For this post I am simply pasting in a email I sent to Dave and my mentor John.

I know, it maybe a bit lazy but it is real life so …

Hi John and Dave,

I hope all is going well.

I thought I would reach out to both of you and maybe you could jumpstart my process on a topic for KIN 530. I knew I was leaving this dangle and I had hoped something would magically land in my sights but nothing yet.

I have now moved back to Calgary and started with the Province as Lead Coach and with Calgary Canoe Club too. My role has a leadership component and I do want to better myself in this area. However, I am not sure this area is the most straight forward for me to use as a project.

I am perhaps more likely to prefer something of a more technical nature where questions and answers are probably more straight forward. One of my mentors, Dr. Larry Holt passed away recently. Dr. Holt was my honours advisor at Dalhousie and who continued to be a great inspiration and influence. He was the first person in my academics who challenged me in a manner that was encouraging. Dr. Holt was the first to work with me in a way that made me want to know what was weak in my work and make me eager to identify it, so to become a better student. When working on some directed studies at Dalhousie, he would encourage me to simplify the question. One question builds one answer at a time.

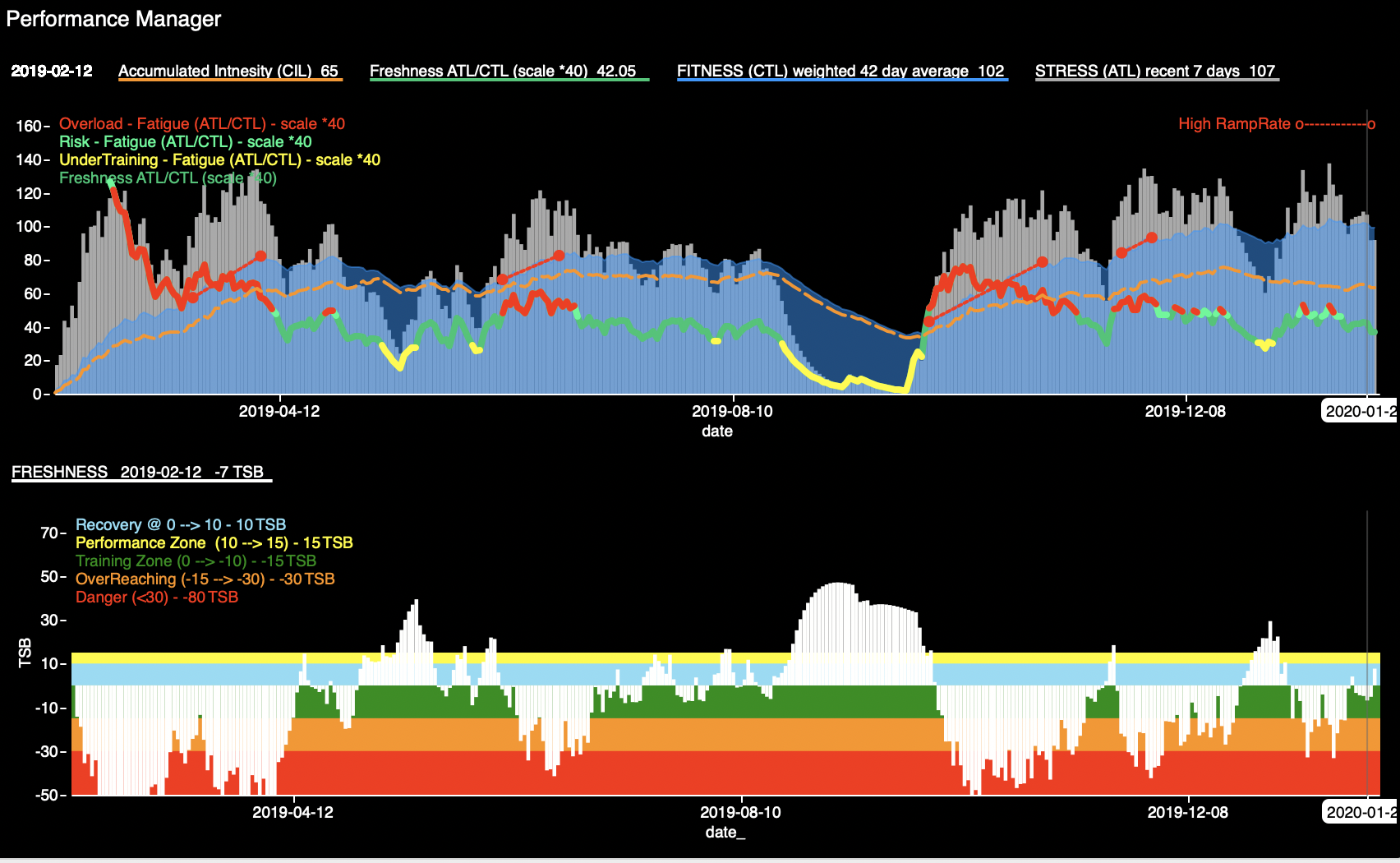

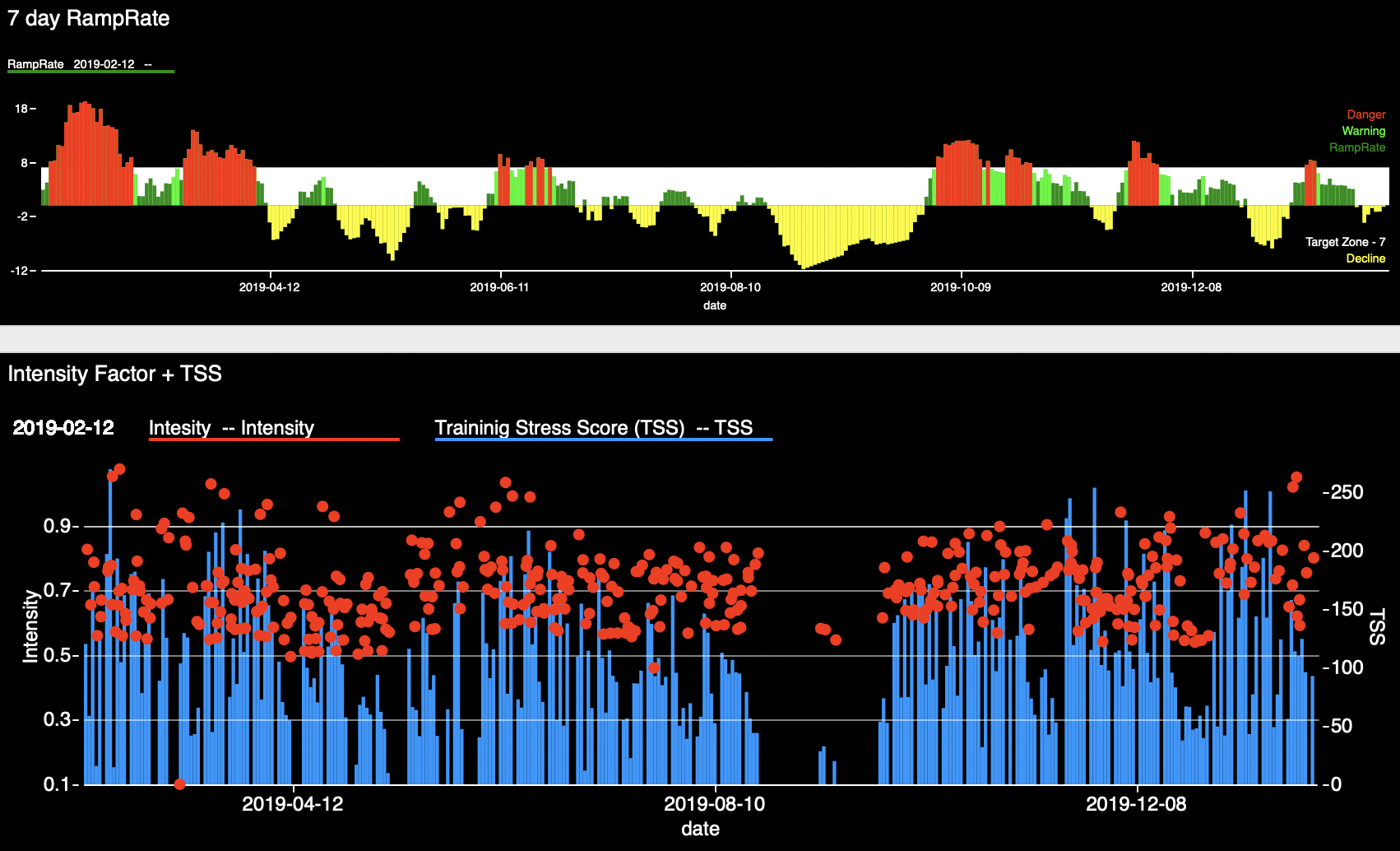

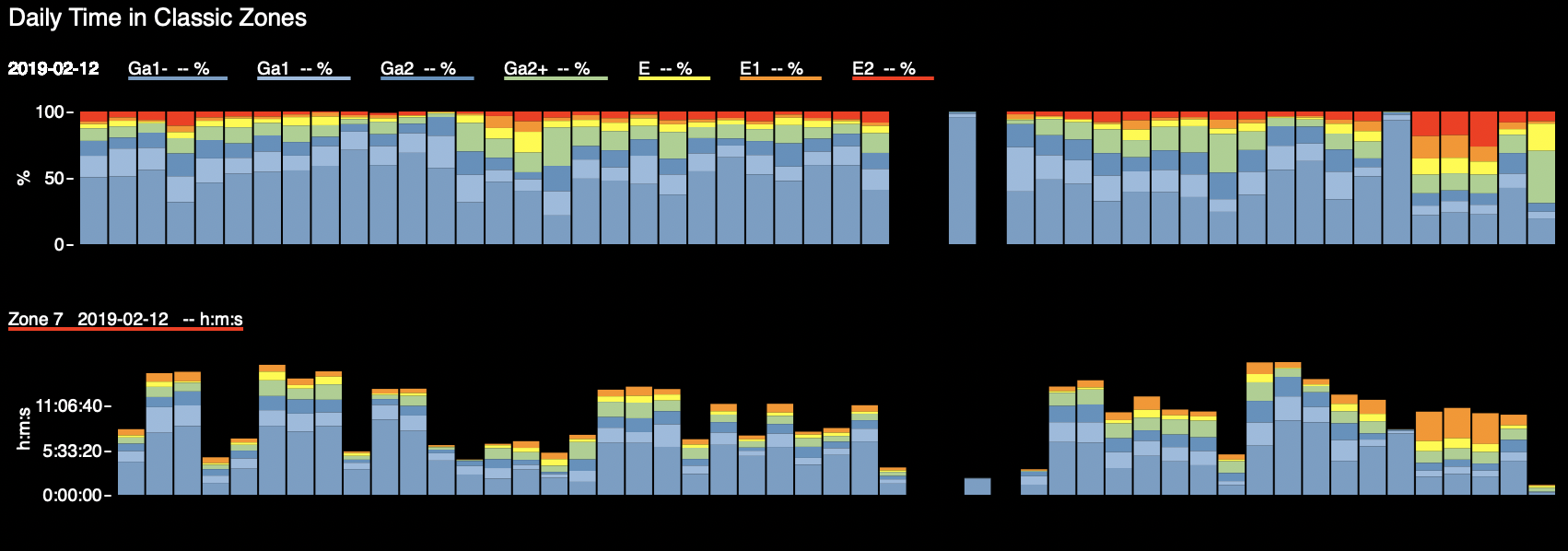

So, for this course I am thinking of Dr. Holt and his advice. I want to ensure my topic is direct and targets a question of interest to my coaching practice. Outside of the area of leadership and in the technical realm the ‘new to me’ things is the information and sessions I have gained from training peaks data. For the past year (nearly) I have collected and watched the training record of one senior athlete. With this process I have realized that although I have a lot of theoretical knowledge, I did not have the information to apply it to programs or to really know how an individual responds to them.

