The Ohio Public Library Information Network has been on a search for the perfect federated library, database, and web search engine since the late 1990’s. According to the article “Ohio Web Library Mashup” featured in the 2008 book Library Mashups: Exploring New Ways to Deliver Library Data, the librarians found what they were looking for in the pazpar2 software for Index Data. As the authors state:

“The pazpar2 software is a web-oriented Z39.50 client that can search a lot of targets in parallel and provides on-the-fly integration of the results. It works particularly well with AJAX (Asynchronous Javascript and XML) for building a dynamic page displaying search results. It provides record merging, relevance ranking, record sorting, and faceted results. This was the option that seemed to offer the functionality we needed, the features we wanted, and the critical ability to make rapid changes. We identified some features of the MasterKey hosted service which we felt could be improved, looked closely at the pazpar2 code, and came to an agreement with Index Data to install a slightly customized version of pazpar2 on one of our servers to be the engine for our federated search.”

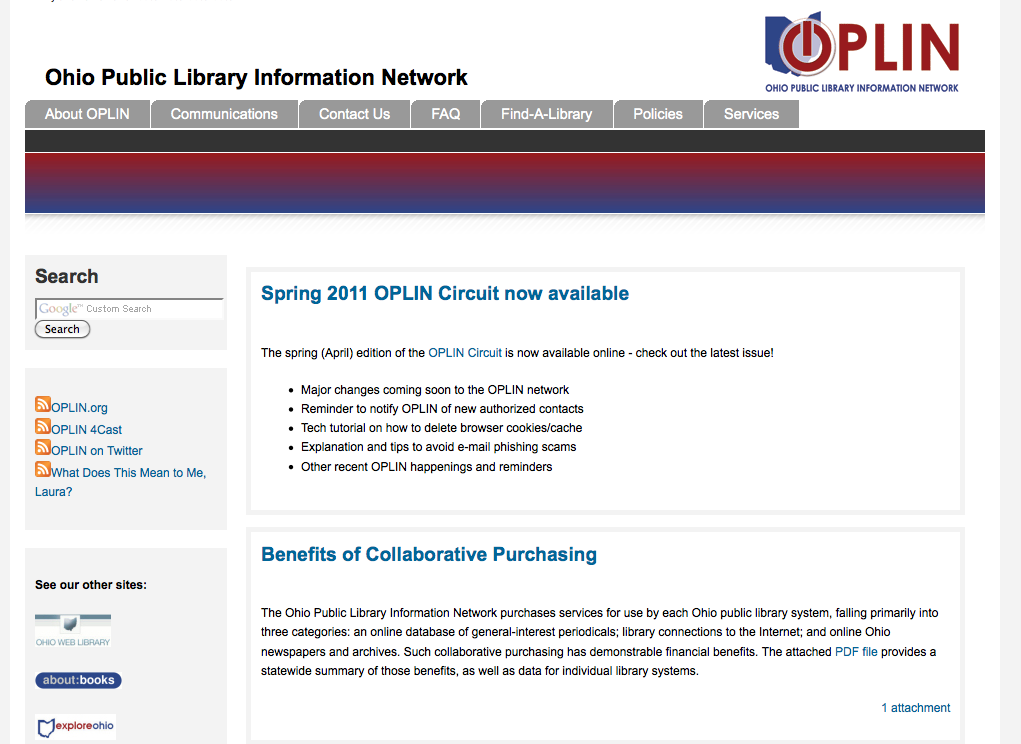

