Beijing’s bid for the 2022 Winter Olympics relied solely on covering their cold-but-dry mountain venues, Yangqing and Zhangjiakou, with 100% artificial snow.

Snow machines were essential to Beijing’s Olympic bid (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

For every cubic meter of snow produced, half a cubic meter of water was required, raising concerns about Beijing’s bid.

Clean water is a scarcity in the northern region around Beijing and within the city itself. The region pumps in 70% of its water from southern China.

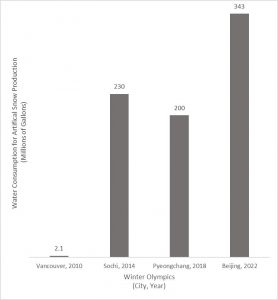

In their bid, Beijing estimated 49 million gallons of water would be needed to maintain the slopes, but, in reality, 343 million gallons were turned into snow.

Snow machines mix and cool compressed air and water, releasing tiny balls of ice onto the slopes and compacting four times denser than natural snow.

The presence of artificial snow has increased in the Winter Olympics. Artificial snow made up 80% of Sochi’s snow, 90% of Pyeongchang’s snow, and 100% of Beijing’s snow.

Figure 1. Water consumption estimates for artificial snow production at the past four Winter Olympics

In 1980, Lake Placid was the first Olympic venue to use artificial snow, but troubles with lack of snowfall are a recurring theme. In 1964, Austrian soldiers hauled 20,000 blocks of ice to prevent cancellation of the winter games. Vancouver, in addition to snow machines, transported snow with semi-trucks from higher to lower elevations of Cypress mountain.

Cross-country skier competing at the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Skiers expressed concerns over artificial snow courses. The snow’s closer packing allows faster ski times but increases the likelihood of collisions. Athletes crash on snow that “feels like concrete”. In turn, the density allows for easy construction of ski and snowboard ramps.

A study found that, with global temperatures rising, only one of the past 21 Winter Olympic venues, would be able to provide natural snow by the 2080 games.

To keep the global athletic competition alive, fake snow will be the way to go.

-Julia Sawitsky