Communication on the Continuum

Communication on the Continuum

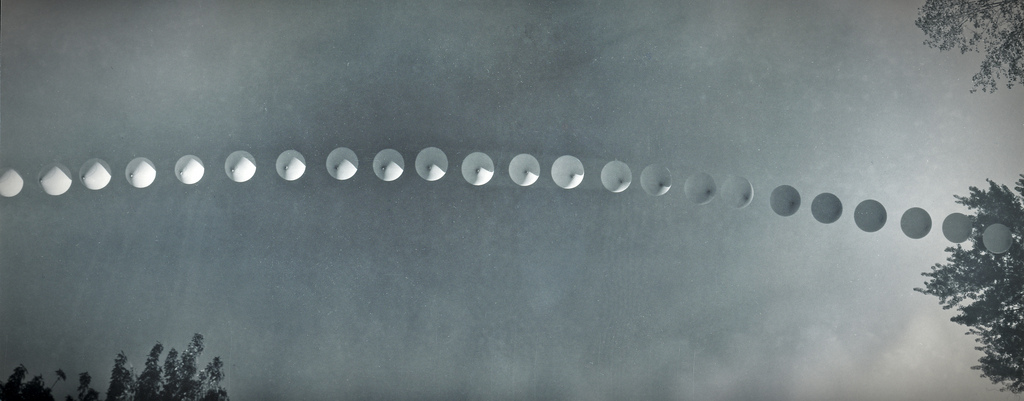

Ong (1982), in his work on orality and literacy, has developed a list of contrasting characteristics of oral and literate societies by looking at historical examples of texts produced by an oral society, or by societies with a high oral residue. He presents these contrasts as evidence that human thought processes are restructured by the technology of writing. However, Ong also provides examples to show that when writing is introduced to or developed by an oral society, the transition to fully interiorized literacy isn’t immediate or inevitable, and the society may produce written texts that carry a vestigial residue of its oral past. In this way, there is not a divide, but rather a continuum between orality and literacy, although societies and individuals on the extremes of the continuum find it difficult or impossible to understand the thought and expressions of those at the opposite pole.

Ong doesn’t identify a pressure that moves societies along the continuum from orality to literacy, and finds both strengths and weaknesses in the communication techniques used at either end. Indeed, Chandler (1994) says that Ong is phonocentric, with a bias towards seeing orality as belonging to a natural, idealized past and literacy as artificial and dead. Gaur (1992), in her work on the history of writing, tells us that “each society stores the information essential to its survival, the information which enables it to function effectively.“ This observation also applies to oral cultures, and Ong (1982) has described some of the techniques that oral societies have developed for organizing and communicating knowledge to fulfil their needs. When writing is developed or introduced in a society, this new technique of communication makes possible new modes of thought and expression that oral communication can’t support, but the transition to full literacy may be gradual or incomplete.

Ong’s phonocentrism contrasts with the graphocentrism (Chandler, 1994) that is more common in Western education systems. Graphocentrism values written communication more highly than spoken, and equates movement along the continuum from orality (pre-literacy) to literacy with progress.

Implications in the classroom

Ong’s theory that writing restructures consciousness has been criticized as being deterministic (Biakolo, 1999; Chandler, 1995). However, there is value in Ong’s description of the strengths of the oral and literate modes of communication, and we can apply his ideas to the secondary school classroom without having to decide on the validity of his theory.

Each student has characteristics that Ong ascribes to oral and literate mindsets, and the dominance of those characteristics varies depending on the individual student, their development and the environment they are in at a particular time. We can expect that our classroom, at any time, contains students in a variety of positions on the orality/literacy continuum. Teaching should play to a student’s strength in order to be most effective; however we have to recognize that students don’t remain at a static point on the continuum but rather that their positions can change depending on a number of factors.

We need to recognize, and encourage our students to recognize, that there is value in the modes of thinking and expression at both ends of the continuum and at intermediate points. The goal of education is not to simply move students along the continuum but to help them develop a range of skills across the continuum.

References

Biakolo, E. A. (1999). On the theoretical foundations of orality and literacy. Research in African Literatures, 30(2), 42-65.

Chandler, D. (1994). Biases of the Ear and Eye: “Great Divide” Theories, Phonocentrism, Graphocentrism & Logocentrism [Online]. Retrieved, 31 May, 2015 from: http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/litoral/litoral.html

Chandler, D. (1995). Technological or Media Determinism [Online]. Retrieved, 31 May, 2015 from http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/tecdet/tecdet.html

Gaur, Albertine. (1992). A history of writing [revised edition]. London: The British Library.

Ong, Walter J.. (2003). Orality and Literacy. Routledge. Retrieved 31 May 2015, from <http://www.myilibrary.com?ID=1960>

Janice I so appreciated reading your post. It helped me understand some ideas that I hadn’t been able piece together or organize in my mind yet.

The implications for the classroom really gave me something to think about. As a Literacy Support teacher, a lot of professional development in our division has been structured around the idea that students need the opportunity to write in all subject areas. This helps them make sense of and process information as well as making sure writing is an ‘activity’ that happens only in ELA. I believe that if we leave any form of communication – writing, speaking, reading, etc. – off the table, or off of the continuum, we are not meeting the needs of our students/learners. A critical piece of the learning puzzle is missing if we focus on any one form of communication. With that said, how we balance all modes of communication?

Ong made some excellent points regarding primarily oral cultures that gave me a lot to think about including the lack of need for definitions, and being aggregative rather than analytical. However the most meaningful ideas occurred to me when I connected Ong’s ideas to the classroom. I think it is so important to balance written and oral language in the classroom. Each student that walks through the door, learns in a different way. It is important that in planning, teaching, and assessing, all learning styles, modes and methods of communication are acknowledged and appreciated. Therefore, all students learn in the most meaningful, efficient way.

Really great post Janice,

I completely agree that we need to consider the strengths and weaknesses in oral and written communication. However, I’m not sure I agree with Ong’s (1982) characterization of the orality/literacy continuum as a progression for individuals. In the past, oral language seems like prerequisite for written language. Thought changes as a product and the culture of a society becomes transformed through the use a written language. They internalize the act of writing as ways of thinking.

With individuals, I’m not sure the same process exists. I would definitely agree that students develop certain thinking skills by developing their literacy. Logical syllogisms are definitely a product of literate thinking. However, the categorization of tools that Ong discusses with reference to Luria’s research doesn’t seem to require literacy to be taught. Rather it’s a cultural by-product of a literate society. We teach our children to group objects by abstract categories before they can even write.

Likewise, we also need to teach our students to improve their oral language skills. Using speed and tone properly are really important in public speech and storytelling. Most students, rather than being naturals find oral language skills to be quite difficult. They need to taught to practice what would have been culturally common in preliterate societies like Dark Ages Greece, Early Northern Europe, or tribal societies in the Amazon, Sub-Saharan Africa or New Guinea.

So I completely agree with Allison that we need to balance and strengthen both sets of skills when teaching through a wide range of activities that require use of orality and literacy.

Ong. Walter. (1982). Orality and Literacy. New York: Methuen.