The Scroll and the Codex

In the Oxford forum, From Papyrus to Cyberspace, O’Donnell provides a brief history of the birth of the codex. Even though O’Donnell’s summary of the codex was a short segment of the much longer discussion, I found the piece fascinating and some further research uncovered some of the complexities of the topic of one technology replacing another.

The bound pages of the codex were the earliest form of the modern book and the technology gradually replaced the scroll. The success of the scroll is a historical mystery. O’Donnell explains that early Christians were early to adopt the technology and historians are not sure why. Several theories have been discussed and refuted. O’Donnell dismisses the theory that the codex’s ability to easily lookup passages could have been a factor because page numbers did not become a part of the technology until much later. Larry Hurtado discusses his book The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins on his blog and refutes several other claims that relate to the proposed advantages of the technology.

Hurtado explains that the materials and construction of the codex did not make the technology cheaper than the scroll, refuting the theory that Christians were looking to save resources. The author also explains that portability was not an advantage either, both the scroll and the codex came in miniature versions that could have served similar functions. The Christians use of a variety of texts as scriptures was also theorized as a trait that could have favoured the codex, however, Hurtado explains that again, the ability of a codex to string together multiple texts did not arrived until much later and could not have been a factor in its first success. The author admits that despite little evidence, the best theory is that the new technology was favoured because it could distinguish its users from others. Early Christians produced a variety of texts using both technologies but specifically focused on using the codex for their own scriptures; this suggests that the motivation for using the new technology was to create texts that were easily distinguishable from Jewish and Pagan texts which were found on scrolls.

O’Donnell and Hurtado’s description of the transition from scroll to codex raises many questions about the adoption of a new technology which did not appear to have a clear functional advantage over the old. Although each historian explains that the reason why the Christians adopted the codex is unclear, I feel that the conclusions may be a little too dismissive regarding possible technological advantages. Even without page numbers, wouldn’t locating passages be easier with a codex than a scroll? Also, if the immediate functionality of the codex was not significantly advantageous, could early Christians have recognized the potential of the technology and find motivation in its long term potential? Despite refuting theories which focus on the functionality of the technology, alternative theories which focus on the social and political environment of the time are limited. Hurtado suggests the possible desire of Christians to distinguish their texts from others but does not investigate this question further. In the early days of the codex, roughly 200 AD (O’Donnell, 1999), Christians were still actively persecuted, couldn’t distinguishing the community of Christians by using the codex create some risk? The mystery of the shift from scroll to codex highlights the complex relationships between technology, economics, society, and politics, narrowing down motivations behind technological change could prove difficult when studying present day examples, let alone historical examples with limited evidence.

