Orality, Literacy: Experiencing the Oral World from Multiplication Tables, to Macbeth, to the Strike…

Is rote learning of any use in literate cultures with easy and affordable access to various methods of information storage?

I think the easiest way to begin my response to this question is to relate my own experiences from when I was a child. I actually enjoyed the rote learning nature that I experienced in my elementary and high school life. I loved the multiplication table rote learning we did as well as the conjugation of verbs in French (nerd?). My teachers used games to help us remember and I know that it made math and speaking in French much easier later on because time was not used on simple computations or trying to remember the proper verb form. Perhaps it was too far back in my memory, but I don’t recall being overly stressed out or hard done by learning in this manner. Fast forward to high school and really the only rote learning that I can recall was when I was forced to memorize Shakespeare. As an English teacher today, for some reason, I do not force my students to do this, but it didn’t appear to hurt me then, so why am I afraid to do it now? As for my Shakespeare, I tend to freak out the students when I can still deliver the ‘dagger’ speech from Macbeth. Was there value in having memorized it nearly 25 years ago? This remains to be seen.

As I was reading Orality and Literacy by Walter J. Ong, a thought came to mind. First, with respect to my experience with memorizing the Shakespeare passage, I can now see why it was actually relatively easy to do and why I can still remember it after all these years. Furthermore, Shakespeare’s works were meant to be performed as oral and dramatic texts. They were created to be heard, not to be read. Shakespeare writes in a specific pattern (iambic pentameter). Therefore, when Ong discusses the mechanics of oral culture that aid in remembering the “memorable thoughts,” I was immediately reminded of my experiences. Things such as, “rhythmic, balanced patterns, in repetition or antitheses, in alliterations and assonances” (p. 34) aid “so that they come to mind readily and which themselves are patterned for retention and ready recall.” Since my memorization of the speech was in fact an oral task meant to be heard, these methods actually made it much easier for me to do so. But now as an English teacher, I’m not sure I can see value in memorizing that speech (other than a simple task in being disciplined) as we can easily look up that speech and interpret and analyze as required.

As for the math experience, since I am not a math teacher, I cannot really say with authority whether or not there is value in memorizing the multiplication table, for example. I know that for me personally, I see students needlessly wasting time using a calculator to do (what I deem) simple math calculations. Perhaps if the students knew the answer by rote, they could focus on other more complex tasks.

The closest I can come today to experiencing a challenge with rote learning is with my Geography students. We are currently having a major debate between the grade 7, 8 and 9 Geography teachers over whether or not the students should know the provinces, territories and their capital cities. I say they should because it makes other tasks that much easier.

Others say, they can Google that. I say why Google when you can already know this? There is a time and a place for inquiry, but do we really need to look up the provinces every time?