The most simple questions, I realize are not known (openly) in my sport. At least to me and I have a pretty good handle on what the Canadian coaches are doing. I find myself feeling wholly inadequate when reviewing the work coaches in cycling who seem much further along in ‘evidence-based-coaching’. The Canadians coach as though we are writing a theoretical ‘how-to’ coach manual. Everything is sound in theory but very little individualization occurs in the real world and the gap analysis seems to play only a minor role in steering the program away from that for the 50th percentile athlete.

Even in the ’smaller’ senior team groups where the training data could be manageable, it does not seem to be the basis for evaluation or training. There is so much more now for technology to monitor athletes and their response than 10 or 20 years ago. Yet, our coaching remains mostly unchanged. After nearly a year of watching the training peaks data, I find myself wishing I had explored this sooner. A simple example, I was surprised to see that a workout I had been prescribing resulted in twice the workload that I had expected compared to others. Instantly I learned to cut this in half to hav the athlete perform the planned load. Simple things like this, fundamental but straightforward realizations.

Much the the data that is collected raises more questions than answers. I have not found any literature for paddlers but there is so much on cyclists who have been using this information for a couple decades now. The introduction to training with power on the bike has now become the norm and there is a vast amount of data and the elements the lead to top performance, overreacng and under training. I can use this information and generalize to my sport in some cases but in others I done know if the numbers are good or bad.