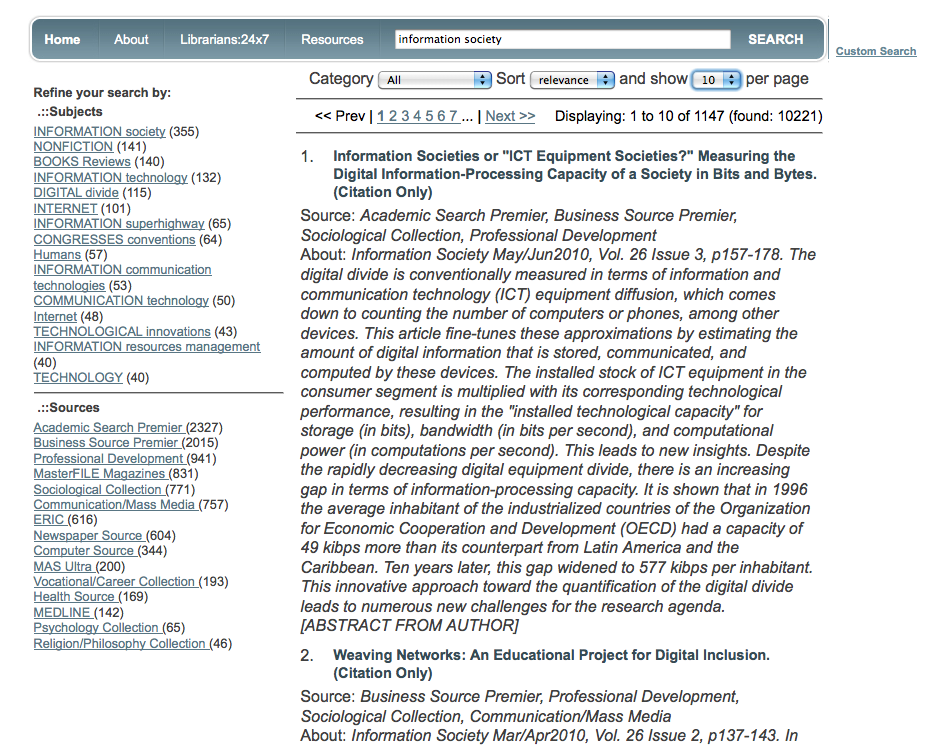

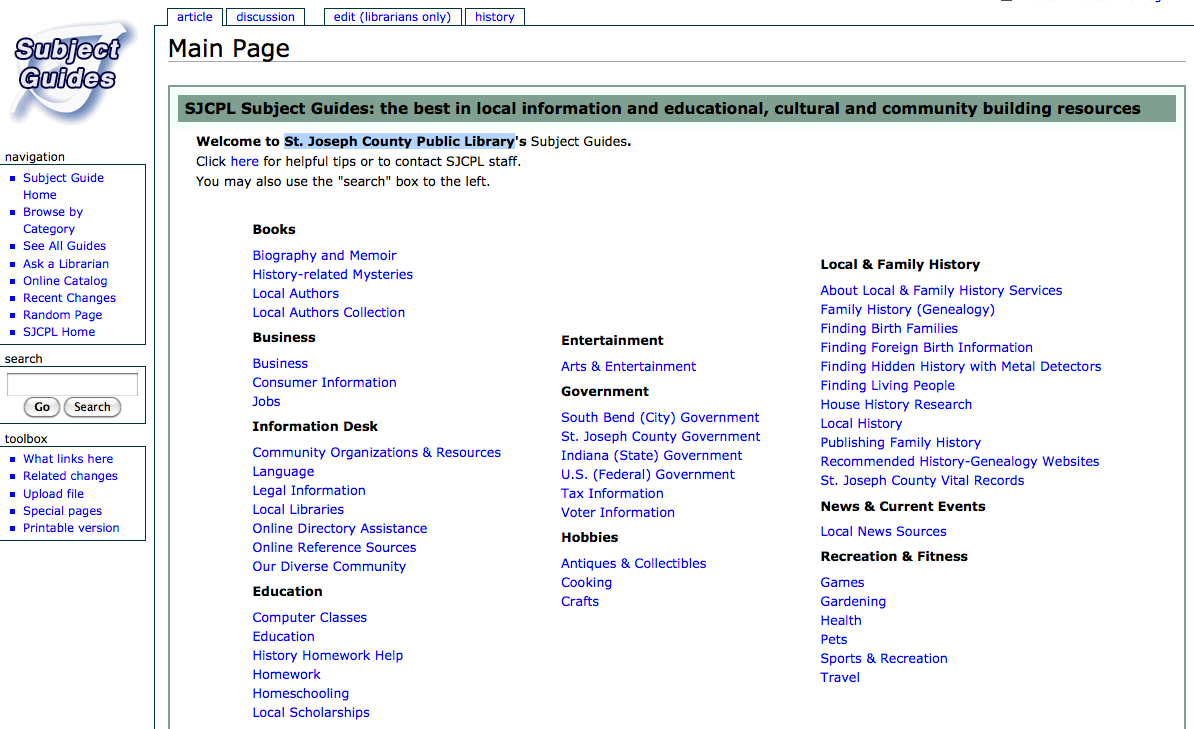

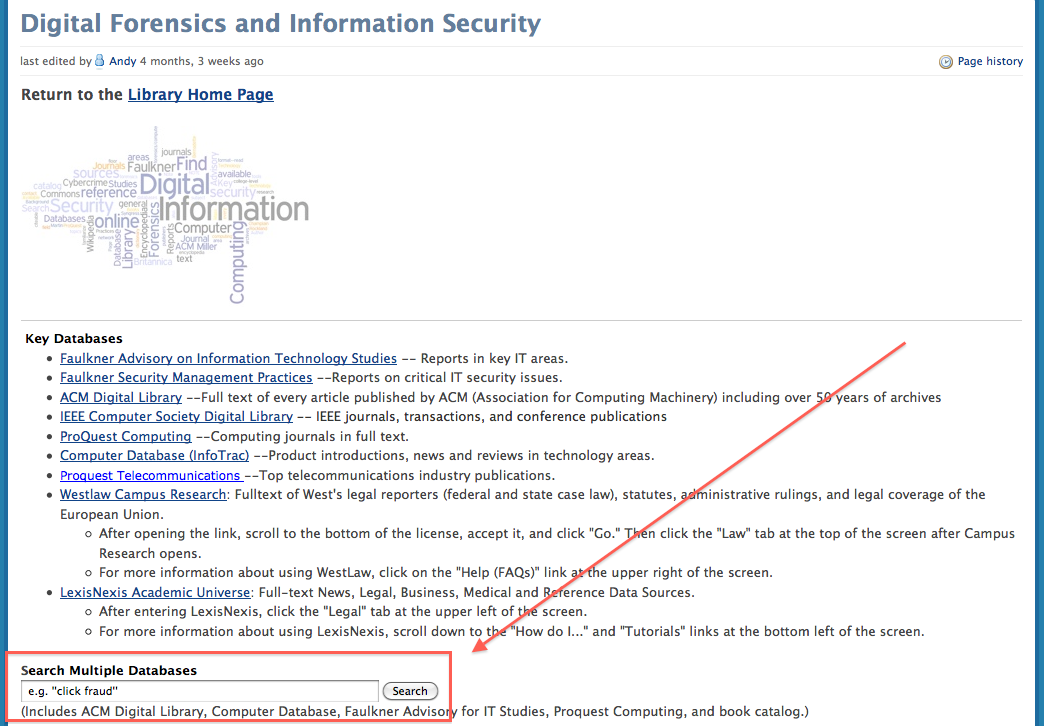

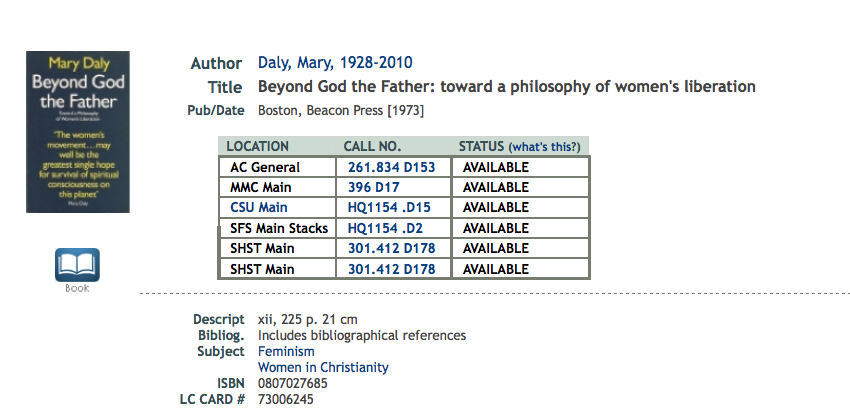

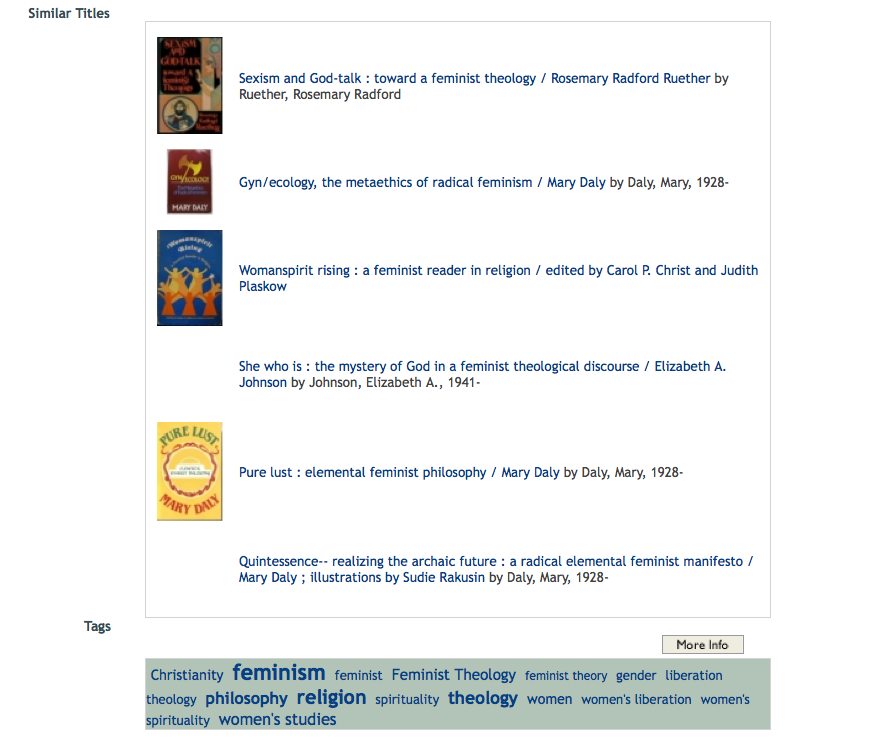

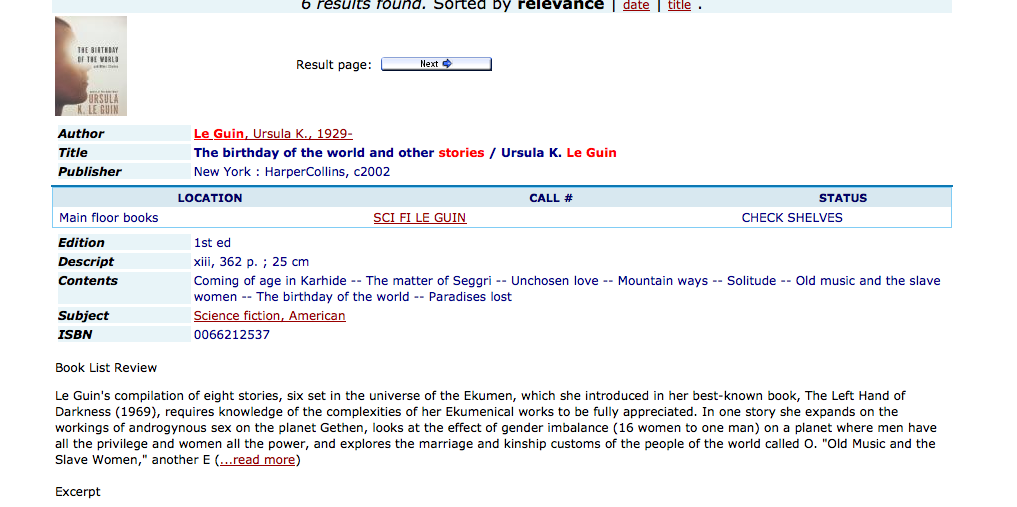

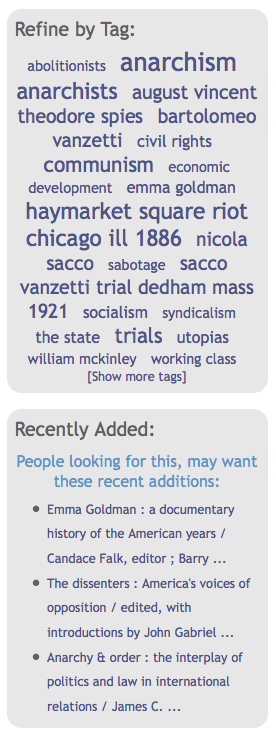

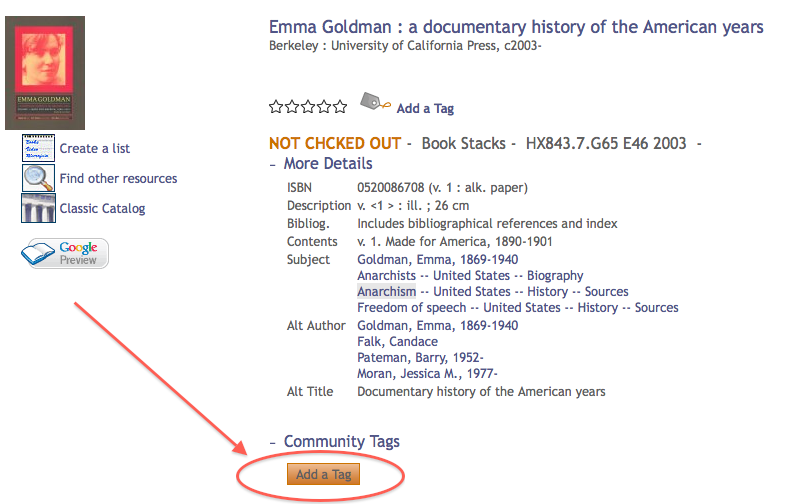

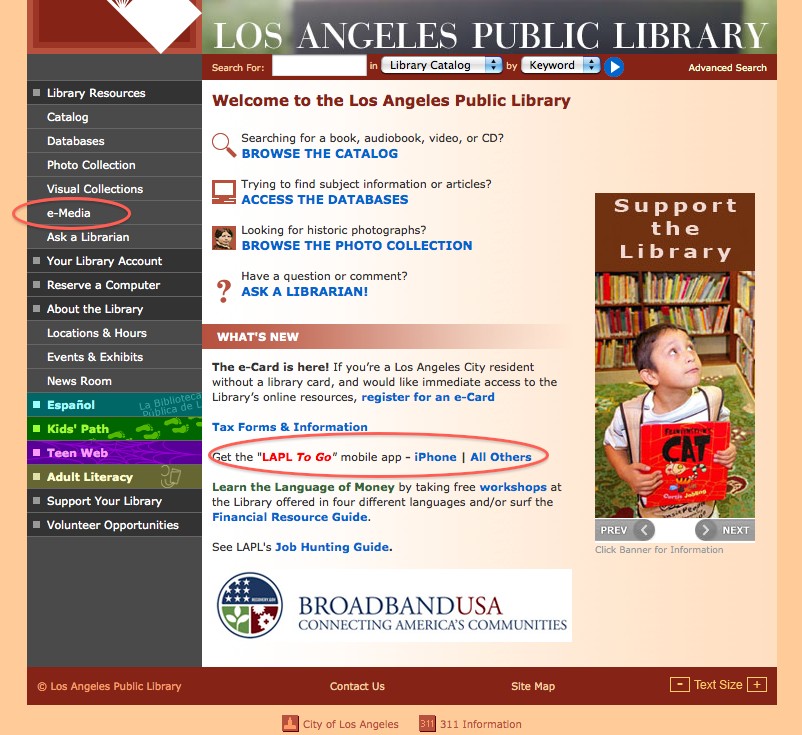

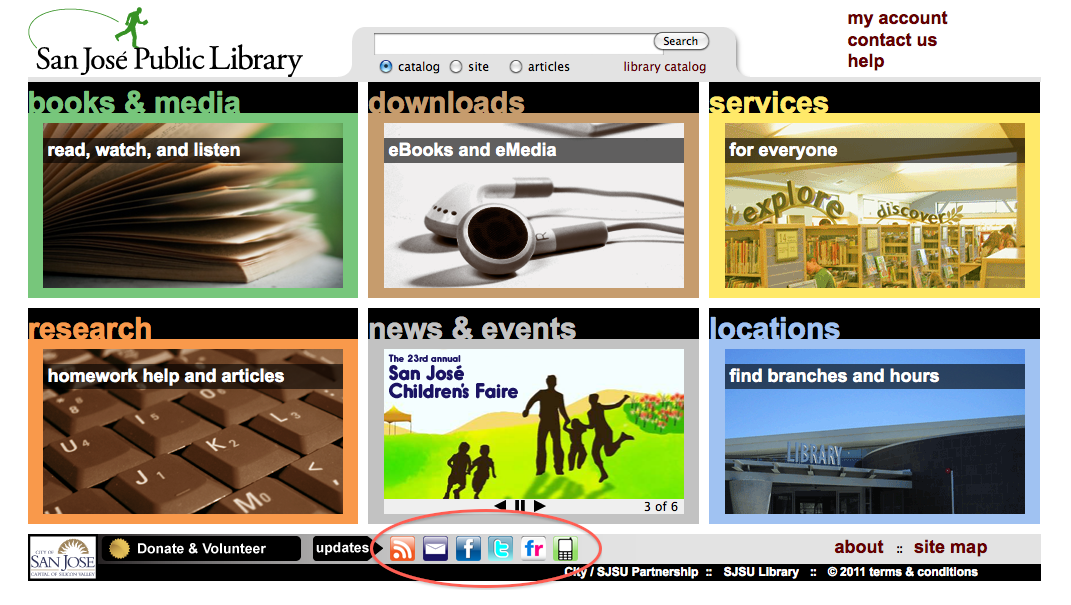