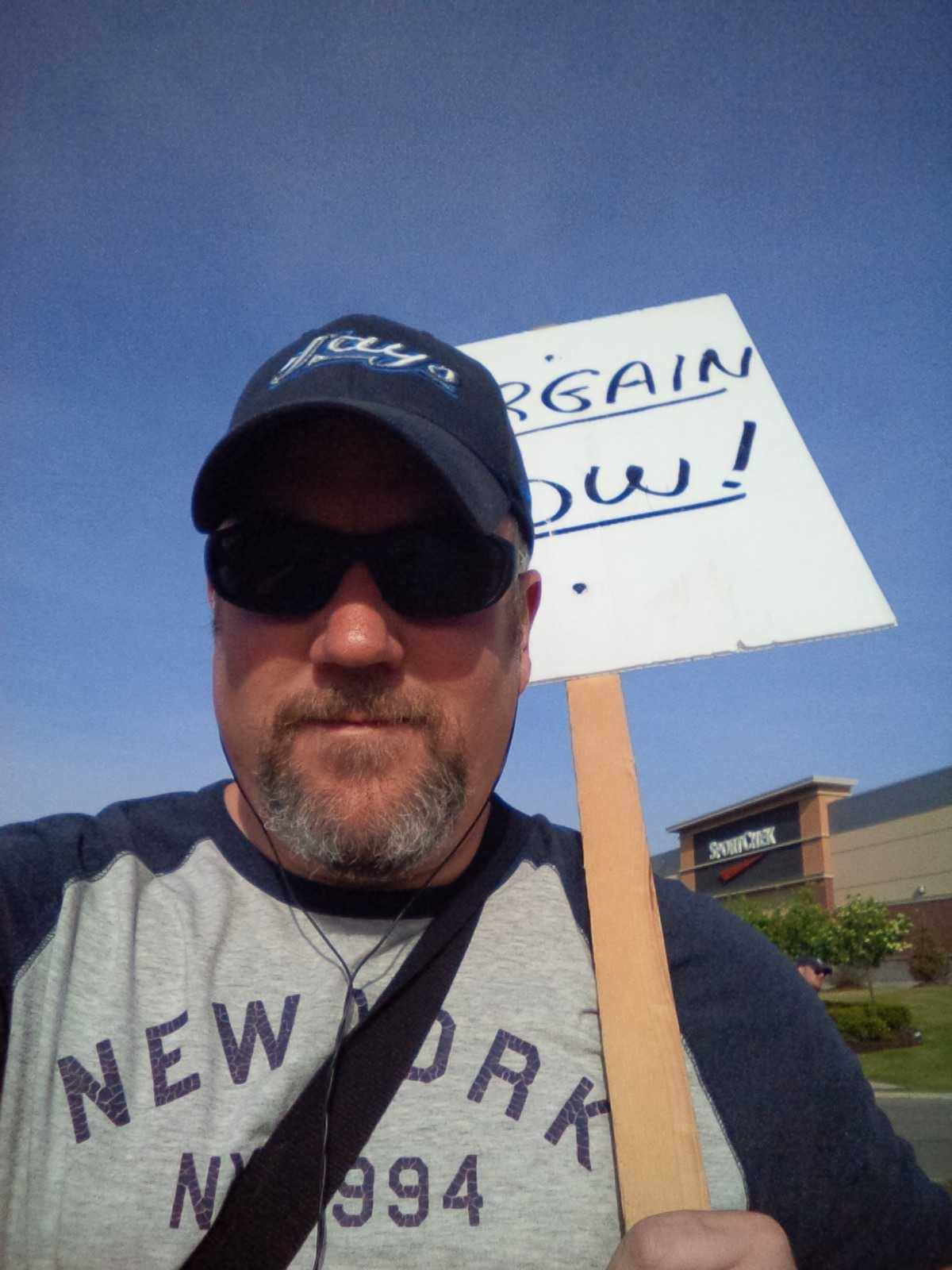

Finally, I made a connection between the readings and my experiences with the strike being deemed unlawful this past week. Much of the evidence that was used against the striking teachers was taken from oral recollections from witnesses who had interacted with picket liners (please see: http://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/2087236/durham-rainbow-peel-district-strikes-deemed.pdf ). That information combined with the written texts of the messages on the signs was used against the teachers to help determine the legality of the strike. I wonder if the evidence was purely based upon oral recollections of the interviewees whether or not I would still be on strike. How can one validate with authenticity any oral communication UNLESS it has been recorded? Ong refers to this on page 57.

I know that my response has been long and somewhat all over the place, but it reflects my own personal experiences and my life in the past several weeks. I think I have raised more questions than answers. In the end, I’m not entirely sure whether or not the disappearance of rote learning is having an adverse effect on students. I do know, however, that Google and other methods of looking up the answers are not going anywhere and that we as teachers either need to learn how to harness that energy and method or risk falling further behind our students.

Works Cited

News, CBC. “Ontario High School Teachers’ Strikes Illegal, Labour Board Rules.” CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, 27 May 2015. Web. 31 May 2015.

Ong, Walter J. “Some Psychodynamics of Orality.” Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. London: Routledge, 2002. 34+. Print.

“You know what you can recall” (Ong, 2003 pg. 32)

Your statements around rote memorization really resonated with me as it is a conversation I feel I have every year. I am not a teacher in the humanities so I can’t speak to the value of memorizing Canada’s provinces in a pedagogical sense. As someone who grew up in Canada and went through the process of learning all the provinces, and their capitals, and placing them on map, I feel that it was valuable. However that may be simply an opinion based out of nostalgia.

It is true that most anything can be looked up via google. With the increase in hand held devices within classrooms, the ability to look data up is literally in the palm of our student’s hands. For me the argument for students memorizing information falls under the umbrella of efficiency. I am an electronics teacher and in my classroom most of the time is spent with the students working independently. Until my students have memorized a fact like the resistor colour codes, the work flow bogs down. The kids can look up what resistor colour means what, and in fact there are websites that let you plug the colour codes in, however it is not efficient. Instead of increasing their tactile skills or tackling higher concepts in electronics their time is spent looking up facts. When Ong states “you know what you can recall” (ong, 2003 pg. 32) he is not saying you need to know the minutia of everything in electronics. However, if my students can’t quickly recall basic fundamentals I am unable as a teacher to move beyond the basics and efficiently teach students higher concepts.

Ong, Walter J.. (2003). Orality and Literacy. Routledge. Retrieved 26 may 2015, from http://www.myilibrary.com.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca?ID=1960

Hi Jody,

Your post resonated with me. I have fond memories of Grade 4 Math Flash Cards. I don’t know how effective it was for everyone, but it ‘gamified’ our learning, and we loved it. It is a distinct benefit to have memorized the multiplication table so I do not need to turn to a calculator each time, which might be rather embarrassing.

Equally so for French verb conjugation, then supported by songs, today supported by my Le Conjugueur app. And, of course, geography… I teach students who have little geographic knowledge. Surely, global citizens (if that is the aim) might like to have some degree of familiarity with world cities, or understand that Africa is not a country and China is not a continent. Canada may be a heterogeneous country, but if we are to be united and rally together when it counts, knowing where we are all from is a good start.

Of course, we can turn to Google now and then, but what if we are (gasp!) offline?

Thanks – and good luck at work!

Julia

Hi. Thanks for your response. I joke with the students about BG…before Google. What would we do? God forbid we use a book or an atlas or a globe to look things up. I still use my giant classroom map (even though it is so old that Nunavut isn’t on it!) to locate places. Google is a last resort!