Photo 1. Infographic of the role of the ocean. Licensed for reuse. Source.

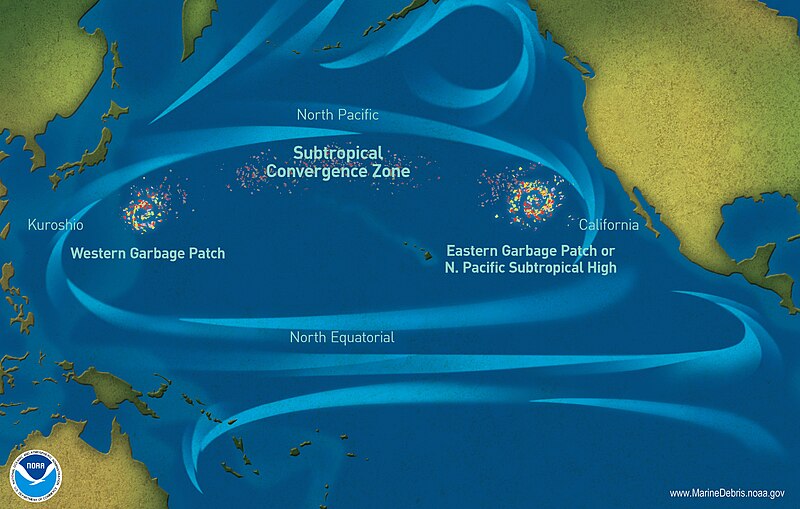

The ocean, which covers 70% of the Earth’s surface, plays an important role in our everyday lives. It provides the oxygen we breathe, feeds us, and regulates our climate (Photo 1). It serves as a mode of transportation across the world and also provides an opportunity for recreational activities. However, it was found that that much of the ocean is now seriously deteriorated due to human impact. This impact is projected to increase as the human population continues to grow every year. Therefore, science-informed policies and strategies need to be implemented to protect the oceans are urgently needed.

Goal 14 and The Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development

In order to address this issue, in 2015, the UN published the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) which included an ocean-specific goal. Goal 14: Life Below Water states “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”. To meet this goal, the UN has announced a Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030) in hopes to mitigate the negative impacts on the ocean by gathering ocean stakeholders worldwide to come up with a scientifically supported framework to improve ocean health.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=12&v=YyiuLwhUpH4

The video above discusses the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development

One Planet, One Ocean: Mobilizing Science to #SaveOur Ocean. Source.

At this event, multiple ocean communities from across the world come together to plan for the next ten years in ocean science and technology to make our ocean more sustainable. In May 2019, there will be a first global planning meeting where stakeholders from the world gather to discuss and investigate tangible actions and framework to meet the Decade’s objectives. This serves as a crucial introduction to creating a global dialogue towards sustainable ocean management.

For the keen learners out there, check out the podcast below, where you will further understand how the “blue economy” and “marine social sciences” are promoting sustainable management of oceans around the world.

The audio clip above is an episode of the world-famous podcast “Ask Juanonymously”

SO Project – Group 1. Source.

Canada’s Progress So Far

The statistics show that since the implementation of this policy, there have been positive steps to achieve Goal 14, through the expansion of protected areas for marine biodiversity and an increase in ocean science funding to preserve marine resources. However, an increase in education and awareness will assist in accomplishing Goal 14 at a much faster rate. As Vancouver residents are surrounded by coastal communities, it is crucial that we gain an understanding of the importance of protecting the ocean, through adopting sustainable habits. Take a look at the video below to learn more about how to maintain the one ocean that unites the nations together.

The video above outlines the importance of sustainable ocean management, including how YOU can play your part.

SO Project – Group 1. Source.

Written by: Suyoung Ahn, Christina Kim, Juan Gomez