Question 2: “Coyote Pedagogy is a term sometimes used to describe King’s writing strategies (Margery Fee and Jane Flick). Discuss your understanding of the role of Coyote in the novel.”

The term “Coyote Pedagogy” offers great insight into the figure of Coyote in Green Grass Running Water, as a teacher.

What struck me the most when I did some research into the Coyote figure in First Nation’s mythology was the diversity in which s/he can be portrayed. Coyote is hard to pin down or define because s/he can be/is so many different things, depending on the story.

The Coyote mythlore is one of the most popular among the Native Americans. Coyote is a ubiquitous being and can be categorized in many types. In creation myths, Coyote appears as the Creator himself; but he may at the same time be the messenger, the culture hero, the trickster, the fool. He has also the ability of the transformer: in some stories he is a handsome young man; in others he is an animal; yet others present him as just a power, a sacred one (Kazakova 1997).

In this novel, Coyote can be seen to act as all of the aforementioned “types” in some way or another. Blanca Chester describes how, “Coyote’s essential nature, it could be said, is a storied one that contains multiple realities” (56). This understanding of Coyote as multifaceted really guided my reading of him/her in the novel and I think exists at the core of King’s narrative. All things/beings contain multiple realities.

My very first impression of Coyote’s function in the novel is that s/he seems to be able to move through time, bridging the gap between the past and the present. This, in conjunction with the structure of the novel (which does not follow a classic linear structure), demonstrates a way of knowing time that is cyclical in nature (as demonstrated by the Medicine Wheel). The ending is the beginning, the past and the present collide and myth and reality cannot be teased apart easily.

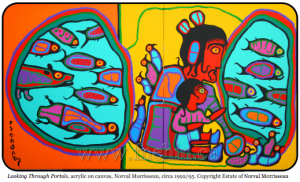

Looking Through Portals, acrylic on canvas, Norval Morrisseau, circa 1992/95. Copyright Estate of Norval Morrisseau

Here is a wonderful quote from Chester that really helps to understand the importance of blending and bridging gaps in King’s novel:

The inclusion of newer, European elements into fresh versions of traditional stories ensures their vitality. When King uses traditional stories in the context of the novel form, the stories themselves are re-created and they simultaneously re-create the world—again and again. The stories continue to theorize, and thus to create, Native reality. Not to blend the new into the old would suggest stasis, the stories frozen through a (printed) moment in time. It would suggest stories as word museums rather than as vital and living, like language and culture themselves (59).

This useful passage really highlights King’s advocacy for the fluid nature of stories and I believe, of the people telling those stories.

Coyote crosses boundaries in other ways as well. For example, he transgresses the bridge between Indian and Western culture, between animal and human and between the reader and the novel. This idea of Coyote being able to cross borders is discussed in Margery Fee and Jane Flick’s article, “Coyote Pedagogy: Knowing Where the Borders Are in Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” They explain that, “Coyote pedagogy requires training in illegal border-crossing,” highlighting the fact that Coyote is not only a teacher, but also a trickster (131). Indeed, I believe it is because Coyote crosses these so called “illegal borders” and is constantly in opposition to figures of authority, that we are able to learn from him. Through Coyote, King may be teaching us to question our preconceived ideas and stories about the world and the authority from which they stem.

In some ways, Coyote can also be seen as an everyman figure. S/he connects the audience to the novel, acting as a sort of guide between the different settings and worlds. Furthermore, the lessons s/he learns, we learn right along with him/her. When s/he is told to “pay attention,” we are simultaneouslybeing told to pay attention (King 38,100, 104 etc.). Coyote, like the reader, makes mistakes and misinterprets things often. For example, when he thinks there can only be one Coyote:

“And there is only one Coyote,” says Coyote.

“No,” I says. “This world is full of Coyotes.”

“Well,” says Coyote, “that’s frightening.”

“Yes it is,” I says. “Yes it is.” (King 272)

In this novel we (and Coyote) have already met old Coyote, so we know that Coyote is wrong in assuming there is only one Coyote. And if the reader knows anything about this figure in First Nation’s mythology, they will know that there are many, many versions. Therefore, perhaps King is using this as an exemplifier to show our tendency to reduce ideas, peoples or cultures, when really it is impossible to do so.

Through his portrayal of Coyote, Kings helps us understand the complexity of every story and the importance of truly listening, rather than attempting to understand. The chaotic form of the text is puzzling to the reader and King knows this. With the help of Coyote he is encouraging the reader to look deeper, to listen louder and to challenge our own assumptions about the nature of the world. By engaging in these behaviours, we become one step closer—not necessarily to understanding the other—but to finding common ground.

* * *

bisbeejim. “The Medicine Wheel – 1 of 3.” Online video clip. Youtube, Sep. 18 2007. Web. 10 Jul. 2014.

Chester, Blanca. “Green Grass, Running Water: Theorizing the World of the Novel”. Canlit.ca: Canadian Literature, 9 Aug. 2012. Web. 10 Jul. 2014.

“Cyclical Worldview: Understanding Environmental Health from a First Nations Perspective.” First Nations Environmental Health Innovation Network, n.d. Web. 10 Jul. 2014.

Fee, Margery and Flick, Jane. “Coyote Pedagogy: Knowing Where the Borders Are in Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canlit.ca: Canadian Literature, 2012. Web. 10 Jul. 2014.

Kazakova, Tamara. “Coyote.” MMIX Encyclopedia Mythica™, 6 Jul. 1997. Web. 10 Jul. 2014.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

I really enjoyed your insight into Coyote’s purpose in GGRW. I agree with your comment “with the help of Coyote he is encouraging the reader to look deeper, to listen louder and to challenge our own assumptions about the nature of the world.” If you’ll allow me to, I’d like to expand on your comment “by engaging in these behaviours, we become one step closer—not necessarily to understanding the other—but to finding common ground.”

My perception of Thomas King’s intent is that he uses the figure of Coyote not only to virtually bridge the two realities of realistic and mythological worlds but to plant the idea that Coyote’s mishaps represent a big part of his life, which does not shadow the fact that the First Nation trickster is a positive hero. I feel (don’t know for sure!!!) that King uses Coyote and Coyote’s contemporary heroes’ duality (probably not the right word) so we can understand better the trickster’s actions and their consequences

for the other heroes.

I felt the end message is that Thomas King initiates thought towards the readers of his novel in that as long as human beings prefer to separate themselves in ethnic and other different kind of groups, there are going to be misunderstandings and people, or spiritual images, who will try to fix them up, just like Coyote tries to do.

My question to you is, of course, do you agree? But also, from a First Nation perspective, why is idea incredibly important in how we live in society today?

Hi Kristin, thanks for the comment!

Yes, I definitely think that part of the reason King uses Coyote’s “multiplicity” as a character to help us better understand the trickster’s actions/their consequences on the other heroes of the novel. That’s what I love about Coyote– he is so versatile! I think I may need you to clarify your second question for me… sorry! I also have a question for you: what do you think King is trying to say about human beings preferring to separate into group… does he think it is good, bad, unavoidable? Does he offer a solution?