In an effort to provide a search service that was “more like Google” the librarians at OPLIN negotiated interoperability issues, evaluated vendors, prototyped models, and improved usability. The OPLIN’s universal search browser launched in 2008. Here are screen shots of the library network home page, the search bar, and a search example:

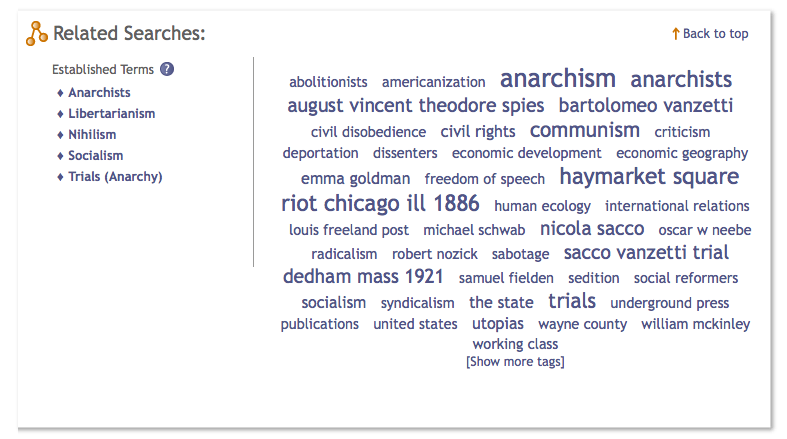

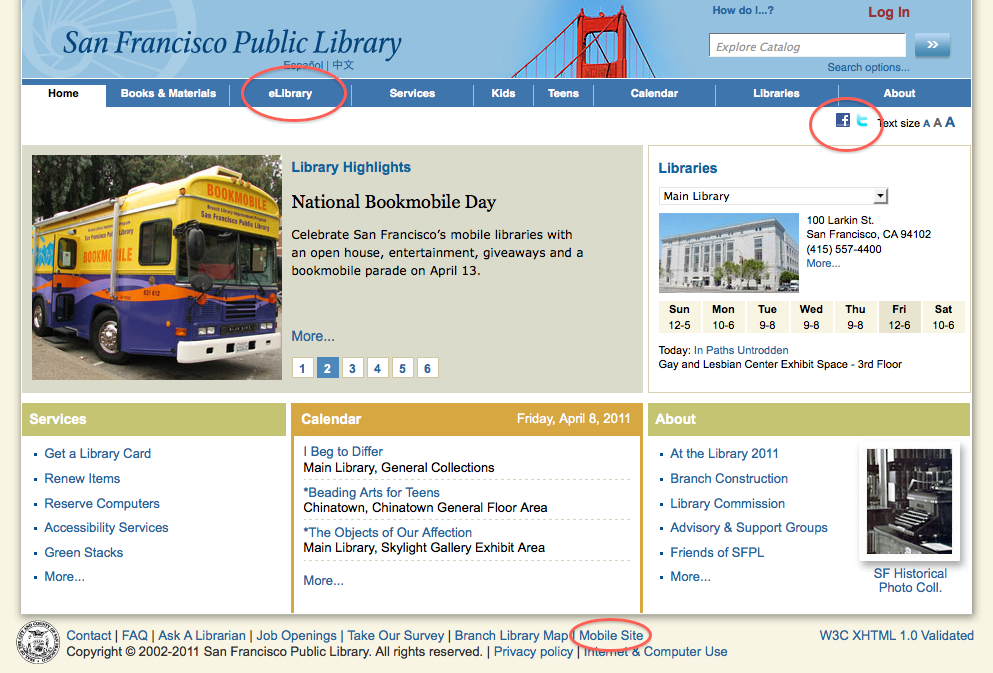

A couple of interesting things to note are the lists of “Subjects” and “Sources” to the left of the search results list. Another important thing to note is that individual public libraries within the state of Ohio each have their own website. What the OPLIN has developed is a “federated database search mashup” that retrieves authoritative open and closed web resources.

