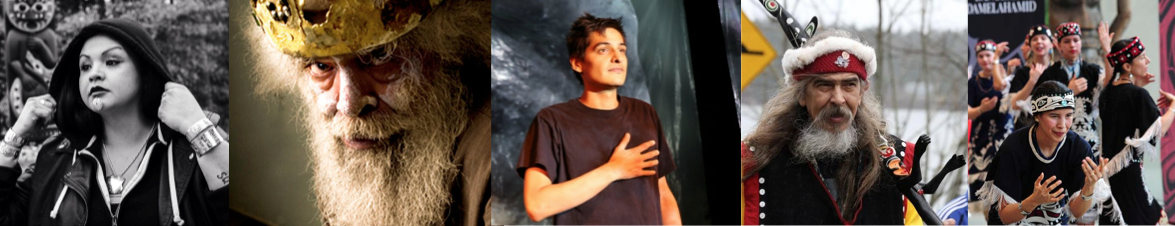

Git Hoan is a dance group out of Washington State that consists of dancer from the Tsimshian, Haida and Tlingit nations of Southeast Alaska. This group is lead by David Boxley who is a carver and culture bearer of the Tsimshian nation. The name Git Hoan means people of the Salmon.

The opening song consisted of dancers appearing from the back of the audience. These dancers made their way to the middle of the crowd within the performance space, dancing on the way. Here they formed a circle, dancing together off of the stage. After this initial song was over the dancers exited the stage and David Boxley entered to give the opening remarks. He acknowledged the territory the event was taking place on in both Sm’elgit and English. After this acknowledgement he went on to introduce the first piece that had already been performed and also talking about the second piece to be performed. The second piece also involved dancers forming circles, this time the dancers were both off and on the stage. Men and woman were playing drums and shakers on the stage as the dance took place.

The third piece was an honour song. The dance accompanying this song was done by 4 young men who represented 4 different clans. Three of the men were older while one young boy joined them on stage. The young boy kept up with the dance moves that were performed and synchronized by all four dancers. Occasionally the other dancers would smile down at the younger boy who wore a smile on his face throughout the performance. The facial expressions of the older men were serious for the most part. The dance was full of emotion, including passion, trust, and pride. I really enjoyed how they incorporated different ages into the performance of this piece. The importance of the dance was evident and the inclusion of the younger dancer showed the diversity of ages that hold the honour of different clans.

Although I have yet to experience different dance groups and diversity within the Indigenous dance community, I find aspects of these performances extremely unique and engaging. I have attended two Coastal First Nations Dance groups performances that were both spectacular in their own ways, and I am excited to witness more performances from a variety of areas. One aspect of Git Hoans performance that I found myself drawn to was the element of mystery they held in many of their pieces. The fourth piece they performed started with three dancers that were guided to the stage backwards. You couldn’t properly see their regalia or masks that they were wearing. After the guidance to the front of the stage they were covered with a blanket and turned around. This held the mystery and the anticipation of what was going to be revealed from under the blanket. Each blanket showed a picture of a different animal. As the music began, the dance started. People held the blankets in front of the dancers as they moved around the stage, not revealing the dancer behind the blanket yet. As the piece progressed, the blankets were finally removed from each of the three dancers. The animal represented on the blanket matched the mask that the dancer wore. At the end of the dance, the dancers stayed in their places and allowed fellow dance group members to guide them off the stage in a similar manner to the way they were guided onto the stage. The connection between the initial depiction on the blankets and the performers underneath was engaging. The mystery that was eventually revealed to show this connection was an aspect of the performance I truly enjoyed.

Another piece that displayed this level of mystery was the beaver song. This piece involved a huge centerpiece that was located in the middle of the stage. Dancers took the stage and danced around the centerpiece that consisted of a tapestry that looked like a beaver damn draped over a 4ft tall 3-walled box. The dancers danced around the beaver damn and as the piece progressed a giant beaver mask appeared from behind the ‘beaver damn’. This startled me, as the appearance of the beaver was paired with a sudden change in music. The music became loud and was intended to cause fear. The connection of fear with the appearance of the beaver never ceased throughout the performance. Different aspects of dance including motion, music and visual art can cause various emotions in the audience. Even though the space where the performance took place had a lot of people moving in and out between various pieces, each piece held the viewers full and undivided attention until the very end. I think this is why Indigenous dance doesn’t need to be performed in a formal setting, the informal settings hold viewers attention fully and completely.

The performance as a whole was beautiful. It contained a diverse age group of performers that engaged in many different dances as a whole. The regalia, masks and headpieces were absolutely breathtaking and helped the dancers to depict their story, message or meaning behind their dance to a greater extent.

Reviews:

http://ubyssey.ca/culture/review-coastal-first-nations-dance-at-moa-357/

Parts of this review show that the reviewer displayed clear knowledge of the dance group and also of first nations practices. I’m aware it is not first hand knowledge, but research was conducted in the area that depicts her interest in the area. An overall positive review, but some assumptions were made that should have been researched further. A higher knowledge on the subject from dance group members themselves should have been pursued before making statements such as “Such innovative masks indicate how cultural heritage of the Indigenous are not being merely passed on to younger generations, but how they are being actively transformed and integrated into their new perspectives their cultural traditions.” First hand knowledge should have been perused on the subject matter at hand.

No other reviews were found on this dance group at this festival; only various sites advertising the happening of the festival itself were present.

Some questions I had at the end of this performance were more reflective questions. What are aspects of Indigenous dance performance that you personally enjoy the most? If they vary between different types of dance, what is your favourite aspect of these various dances? When viewing performances what is the venue and environment that makes witnessing most enjoyable for you?

Presentation Slides: