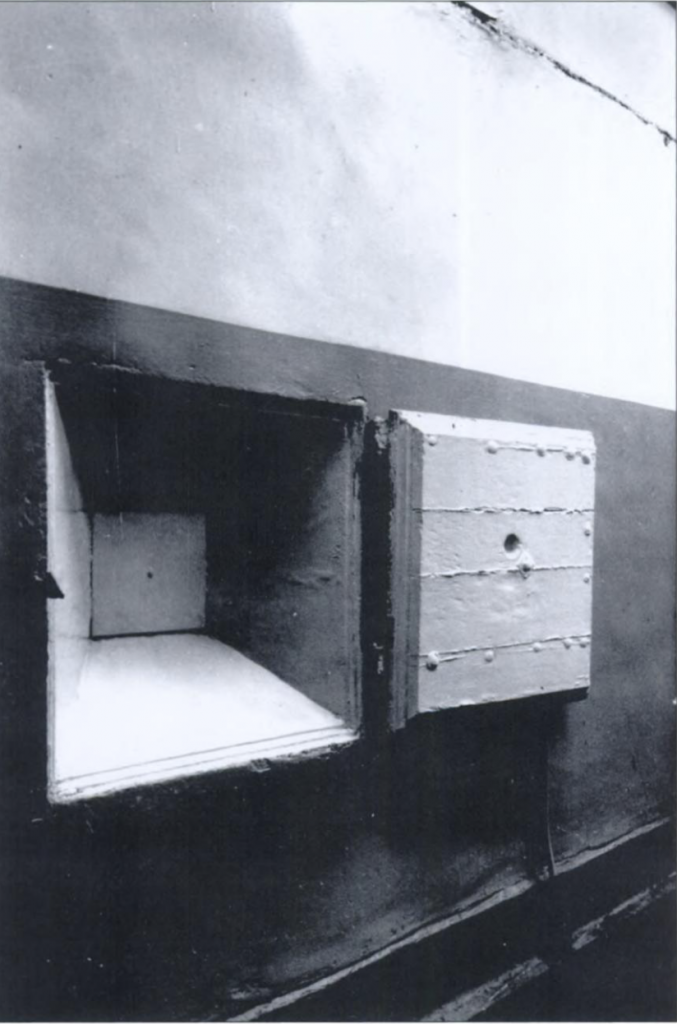

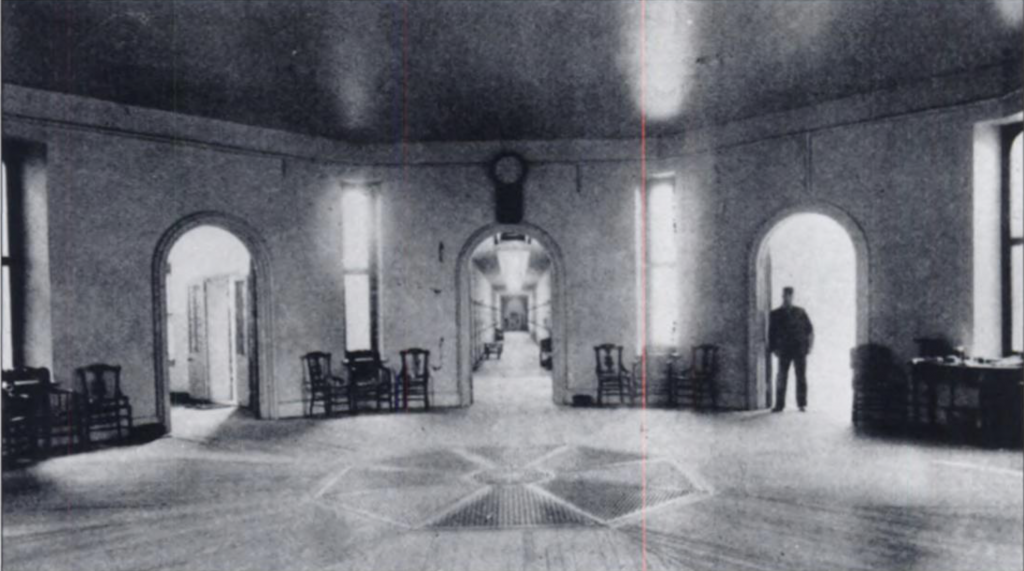

Initially designed to reform inmates with religion, job training, and solitary confinement, the prison was organized in a ‘spoke and wheel’ plan, conceived of 7 cell blocks arrayed around a central control tower and positioned within the perimeter stone wall. Although not considered a panopticon structure, the radial plan originated from Jeremy Bentham’s prison model of which a single guard could monitor the entire prison from a central control point[3]. The mass and materiality of the surrounding wall and the metal gates presented a permanence and indestructibility that resembled those in power. Within the prison was a sophisticated hospital, kitchen, and laundry room. The 450 prisoners were confined to their cells 24-hours a day without visitors or ever seeing other inmates or guards. Individual barrel-vaulted and sky-lit cells lined the perimeter of each corridor cell block. The skylights and cathedral-like ceilings promoted penitence through god and echoes of clanging metal gates and voices could be faintly heard. On the lower levels, outdoor exercise spaces were attached to the cells for inmates to use 1-hour a day to receive fresh air and sunlight. The upper-level inmates in the larger cell blocks were hooded and brought to designated outdoor spaces, concealing their identity entirely. Inmates were given tools and food through a small window of the sealed sliding door. They were allowed to learn trades in their cells and were provided with appropriate machines and work benches. Individual latrines and water faucets were attached to each cell, which at the time was a state-of-the-art plumbing system encouraging hygiene (morale purity) to the lower class, which was difficult to control outside of the prison[4]. By the 20th century, solitary reform was rightfully deemed inhumane, and the prison pivoted its reform system. The ESP converted exercise yards to recreation fields, group workshops, school spaces, a mill, bakery and a synagogue. The prison also added 8 new wings, some of which were built by the prisoners. In this period, it was described as a city within a city, with thriving sports leagues, efficient industry work and growing support for education. The cells were no longer assigned to individual inmates, partially in response to overcrowding and high maintenance costs, yet more importantly to end the painful torture of absolute solitude[5]. English writer and social critic, Charles Dickens, visited ESP in 1842. He met with prisoners and toured the prison in shock and sadness of this punitive system. In American Notes, he writes “my firm conviction is that independent of the mental anguish it occasions—an anguish so acute and so tremendous, that all imagination of it must fall far short of the reality—it wears the mind into a morbid state, which renders it unfit for the rough contact and busy action of the world. It is my fixed opinion that those who have undergone this punishment, must pass into society again morally unhealthy and diseased.”[6] Here, he described a failing system that opposes the initial goal of producing people clean of the mind and critiques its founders for being unable to place themselves in the prisoner’s shoes. The system of solitary confinement eventually buckled under the pressure of cost, space and human nature.[7] Yet, the concept of penitentiary as a tool to control the malleability of the mind continued and parallels can be observed in systems of colonialization throughout the Americas.

