IRBs were established to prevent the excesses of medical research that mistreated and exploited the innocent and often indigent. Institutional review boards have taken on a life of their own though, exercising far too much influence over what research questions can be asked and what research methodologies are acceptable. It is not surprising that researchers charge the IRB process with violating academic freedom. This has been especially the case for social sciences, but in this account a clinical researcher suggests the very same silliness and intrusiveness is applied in medical research. IRBs have taken an authoritarian, we know better than you do attitude that in the end likely does as much harm as good.

When evaluation makes a difference

The Foundation world is one where evaluation practice has flourished in recent years, indeed some exciting innovations in thinking about and doing evaluation have come from the energy and resources Foundations have put into evaluation of their efforts. While in the past Foundations have focused on the value of merely doing something socially responsible there was less focus on whether or not their largesse was making any difference. The power of evaluation can be seen by the more recent likelihood of Foundations revealing when their injections of funds and enthusiasm do NOT have the anticipated outcomes. Perhaps this is just the new accountability era effect, but evaluation is at the center of these fuller disclosures.

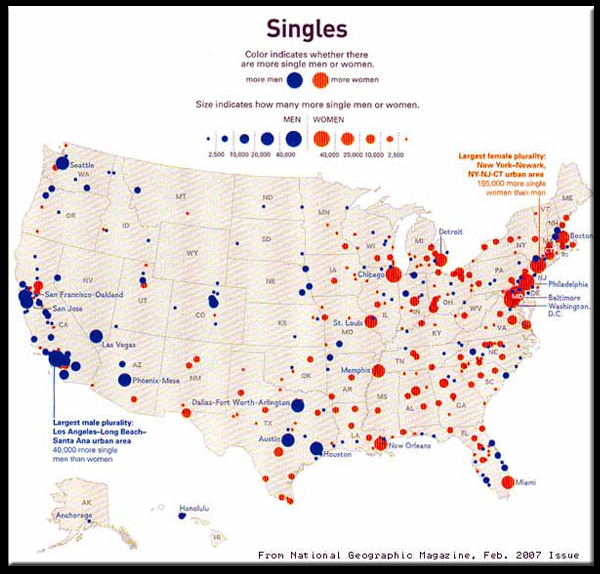

Maps as metaphor, image, and humour

Maps are a common image that serve many purposes. Sometimes a root metaphor (depicting anything as a journey or spatial relations), always with an aesthetic element, and usually meant to be informative (even if they are not always so). The blog Strangemaps is a collection of these various kinds of maps.

Visual displays of evidence

I have become a fan of Edward Tufte ~ he suggests that newspapers, like the NY Times and the Wall Street Journal, are light years ahead of social science in their ability to communicate large amounts of data in straightforward, comprehensible, and aesthetically pleasing ways. Here is an example of a simple kind of data (number of households mail is being delivered to) that over time illustrate the resurrection of New Orleans after Katrina. One could have used any uniform service to accomplish the same thing, but a mailing address exists whether any mail is actually delivered and does not differentiate people by class or race (like telephone or power service might).

There are any number of applications to evaluation for this particular data display, but it illustrates more generally ways to show the adoption or spread of something in geographic space.

Evaluation, more than efficacy

In this op ed piece, Francis Schrag points out a key feature of evaluation by comparing an evaluation of NCLB and the diabetes drug Avandia. A key element that must be included in any evaluation are side effects, the unanticipated outcomes. Even if the planned outcomes occur and in large measure they can be nullified by the presence of harmful unanticipated outcomes…’No Child Left Behind’ doesn’t provide full picture

Francis Schrag

Guest columnist — 6/13/2007

Newspaper readers may have noticed recent articles reporting test score performance of Wisconsin or Madison public school students as well as articles reporting controversy surrounding the diabetes drug Avandia. It’s illuminating to compare the two.

In the latter case, there is apparently strong evidence that Avandia is effective — it lowers the level of sugar in the blood. This fact, however, does not automatically lead to endorsement of the drug. Why not? Because as many now know, there are potential safety concerns, notably alleged increased risk of heart attack.

There is an important lesson here in the medical sphere that ought to carry over to the educational sphere: Efficacy is not all we care about.

Just as all drugs produce multiple effects, so do all education policies, such as the No Child Left Behind law passed in 2002. It is tempting to assess the impact of such a law simply by comparing test scores in math and reading (the two subjects where annual testing is authorized) before and after passage of the law. After all, test scores reflect student achievement, and that is presumably what we’re after.

