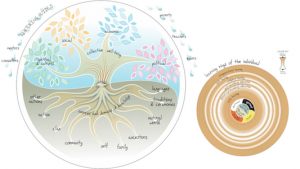

The First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model “represents the link between First Nations lifelong learning and community well-being, and can be used as a framework for measuring success in lifelong learning.”

A living tree is the symbol that represents the process of holistic lifelong learning. The tree encompasses the different cycles and elements upon which individual learning experiences are based. The well-being of the community depends on these individual learning experiences.

According to the model, holistic learning occurs through a circular activity where everything is interconnected (as opposed to the classic “linear” theory of learning based on cause-effect dynamics): Learning is formed through language, tradition, nature, family, elders, ancestors, community, etc. All these elements are interdependent and the absence of one element would destabilize the whole learning process.

The trunk of the tree represents the linking segment that connects Indigenous knowledge with Western knowledge. The core of the trunk is made of a series of rings that symbolize individual development: spiritual, emotional, physical and mental. The rings symbolize the continuity of learning that starts at birth and continues throughout life.

Source: http://www.ccl-cca.ca/CCL/Reports/RedefiningSuccessInAboriginalLearning/index.html