One of the things I look forward to in February is the Westminster Dog Show, a mega spectacle of dog owners, trainers, handlers and, of course, dogs. I like dogs, I have two of them. They are the very best dogs I know.

It is instructive to look beyond the crazy haired, hairless, majestic and cuter than ever faces at how after many rounds of judging one dog is named best in show. Investigating evaluation systems that are distinct from our own contexts of application provides a moment for reflection and perhaps learning.

Here’s what the WKC says about judging:

Each breed’s parent club creates a STANDARD, a written description of the ideal specimen of that breed. Generally relating form to function, i.e., the original function that the dog was bred to perform, most standards describe general appearance, movement, temperament, and specific physical traits such as height and weight, coat, colors, eye color and shape, ear shape and placement, feet, tail, and more. Some standards can be very specific, some can be rather general and leave much room for individual interpretation by judges. This results in the sport’s subjective basis: one judge, applying his or her interpretation of the standard, giving his or her opinion of the best dog on that particular day. Standards are written, maintained and owned by the parent clubs of each breed.

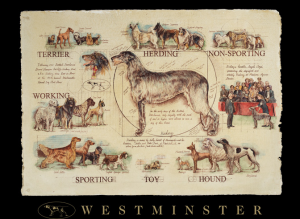

So come February there are successive rounds of dog judging leading to that final moment, naming the best dog. First, there are competitions within breeds to determine the best lab or poodle (standard, miniature and toy) and so on. To make the next round of judging manageable, breeds are then grouped… there are seven groups: sporting, non-sporting, hound, working, terriers, toy, and herding. This grouping is really a matter of convenience; the groups make sense but they are not mutually exclusive.  For example, terriers could be working dogs if hunting down vermin were considered work or terriers could be sporting dogs if hunting vermins were considered sport and clearly at least some of the terriers are small enough to be considered part of the toy group.

For example, terriers could be working dogs if hunting down vermin were considered work or terriers could be sporting dogs if hunting vermins were considered sport and clearly at least some of the terriers are small enough to be considered part of the toy group.

The grouping makes sense, but it isn’t a key feature of the evaluation process because in this round of judging dogs are not compared to one another, but to their own breed standard. For example, in the non-sporting group the Bichon Frise is not compared to the Dalmatian even though they are in the same group. The judge is making a judgement about each dog in relation to the breed standard and declaring that one (actually four dogs at this round) are the best examples of their breed. So if the Bichon wins in the group it means that the Bichon is an excellent Bichon and the Dalmatian is a less of an excellent Dalmatian.

The last round of judging to find the best dog looks at the best in each of the groups. Within the groups and at this culminating stage what continues to be notable is the variation, the dogs don’t appear to be ones that belong together. The judge again is comparing each dog to its breed standard, choosing the one that best meets the standards for its own breed.

The last round of judging to find the best dog looks at the best in each of the groups. Within the groups and at this culminating stage what continues to be notable is the variation, the dogs don’t appear to be ones that belong together. The judge again is comparing each dog to its breed standard, choosing the one that best meets the standards for its own breed.

So, dog judging is a criterial based evaluation system. This example reminds me of the protest thrown in the way of evaluation: “That’s comparing apples and oranges!” with the implication that doing so is unfair or even impossible. The WKC show illustrates that this is a false protest and that we can judge given an apple and an orange which is better, but that to do so requires a clear articulation of what makes an apple a good apple and what makes an orange a good orange. I tell my students that we make such evaluative judgements all the time, even when we are deciding whether to buy apples or oranges.

Grading each dog is a separate evaluation and then the grades of each dog are compared to one another–the dogs are not compared, the grades are. Now this grading and comparison isn’t made explicit and happens in the mind of the judge, presumably experienced evaluators. But, conceivably this stage of the evaluation could be made explicit. That it isn’t is a part of the evaluation procedure that assigns confidence in the evaluators’ expert knowledge–we don’t expect it to be explicit because we don’t need it to be in order to trust the judge/evaluator. It is a criterion based evaluation system that includes some considerable exercise of expert judgement (criterion based evaluation meets connoisseurship, perhaps).

Follow

Follow