References

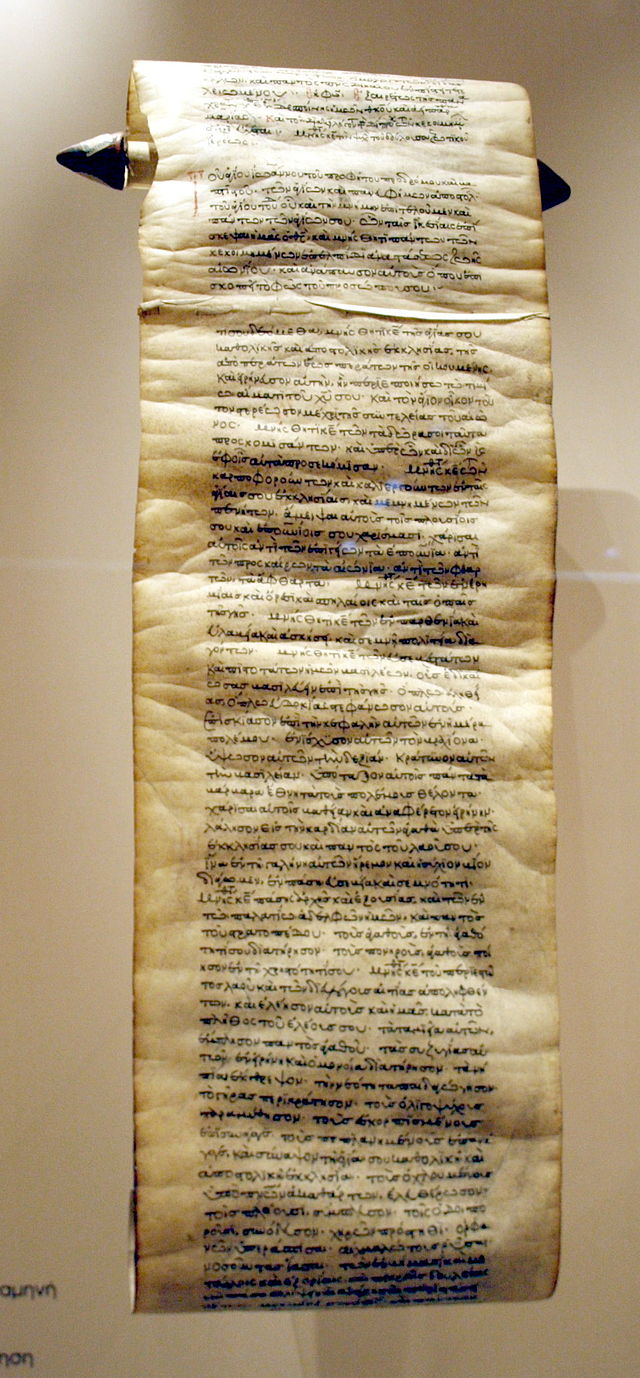

“Byzantine Museum, Athens – Parchement scroll, 13th century – Photo by Giovanni Dall’Orto, Nov 12″ by G.dallorto – Own work. Licensed under Attribution via Wikimedia Commons – http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:2049_-_Byzantine_Museum,_Athens_-_Parchement_scroll,_13th_century_-_Photo_by_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto,_Nov_12.jpg#/media/File:2049_-_Byzantine_Museum,_Athens_-_Parchement_scroll,_13th_century_-_Photo_by_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto,_Nov_12.jpg

Cambridge Forum. (1999). From Papyrus to Cyberspace

Hurtado, L. (2013, August 1). Early Christians & the Codex: A Correction/Clarification (Web Log Post). Retrieved From https://larryhurtado.wordpress.com/2013/08/01/early-christians-the-codex-a-correctionclarification/

Persecution of Christians. In Wikipedia. Retreived May 20, 2015 from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Persecution_of_Christians

Hi Brendan,

Great insights, and I agree with your statement that “O’Donnell and Hurtado’s description of the transition from scroll to codex raises many questions about the adoption of a new technology which did not appear to have a clear functional advantage over the old”. Just an add-on to your argument: Even that we have supposedly passed from those print-oriented technologies (scroll and codex), we have not been able to find more suitable metaphors for navigation within a website, we are still scrolling and paging, right? In fact, after who knows how many years, we are still talking about that:

http://hfs.sagepub.com/content/25/3/279.short

http://jssam.oxfordjournals.org/content/2/4/498.short

Hi Ernesto and Brendan,

What a great point about the scrolling and paging. Just another thought, even in an eReader, the motion we use to “turn pages” is a replication of print-based technology.

-Ronaye

Hi Brendan –

Your summary was succinct and thorough. Once listening to the program, it gave me a better understanding of the major points O’Donnell was trying to get across.

Thank you,

Bre

The distinction made between the scroll and the codex was one I never really considered before. It strikes me as a question of interface. It is interesting that we are still scrolling and paging but I think the real modern analogy is that we now “Google” or use another search engine.

While the codex might not have been created to improve the ability to search, we can see that it is an advantage of that form of information organization. Today we are faced with the problem of too much information. Eric Schmidt of Google stated in 2010 that “There [were] 5 exabytes of information created between the dawn of civilization through 2003, but that much information is now created every 2 days, and the pace is increasing.” The veracity of his claim is debated but it is clear that we have more information than ever and that sifting through it is becoming an ever greater endeavour. It is not enough to publish anymore. One must be able to distribute what they have created find the information they are seeking.

Brendan raised some good questions about the reasons behind the adoption of the codex over the scroll. If it wasn’t cheaper or more practical at the time, then why did it catch on? Perhaps further research will reveal a plausible theory. In the meantime I fear the answer is something as banal as humanity’s own capricious love of novelty.

http://readwrite.com/2010/08/04/google_ceo_schmidt_people_arent_ready_for_the_tech

“Christians were still actively persecuted” so maybe the inventor was looking at the shape of the scroll versus codex. Small tiny flat volumes could be hidden in clothing, hidden compartments in wooden boxes. And it could be that the original purpose of the codex had nothing to do with replacing scrolls.

Food for thought

Terry

Thanks for sharing that image of the parchment scroll.