Alas, this comparison, difficult enough to make for all sorts of reasons, is the equivalent of measuring blood-sugar levels before and after use of Avandia without taking into account any side effects.

Which side effects should be taken into account? It would be nice to evaluate many, but evaluation is costly and time-consuming, so let’s restrict ourselves to one that is significant: continuing motivation to learn in all subjects. Why this one? Because, just as the increased risk of heart attack may outweigh the beneficial effects of a diabetes drug, so might a reduction in continuing motivation outweigh a modest gain in achievement scores.

How could we assess continuing motivation? First, we need to compare the motivation of public school students subject to the law with matched private school students who are not. Second, we need to provide both groups of students with opportunities to manifest continuing interest in learning by giving them the option to participate in an activity that would manifest that interest, for example reading additional books over the summer or participating in an after-school science fair.

Evaluators will need plenty of imagination to come up with valid ways of tapping students’ motivation to learn. This may be difficult, but failing to consider important side effects of school learning is irresponsible. Without a conscientious effort to tap important side effects, we’ll have no basis for ruling out the possibility that a policy designed to raise test scores does so only by putting another valued outcome at risk.

We don’t want our educational policies to be the equivalent of Avandia, but so far we’re making no effort to find out if they are.

Francis Schrag is a professor emeritus in the Department of Educational Policy Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

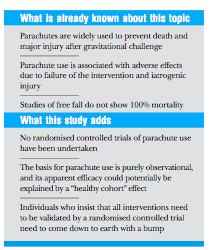

One more view of RCTs

Smith and Pell draw the following conclusions in their meta-analysis of studies of the impact of parachute use on death and trauma.

Read Parachute Use to Prevent Death and Major Trauma Related to Gravitational Challenge: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials in its entirety.

Evaluation, decision making, and other considerations

As is often the case, Dilbert gives us something to think about…

Most Significant Change Technique ~ an example

Most Significant Change (MSC) is a participatory monitoring technique based on stories of important or significant changes – they give a rich picture of the impact of an intervention. MSC can be better understood through a metaphor – of a newspaper, which picks out the most interesting or significant story from the wide range of events and background details that it could draw on. This technique was developed by Rick Davies and is described in a handbook on MSC.

Most Significant Change (MSC) is a participatory monitoring technique based on stories of important or significant changes – they give a rich picture of the impact of an intervention. MSC can be better understood through a metaphor – of a newspaper, which picks out the most interesting or significant story from the wide range of events and background details that it could draw on. This technique was developed by Rick Davies and is described in a handbook on MSC.

An illustration of how MSC is used is this report, Stories of Significance: Redefining Change, which is an evaluation of community based interventions for Indian women and HIV/AIDS.

Thinking about the cost of evaluation

Any evaluation must consider whether the indicators to be used are truly available and high quality, and whether the cost of data collection are warranted. The failure of the four large testing companies to satisfactorily meet state testing demands created by NCLB is an excellent example of the triumph of ideology over reasoned evaluation practice. The NCLB requirement that all students in grades 3 trhough 8 be tested has created a boom for the testing industry. However, the oligopoly of the four major testing companies cannot meet the demand nor do the job well. The incidence of errors is widespread and the inability of these companies to deliver the test scores accurately and in a timely manner is apparent across the US. The article US Testing Companies Buckling Under Weight of NCLB illustrates the pervasiveness of the problems. What the article does not mention is the deep and long standing connections between the Bush family and the testing industry, particularly CTB/McGraw Hill.

Point of View (POV)

The important “point of view” in evaluation is the context that provides the reference for making judgements about the quality of an evaluand.

There are a limited number of points of view that one might take in doing evaluation–some obvious ones are aesthetic, economic, political, religious. A POV is universal, i.e., for everyone and every culture there is each of these points of view. When one takes a POV, one necessarily takes certain criteria and indicators to be primary. For example, an economic point of view assumes things like markets, monetary value, and the like. Even though a POV is universal, within any POV there are potentially many orientations. Again using economics as an example, there are Marxist, free market, neo-liberal, fascist, and so on orientations.

Every evaluation is done from a particular POV and a particular orientation. Evaluators and all evaluand stakeholders will find evaluation more defensible and useful if there is clarity and agreement about what the POV and orientation for a particular evaluation is. Disagreement about assertions of value or dis-value are dependent on the context, from the point of view.

Follow

Follow