One athlete I am monitoring has a critical training load (CTL) that has reached about 100 (Training stress score). The CTL is a weighted rolling average of the past 42 days and equates roughly to level of fitness. Last season the max value was about 80 so now is already ~25% higher than last season and a significant increase. Fitness is good, but how much is needed? When is too much? Is there too much? So a simple question, what is a typical world class CTL range for a performer in this sport? I can read that a Tour de France rider may perform well at a value of 130-150 but is this true for a paddler who races under 2 min? What do I advise this athlete? How do I make comments ‘evidence based’.

This is just one simple example and one simple question that I have no answer for (I have many others). But the answer would be a powerful bit of knowledge for the coach and athlete (– if anyone has an answer, give me a call –). If I was collecting data on our team for a few years I may learn this. If I collect data on this one athlete for another year I may start to learn this, ‘for this paddler’.

So I wonder, is there a straight forward way to answer just one question relating to all this extra info I am watching and the questions it creates. Would a topic in this more technical area of monitoring be suited for my directed study in KIN 530?

Posted below are some screen grabs of the data I have been watching for the past 10 months. These will open to larger version if clicked on or if you select to open in a separate window.

Hmmmm…. OK, I leave this email at this point and wait to see if you have comments. Basically, just looking to engage in some conversation that will help me set a direction and get going on a project.