The Technology Question

What is the effect of writing and other material literacy technologies on human thinking and human culture? (Haas, 1996)

In the first chapter of her book, Writing Technologies, Christina Haas poses the above question and summarizes a number of ways that different thinkers have attempted to answer it. One strength of her survey of the literature is how she breaks the different arguments down into philosophical, historical, and socio-psychological approaches.

Philosophical

Writing is considered by Plato to be ‘a psychological crutch’ that is inferior to speech. It takes away some of the truth that is intrinsic in the dialog that is the domain of human intellect. For Plato, writing is posing as wisdom as it encourages forgetfulness. It is mute in the face of questions and oblivious to the nature of its reader. For Derrida, however, writing does not exist in an imbalanced parent/child relationship with speech and is rather always present. Derrida argues that writing makes possible western philosophy as we know it. Haas uses these two philosophers, the contrast of their views, and the 2500 years that separates them, to illustrate the wide ranging implications that her “Technology Question” continues to have.

Historical

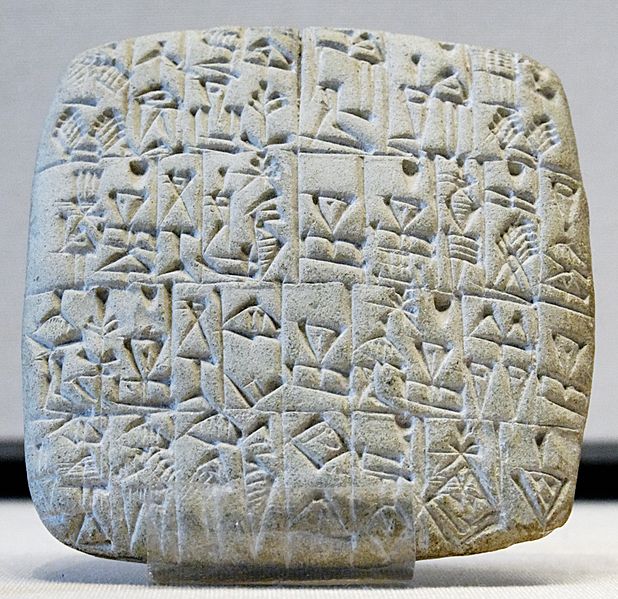

Through summaries of the work of Ong, Havelock, Goody, and Watt, we pick up on the common opinion that the jump from orality to literality was so profound that the modern, hyper-literate person can hope for only partial understanding of the mind of pre-literate people. Using the example of ancient Greece, we are shown how writing transformed the use of language from an aural construct to a material entity existing in space and time. The ‘seamless temporality’ of oral society becomes the literate world which makes and records distinctions between the past and the present. Logic, skepticism, and the very notion of history grow out of the ability to record the spoken word.

Socio-Psychological

Haas believes that the two previous approaches are useful but fall short in their attempts to interpret the affect that writing has on the individual, distinct from the culture to which they belong. Lev Vygotsky, in particular, was explicit in trying to describe how symbols restructure human thought processes. He regarded speech and writing as psychological tools that “can have a profound impact both on individual mental functioning and cultural change” (Haas, 1996, p. 15).

It is interesting to note that throughout Haas’s examination of other writers, the specific medium of the writing is unimportant. She uses the umbrella of ‘material literacy technologies’ to encompass any symbolic representation of speech. She argues, however, that writing’s technological aspect combined with its psychological dimension has the ability to profoundly transform human beings. So while she believes that even the simplest writing tool is technology, the advancement of that technology (from writing with a stick in the sand to our modern hypertextualized networks of text and images) will have effects on those transformations. However, the advancement of that technology is not deterministic or even straightforward. It is complex and must be contextualized in the culture in which it operates. Haas’s thesis is that every literate act incorporates technology and so an understanding of the relationship between writing and technology is important and necessary to a conception of human thinking and human culture.

Haas, Christina. (1996). Writing Technology: Studies on the materiality of literacy. New York: Routledge.

Hi Stephen,

This is a really interesting way of breaking down the relationship between the cultural and technical pieces of writing.

My own background is in philosophy and classics, so the philosophical angle really appeals to me. Ancient Greek society regarded people who did not social interact as an ‘idiotes,’ the root of the word ‘idiot’ in today’s language. The original meaning was meant for people who were excessively private and reclusive. Moreover, to be normal one had to be a political participant either through voting or speaking publicly. Writing against an idea or cause was not part of the culture. As such, speech was important for political action.

With how philosophy evolved since the Greeks, Derrida’s argument also makes sense. By the Middle Ages, philosophy became something of a scholarly pursuit, not a topic of conversation for most people. As a result, philosophy was divorced the political and became scholastic. Instead of philosophers gathering followers like Pythagoras or Plotinus, philosophers wrote books with the support of wealthy patrons. Philosophical dialogue came to exist through essays and books, not on stage or in public (we can leave that to the politicians). So the shift in technology makes sense if we think of public speech as political and reading as a private matter.

On the historical front, your analysis of Ong (1984) is right on. In just a few centuries it seems like the Greeks went from imitating speech to Aristotle’s logical syllogisms. The importance of writing on the mind is quite striking. That said, outside of scholarship, did the average Greek or Roman think in a preliterate way? Only a small portion were literate and we have preserved only the ideas of that select group like philosophers and politicians.

Ong, Walter. (1982.) Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. New York: Routledge.

Ober, Josiah. (1989). Mass and Elite in Democratic Athens. New Jersey: Princeton.