Or in this case, every woman.

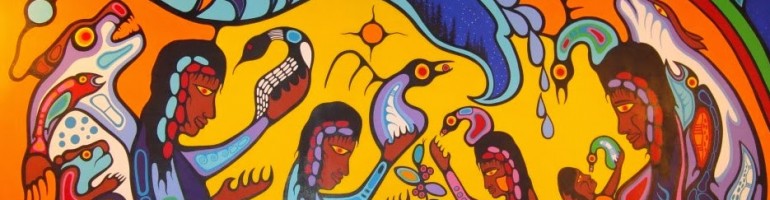

Water flows between the different sections, setting and characters of the text. King uses the story of the flood to weave together a narrative that subverts classic Western traditions and decolonizes them. Here is a closer look at some of the allusions he uses to do this:

Changing Woman

Changing Woman makes her appearance on page 104 and she happens to be a figure from Navajo mythology. The Navajo are the largest federally recognized tribe of the United States. This autonomy is replicated in the character of Changing Woman in King’s novel.

Witherspoon describes how the Navajo way of knowing is gendered, with male energy distinguished by a “static reality,” and female energy by an “active reality” (141).

According to Myth Encyclopedia, a crucial element of Changing Woman’s character is that she is constantly changing, but she never dies. In fact, the cyclical nature of her existence mimics the circle of life and the structure of King’s novel. In the winter she ages and in the spring she is renewed once more into a young woman. “In this way, she represents the power of life, fertility, and changing seasons.”

It is easy to see that Changing Woman fits into this “active reality,” with even her name being directly opposed to stasis. Witherspoon describes how, “The earth and its life-giving, life sustaining, and life-producing qualities are associated with and derived from Changing Woman. It is not surprising, therefore, that women tend to dominate in social and economic affairs… [and] the clans are matrilineal” (141).

Though historically Changing Woman represents fertility, there are elements of the homoerotic in King’s novel (moreso a little later than my pages, but I will draw on it here). King highlights the feminine power that Changing Woman holds, completely independent from men, or classic reproduction. He also places her as the hero of Western myths and stories. On page 105, I was stricken by the resemblance of her actions to those of Narcissus from mythology.

Narcissus, enraptured by his own reflection.

She could see herself reflected in that beautiful Water World.

Hmmmm, she says, not bad.

Everyday, Changing Woman goes to the edge of the world and looks down at the water and when she does this, she sees herself. Hello, she says.

And each day, Changing Woman leans a little farther to get a better look at herself.

I love this passage. I love that she is not punished like Narcissus is. She looks into the water and she sees herself and she likes what she sees. A very empowering image, perhaps highlighting sexual awakening or simply, awakening. Yes she falls in, but that is her nature: change. Narcissus is cursed to stare at himself for eternity or in some version he falls into the water and dies, both are are states of stasis. This passage also reminds me of the title quote of this blog from Moby Dick: “The sea, where each man as in a mirror finds himself.” Such a gendered statement, but here King inverts it, Changing Woman finds herself in that same mirror that in the Western world is/was reserved only for men. These are simply a couple of examples of how King subverts Western hierarchies. Here Native femininity is powerful beyond and separate from white masculinity.

Ishmael

Ishmael is the name that Changing Woman chooses to take later in the novel (despite being told she shouldn’t). The name is both a biblical reference and an allusion to the narrator of the classic American novel Moby Dick.

Both men are wanderers and “outcasts in a barren landscape” (Schmoop). Ishmael from Genesis, is banished by his father and wanders the desert, Ishmael from Moby Dick wanders the vast ocean. Both are rescued. King’s Ishmael, besides being a woman, is different because, though she is a wanderer and she does get in some trouble (prison), she is not rescued. She rescues herself. Also she does not need rescuing from wandering, she wants to escape from captivity so that she can wander.

Eli Stands Alone

Eli is tied to Ishmael and Changing Woman. (Both Ishmael and Eli, which are biblical names have the word “el” in their names, which mean God.)

Eli can be interpreted as King’s version of Noah. While the Christian Noah is a disgusting character in this novel, Eli embodies the hero that the Christian Noah is supposed to be. He is on a mission to save his people from a terrifying flood.

Why “Stands Alone”? One reason is that Eli’s character refers to the First Nation’s Manitoba MLA Elijah Harper. Harper rose to fame after being a crucial player in the rejection of the Meech Lake Accord, an attempt at Canadian constitutional reform (specially designed to get Quebec to accept the Constitution Act) and that had been negotiated in 1987 without the input of Canada’s First Nations. By opposing this Accord, Harper drew attention to the government’s failure to give adequate attention to negotiating issues of self-governance (Flick 150).

Another reason he may be called “Stands Alone,” is that Eli was isolated from his First Nation’s heritage for much of his life, living instead as a university professor of literature. In this way, he stands alone or apart from the rest of his people. I found it interesting that Eli is referred to as having “wanted to be a white man,” simply because he decided to be university professor (King 80). To me this illustrates the idea discussed in this class, of Westerners having ownership over literature. It is interesting that it is the First Nations people in this book that embrace this attitude, which may illustrate the effect years of repression can have on a culture, but also demonstrates the catch twenty-two that modern-day First Nation’s people may have; having to decide between Western culture and Aboriginal culture. I would argue that King fights against this attitude (held by both parties) and is trying to illustrate the complexity of “the Indian” and really of all people. In this section Eli subconsciously makes the decision to stay and embrace his First Nation’s identity, thus leaving behind his “white man” life.