So, why am am I focusing on the OPLIN Web Library mashup? Well, for one, and I am being very honest here, many of the other library mash-up tools fall short of what I believe is helpful for users. Don’t get me wrong, features like mapping library locations or a bookmobile map, or other services that utilize free and open-source data in order to provide novel formats, services, interfaces, and functionalities can provide incredibly useful services to users. However, what I find exemplary and compelling about the specific example of the OPLIN was the ability for library staff to continue to go back and re-test, re-evaluate, and pay attention to what their users were looking for and what they need. Overall it is an excellent example of prototyping and beta testing new information technologies – the right way, and I think that information professionals everywhere can learn from this example.

Despite the great usability and usefulness of the “federated database search mashup” tool, among the few public library websites I checked (and they were only a few) the OPLIN did not seem to be featured as a research tool or resource. With the amount of work put into crafting this search tool, instructing other public libraries on its usability and strengths, as well as integrating the search bar into public library home pages, either by embedding or linking, would help to increase the use and awareness of this tool as an authoritative resource for database and online content.

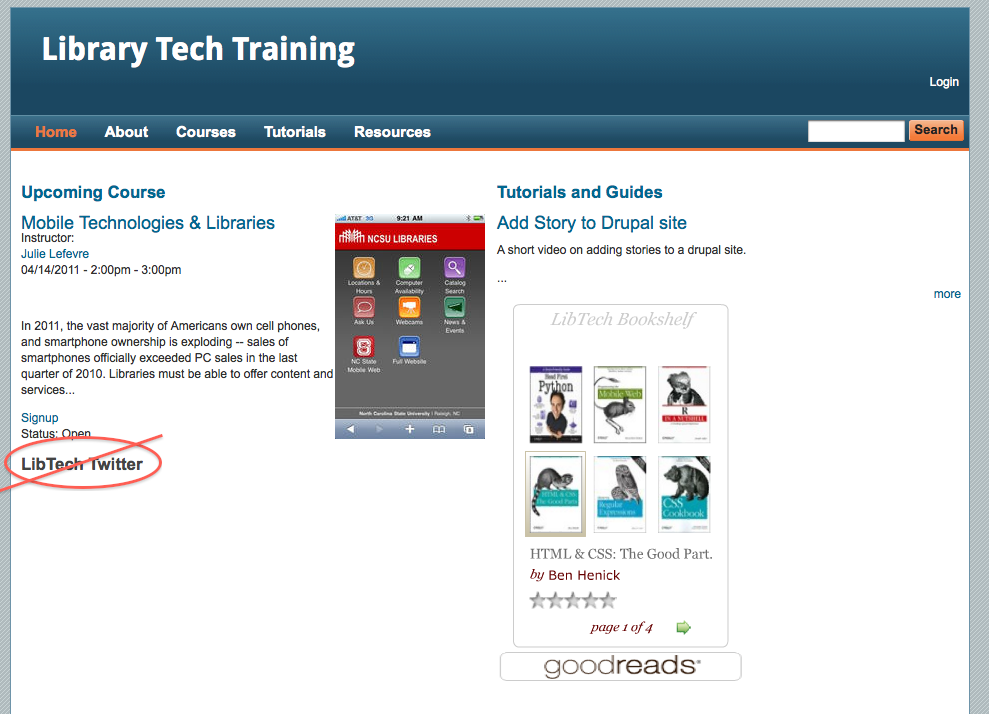

As much as I am in agreement with authors like Brian Lamb and Duanne Merrill regarding leveraging the power of new Web 2.0 technologies, I do think that the Library 2.0 movement could benefit by collaboration with open source and community informatics proponents. Besides, we all want the same things, but it’s helpful to be aware of some of the various ways and methods that information professionals are making it happen.