The ESP was a small city hidden from the outside world and could operate independently, testing systems of control and reform. Yet, because of its small scale in comparison to the greater city of Philadelphia, it could be critiqued in greater detail, even ridiculed and deemed inhumane. Colonialism was a system at the time, much too large to expose, a system that shaped the character of the people in the interest of the ruling class. The same European systems of education, labour, infrastructure and religion held a firm grasp over the lower class, slaves and indigenous populations, and was used around the colonies as a tool to colonize and assimilate people. Even today, colonialism continues, yet remains invisible to so many. The ruling class, color and sex control a system not so dissimilar to the East State Penitentiary. We may not have the physical walls of a prison, however, forms of colonial agency are embedded throughout our society. Our institutional buildings, city planning, hospitals and ideals are rooted in colonialism. From a young age, we are placed in an institutional setting called ‘school’ and are taught a standardized education. Standardized tests, especially in the US and grade averages decide our children’s future. We then graduate to the workforce and are integrated into an efficient machine of labour and capitalism. If you stray too far away from this projection, you often suffer in poverty or are on the fringes of society. In a worst-case scenario, one may fail in this structured society and be placed in a penitentiary or asylum that will attempt to mold you back into a law-abiding citizen or rather keep you away from society indefinitely. How different is the city (colonialism) from the city within the city (ESP)?! Conclusions can be drawn that they share many of the same systems of control. Studying the history of architecture and sociological methods of control in penitentiaries such as ESP can uproot the same systems at play in the so-called ‘free’ society beyond the walls of a prison. This could foster conversation, critical thought and reconciliation towards marginalized groups throughout the past and present forms of colonialization.

Bibliography

Cassidy, Michael John. On Prisons and Convicts: Remarks from Observation and Experience Gained during Thirty Years of Continuous Service in the Administration of the Eastern State Penitentiary, Pennsylvania: Addressed to Members of Societies Interested in Prison Management. Philadelphia: Patterson & White, 1894.

Dickens, Charles. “Philadelphia, and Its Solitary Prison.” In American Notes, 81–91. Avon, CT: Cardavon Press, 1975.

Dolan, Francis X. “A City Within A City.” Essay. In Eastern State Penitentiary, 7–31. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2007.

Markus, Thomas A. Buildings & Power, 39-146. London and New York: Routledge, 1993.

[1] Dolan, Francis X. “A City Within A City.” Essay. In Eastern State Penitentiary, 7–31. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2007.

[2] Markus, Thomas A. Buildings & Power, 42. London and New York: Routledge, 1993.

[3] Markus, Thomas A. Buildings & Power, 127. London and New York: Routledge, 1993.

[4] Dolan, Francis X. “A City Within A City.” Essay. In Eastern State Penitentiary, 16-18. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2007.

[5] Dolan, Francis X. “A City Within A City.” Essay. In Eastern State Penitentiary, 8. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2007.

[6] Dickens, Charles. “Philadelphia, and Its Solitary Prison.” In American Notes, 81–91. Avon, CT: Cardavon Press, 1975.

[7] Dolan, Francis X. “A City Within A City.” Essay. In Eastern State Penitentiary, 8. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2007.