The Dam

The dam is obviously tied to Eli.

The dam represents Westerners imposing on First Nation’s culture and land and emphasizes that this is still an issue in modern times. This mimics how Noah later imposes on Changing Woman and I believe ties Eli to the feminine.

I also read the dam as being an allusion to Adam (and Ahdamn). The phrase “Ah damn” is something someone would say when they realize they’ve made a mistake. In the Garden of Eden in Genesis, everyone is obsessing over original sin, as if this is the ultimate mistake. This may be far fetched, but perhaps King is drawing our attention to the irony that we still obsess over a mistake made in a story, when we continue to commit horrible injustices on our fellow human beings. The real mistake then, could be seen as white repression and intrusion on First Nation’s cultures and land, signified in King’s story by on huge mistake, a dam. We have mistaken what sin really is.

…and it is a mistake, that the Western world is constantly justifying:

[Eli] “So how come so many of them are built on Indian land?”

[Sifton] “Only so many places you can build a dam.”

[Eli] “Provincial report recommended three possible sites.”

[Sifton] “Geography. That’s what decides where dams get built.”

[Eli] “This site wasn’t one of them… None of the recommended sites was on Indian land.”

[Sifton] “I just build them, Eli. I just build them.” (King 111)

In this passage King shows us that the choice to build the dam on Aboriginal land was very much intentional and avoidable. This decision underscores the colonialist dynamics that still exist in Canada (and the world) to this day. When Sifton—the real Clifford Sifton was an “aggressive promoter of settlement in the West and a champion of the settlers who displaced the Native population” (Flick 150)—says that he “just builds them,” he uses language that lies beneath an attitude that has justified and made excuses for the mistreatment of First Nations people and their cultures for years. This particular passage seems to be call to action. King is asking us all to evaluate our own role in these injustices.

There are oh so many more, but one can only do so much in so few words!

* * *

“Changing Woman.” Myths and Legends of the World. Myth Encyclopedia, 2014. Web. 18 Jul. 2014.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water.” CanLit 161-162 (1999): 140-172. Web. 17 Jul. 2014.

“Ishmael.” Moby Dick. Schmoop University, 2014. Web. 18 Jul. 2014.

jgordon52. “Call me Ishmael.” Online video clip. Youtube, n.d. Web. 18 Jul. 2014.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

King, Thomas. “I’m not the Indian You had in Mind.” Video. Producer Laura J. Milliken. National Screen Institute. 2007. Web. 17 Jul. 2014.

Witherspoon, Gary. Language and Art in the Navajo Universe. University of Michigan Press. 1997.

Oh Caitlyn, what a wonderful post! Thank you.

I love what you said about Changing Woman and Narcissus. I had recognised the parallel to the myth in King’s narrative, but I hadn’t gone the extra step in my thinking to recognise that he subverts the narrative. It seems obvious now, of course! Changing Woman, as you say, is not punished for her self love, but it is viewed instead as a fertile catalyst for change and growth. Perhaps King’s argument here is that a certain degree of self love is necessary for dynamic change. What do you think?

I also really appreciated what you said about Changing Woman’s embodiment of Ishmael. You point out that it is a name she adopts herself, despite being forbidden to do so, and that, unlike other Ishmaels, she has no need for rescue. The state of perpetual wanderer may have been a prison to some, but King reveals that there is no need to rescue the wanderer when that state of constant motion is a conscious choice and not imposed by others. Perhaps this is also an argument for feminine autonomy, and a rejection of a static (settler?) lifestyle that characterises contemporary North American life. As we know, one of the impacts of colonisation is that Indigenous peoples who had once moved around based on the season and tradition, never settling permanently in one place, were forced to remain in only one place all year around, which effectively killed many important traditions and habits of life.

You mention Eli having “wanted to be a white man” and performing this by teaching in an academic institution. I think it’s really important to recognise that we are studying these texts and engaging in these conversations (aiming, I hope, towards some kind of decolonial perspective) from within an essentially patriarchal and colonial institution. It makes me think of this delightful short story by Heather Harris in which Coyote goes to university to learn about Native Studies, but finds that every course is taught by white people, who get their information from books written by old dead white people. S/he eventually concludes that the only way to hear from Indigenous people is to “quit Native Studies and sign up for the White Studies program!” The humourous part here, of course, is that every course is part of the White Studies program. That’s what colonialism is.

One final thought (sorry this is so long – I got excited): the connection you make between Ahdamn, “Ah, damn!”, and “Ah, dam” links together original sin, dams, and mistakes. The very notion of making a mistake presumes that there is a ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ way to do things. Do you think King is challenging this dichotomy in the text? And does this not also shed some light on Lionel’s situation, he who is so obsessed by his own mistakes? Is Lionel also misinterpreting the idea of a mistake and holding himself back through his inability to let go?

Oops, here’s a link to the Harris story I mentioned. It’s short and quite wonderful: http://row.unbc.ca/v5n1/Prose/HeatherHarris.htm