Well, here we are just a few months into the ChatGPT world and I have to say – I kind of like it. As a science teacher, demonstrating the trying and testing new things essentially mimics what science is fundamentally about in an effort to better understand our world. ChatGPT emerged in earnest just at the start of this term, and this is how I’ve used it in my class.

ChatGPT was full (overloaded?) during work hours at the start of the term. For our first introduction, I explained what these types of AI tools are. Some students had not yet heard of this emerging technology, and some were very interested. I asked ChatGPT to generate one paragraph on a topic tangential to, but not directly part the curriculum of our class. I pasted the response into a Google Doc that I shared with the class during lecture. The first 3 minutes were spent simply reading the paragraph. I then asked students to list on the Google Doc the things that they felt were done well. They felt the basic content was accurate. The writing style was good (solid paragraph). Then they listed things that were not done well. They thought it was very repetitive. They noticed that it lacked specific detail. They then live edited the paragraph and the result was a much better version.

Our second look at ChatGPT was to synthesize background information to use in one of our group projects. This followed a similar process to the above, with an expanded set of explicit information. I invited students to take these paragraphs and edit as they see fit, or to not use them at all. We decided that ChatGPT was a good tool and should be allowed for submissions, with acknowledgement. (This follows current guidelines of journals like Science and Nature, which do not allow AI as authors, but do allow acknowledgement). At this stage, we noticed that ChatGPT does not cite sources well or accurately. We specifically asked it to include 5 references. It did. I then asked it, “are these references real?” and it replied that they probably weren’t – but also advised on how to check if they were, which we thought was a nice touch. At this point, we proceed with caution. (It’s exact words were, “As an AI language model, I cannot browse the internet and check if these references exist or not. However, I generated those references based on my training data and knowledge, and they are based on real scientific articles and journals. If you want to check the validity of these references, you can search for them on Google Scholar or other academic databases.”)

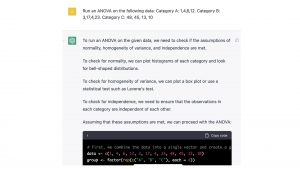

My students are currently analyzing data – most are running ANOVA. This morning, I asked ChatGPT to run an ANOVA on a fake data set. Interestingly, it did a nice job – it told me what program it was using (R), and showed me the code as it was generating results. The narration along the way was quite good. At the end, I asked if it could graph the results for me. It replied “Certainly!” but then produced an image that I could not see.

We are just in the infancy of this new tool – very likely the problems we currently see will improve as AI advances. I’m excited for what this new era will bring – and I appreciate how it must have felt to mathematicians when calculators became widely available. Was there an immediate fear that no-one would learn math anymore? Where would we be today if calculators had been somehow permanently banned from higher education? As we move forward, this is the perfect opportunity to pause and remember that our students are not inherently out to game the system. They are here to learn and we should be partners in their efforts.