Human behaviour is often neglected in the design of our urban systems, simply due to its complexity. New and emerging research is now focusing on how behavioural decision-making can be linked to our environmental needs. For recycling and consumption of products, it is important to consider them as behaviours, such as healthy eating and exercise; while we know those behaviours are good for us, we may not always behave that way due to numerous psychological reasons.

So how effective is it to truly consider psychology in design? In a study called “It Matters a Hole Lot”, changing the shape of the recycling container lid, increased correct recycling by 34%, allowing for less contamination in waste streams. This shows that visually manipulating the users’ behaviours educates and also enforces correct behaviours.

Researchers at UBC experimented in residential buildings on how the distance to recycling and composting bins can affect the volume recycled. Results showed that conveniently placing the recycling bins 1.5 meters away from residence doors can increase recycling up to 141%. The same researchers state that education is a traditional mechanism on increasing recycling and composting, instead, they believe that convenience has been observed to be of a much larger impact as observed in their study.

In contrast, the availability of recycling services can enable people to produce more waste and affect their behaviour, as a consumer, knowing that it can be recycled later on. The act of recycling does not guarantee that recyclables will not end up in the landfill and thus must be our last resort. In Recycling Gone Bad, researchers determined that recycling behaviour is linked to the rebound effect, defined as the reduced costs accompanying technological improvements in efficiency may have the unintended consequence of increasing consumer demand. An example of the rebound effect: the recycling symbol, invented by the beverage industry, may encourage the consumption of these beverages as it removes the guilt linked to increased consumption.

It is important to focus on reducing waste overall and not invest all of our recourses in proper recycling. Throw-away culture has enabled a behaviour of purchasing goods that exceed our needs and often end up as waste. While recycling is critical to a closed-loop economy, behavioural changes must be considered. In order to break the throw-away culture cycle, one must adopt the first R of the 5R’s pledge. Refusing samples, gifts, plastics bags, etc. instead of accepting them simply because they are free, will allow us to overcome our culture that is not able to say no. Our society must become comfortable saying no – if a gift is of no use to you, refuse it. Acquiring a lesser amount of belongings will lower the demand for their production and inevitably divert them from our landfills.

Next time you are at a conference, take a look around you and count how many tote bags, full of brochures, will end up at our landfill. In the United States, the promotional products industry is estimated to be $24 billion. If companies are looking for their attendees to remember the conference long after, they could invest in the experience as opposed to free swag. A good meal, at a conference, goes way farther and shows the company’s commitment to the quality of the conference.

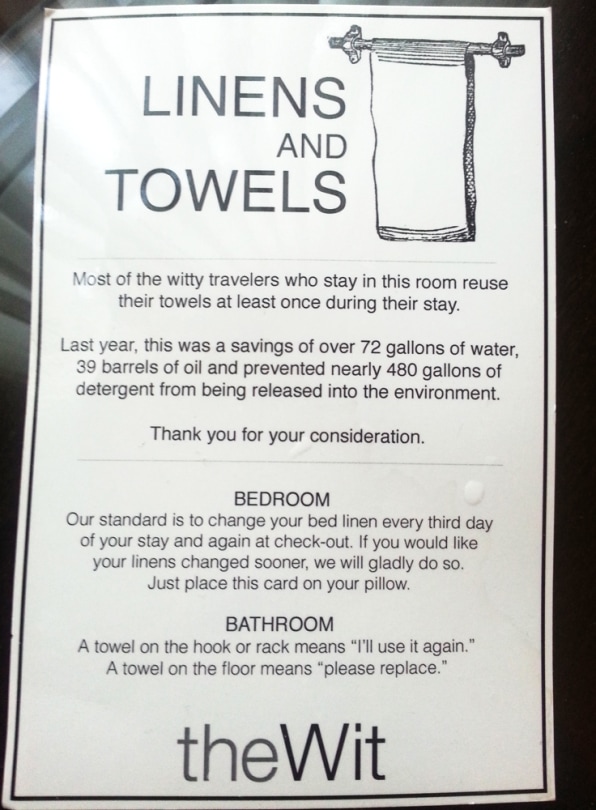

But what if we changed people’s behaviour to use less? A study from the University of Arizona discovered through their experiment that utilizing people’s desire to “fit in” can also influence their behavioural decision making. When hotel guests were informed through signage (as shown below) that previous guests, in the same room, have reused their towels, it allowed for a 33% increase in towel reuse.

Strategic changes to people’s unsustainable consumption must understand habitual behaviour. Habitual behaviour is ingrained and automatic to situational cues and often proves many interventions as ineffective. One area that is being explored in intervening unsustainable behaviour is nudge theory, which uses “positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions as ways to influence the behaviour and decision making of groups or individuals.” Nudge theory is seen here at the University of British Columbia, where a 25-cent levy was introduced on non-reusable cups to gently encourage consumers to bring their own cups. Is 25-cents enough to influence someone’s behaviour in this day and age? This remains a topic of controversy in many settings where a levy was introduced.

The amount of tax imposed on single-use plastics has been highly controversial, throughout the world, and not many nations have been successfully able to phase out plastic bag usage using a tax system. Although, Ireland has been a great leader on this front:

In 2002 Ireland became the first country to impose a plastic bag levy. It led to a 90% drop in use of plastic bags, with one billion fewer bags used, and it generated $9.6 million for a green fund supporting environmental projects. In addition there is much less roadside litter from plastic bags. Ironically, with the success of the program, and people bringing their own reusable carriers to shop, the proceeds from the levy have fallen and there is less money for supporting environmental projects.

As for today’s designers & engineers, it is important to consider the behaviour of users we are designing for. Nudge theory can be applied to less energy usage in buildings, less water usage and less plastic consumption. Psychology is applicable to all fields of design in which humans are involved. Ignoring the ways humans behave is simply foolish and a waste of our resources at such a critical time of our environmental crisis. Educating consumers remains to be insufficient for altering decisions and intentions are often not reflective of behaviours.