The Ottawa Occupiers represent a stratum of the capitalist class that has always found itself in a middle ground in antagonistic relationships with both corporate capital and organized labour. Don’t be confused by the trucks – these men (and they are mostly men) and women don’t really drive trucks all the time. Typically, they’re operating modest businesses that are essentially yoked to larger industrial firms.

Scenes from the Ottawa Occupiers showing their colours.

My own family network includes some of these folks. Hard working, opinionated, and often filled with a jaundiced sense of us educated white collar workers who ‘don’t really know how to work.’ They are constantly doing deals, getting contracts, and cursing the overreach of government into their profits. They’re pissed at the slick lawyers who work for their corporate clients. They often think of their own employees as family and friends. This fragment of the capitalist class has tied itself to a nativist economic and political agenda.

This is a segment of the capitalist class that has played a disproportionate role in shaping Canada’s (colonial) history. In the early 1900s, for example, this stratum organized a 1912 agreement between Victoria and Ottawa to create and protect an all-white sector in BC’s commercial fishing industry (for details check my paper on the foundation to BC’s industrial economy). The men who ran small business in fisheries had control of the Victoria legislature. They used this power to try and gain a foothold against the big capital of Henry Bell-Irving on one side, successful ethnic Japanese firms on the other, and effective indigenous fishers on the third. The legacy of their desire to remove Indigenous and Asian participants from the fishery still reverberates in actions their descendants are involved in today.

The deployment of the Canadian flag figures large in all the various truck rallies and occupations underway in Ottawa and across the country. Also prominent are calls for freedom. The invocation of these two symbols underlies the current form of capitalism the Ottawa Occupiers are promoting. It’s a kind of capitalism that links nativism – defense of the local born ahead of more recent immigrants- with an abstract idea of freedom (primarily understood as free choice, see Milton Friedman’s book Capitalism and Freedom for elaboration), and a conservative white settler nationalism (rooted in a US sensibility of patriotism and flag waving).

There is a certain irony in the fact the Canadian right initially protested the red maple leaf as the national flag, in preference to the British Red Ensign and Union Jack. The new flag was called divisive, it was said it would undermine unity, and that it was a disrespectful attack against Britain, Canada’s war time ally and colonial homeland. Yet today, socially conservative forces have wrapped themselves in this new symbol claiming it as a marker of a nativist settler Canada based on a neo-liberal concept of freedom.

These same protesters are pointing to the Canadian Charter of rights (an act of parliament that was also soundly criticized by the conservative forces of the day in the 1980s). It was the elder Trudeau who brought in the Charter of Rights, called communistic by his oil conservative opposition with very much the same language as is being used against Justin Trudeau today. Say what one might about the obvious connections between mainstream parties of the center and right, but neither Trudeau is a communist in any true sense of the word.

The Ottawa occupiers are firmly rooted in a pro-capitalist discourse. Their use of symbols might be opportunistic, but the underlying nativist and white supremacist theory is deep rooted and persistent across this stratum of the capitalist class and is furthermore anchored in the development of Canada’s settler capitalist economy.

I’m going to turn to two seemingly unconnected examples – The Supreme Court of Canada’s Kapp Decision (a fishing rights case) and the rise of the Eastern Metis. Both examples share references with the alt-right occupiers in Ottawa and can be understood as laying down some of the conceptual framework that motivates the Ottawa occupiers’ sense of entitlement and ownership.

The Kapp Decision involved a group of mostly white fishermen who fished in protest of an aboriginal pilot sales fishery in the 1990s. They claimed that the aboriginal fishery violated the charter of rights and was discriminatory to white fishermen and their ethnic allies. To make their case they essentially mounted an argument that asserted the white fishermen, and their ethnic allies, were ‘indigenous’ to BC. They used the same kind of evidence required for an aboriginal rights & title case. In the court proceedings their lawyer, Chris Harvey (notable for many anti-Indigenous court case and interventions he was involved in during the 1980s and 1990s) led evidence that supported the claim white fishermen, and their ethnic allies, were an inherent cultural community with rights derived from their longstanding (two to four generations) communities of practice. The supreme court ultimately rejected their claim and decided that the pilot sales fishery was legal under the provisions of the charter of rights. The critical point here is the way this group of white commercial fishermen positioned themselves as having an inherent, land-based, and culturally distinct right as an indigenous-like people. Unlike the Eastern Metis, they did not engage in race-shifting (white people claiming a trans-racial identity), but they did assert a right based in a conceptual frame that mirrored the legal test to establish aboriginal rights and title.

White Supremacist Pat King filming eastern metis group performing at Ottawa Occupation theatre.

The rise of Eastern Metis is a phenomena academic Darryl Leroux has been writing about. His book, Distorted Descent, is a detailed study of how white Quebecers and Maritimers have reconstructed their social identity via race shifting from white to metis based upon an ancient genealogical link. In the article Self Made Metis he documents how a group originally created as a white hunters’ rights group transformed into one of the first eastern metis associations. What is instructive here, like with the Kapp Decision, is how a white group in conflict with Indigenous rights and title reconfigure themselves as more authentically deserving and entitled than either recent immigrants or actual Indigenous peoples – both groups seen as having special undeserved rights.

All of these movements are linked to an appropriation of belonging. The preferred groups (white men and their female and ethnic allies) feel they have a preferential sense of rights and belonging that entitles them to a special place in Canada. But it is more than that; it is also a type of capitalist ideology that affirms their sense of prioritized place and rights within Canada. This is a kind of capitalism that contributes to the displacement and usurpation of Indigenous rights. It also echoes older euro-centric ideologies of racial supremacy. It is not, however, an aberration. It is part and parcel of Canada’s settler capitalism and culture of expropriation and appropriation of Indigenous land, waters, and culture.

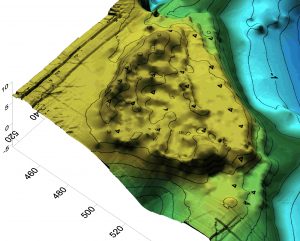

When we scrape off the foundation materials placed on the ground at Citeyats we find a wet swampy lower elevation site not really suitable for human habitation on the long haul. But the Citeyats we know today is dry, elevated, and set above the water level in ways that create a prime place for people.

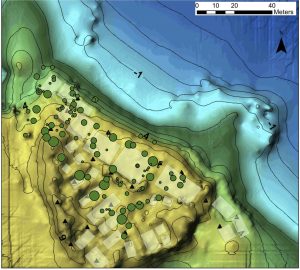

When we scrape off the foundation materials placed on the ground at Citeyats we find a wet swampy lower elevation site not really suitable for human habitation on the long haul. But the Citeyats we know today is dry, elevated, and set above the water level in ways that create a prime place for people. The Green dots on the map represent trees; the bigger the dot, the older the tree.

The Green dots on the map represent trees; the bigger the dot, the older the tree.