Always already.

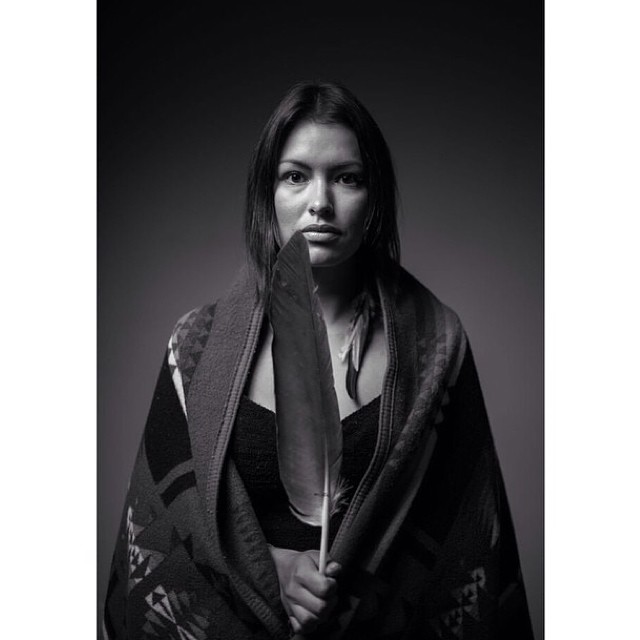

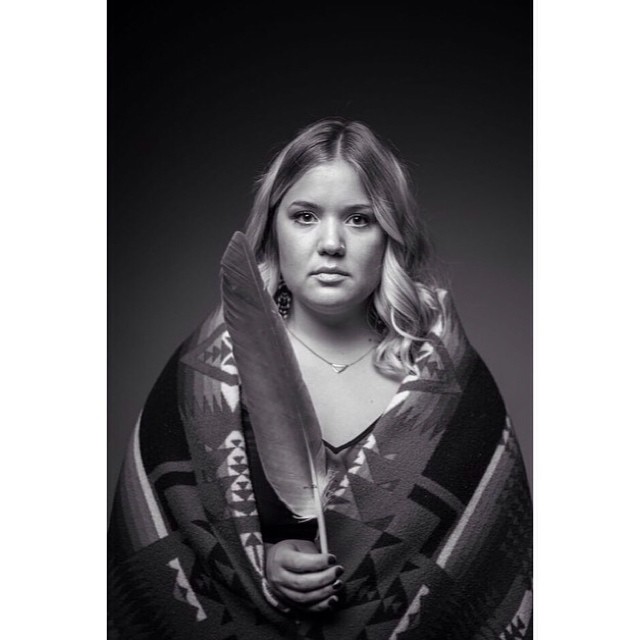

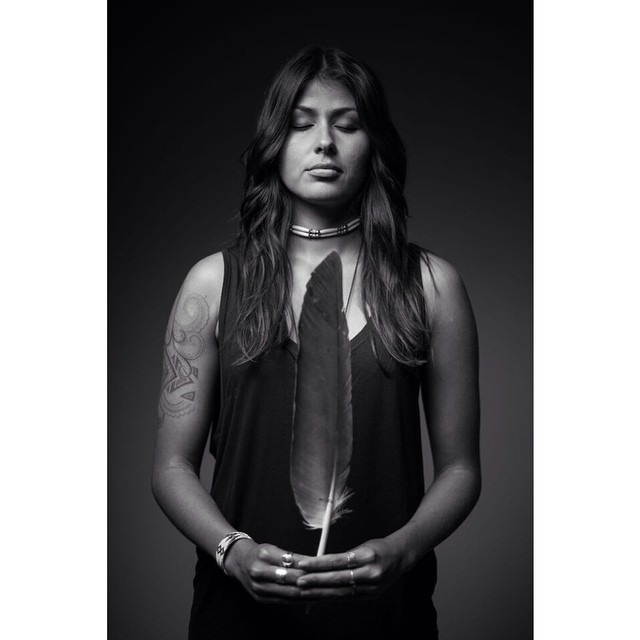

You like to label Indigenous peoples as a vanishing race,

try to erase us from the collective mind of the colonized State.

I imagine it’s easier for you, more convenient

if we have this inevitable fate hanging over us.

Easier, more convenient, to mourn for what was lost

rather than acknowledge your own role in destroying it.

Easier to hide behind your Imperialist Nostalgia.1

More convenient to continually frame Indigeneity as fragile, as

always already.

Always already vanishing.

Always already lost.

Always already dying.

Always already past.2

Always already.

Always: a strict checklist of prescribed expectations.

Always: leaving no room for unexpected behaviors, and definitely no alterations, but

always allowing for just a few anomalies– to reinforce imposed limitations.

Set definitions. Confine possibilities, so that

always already expectations become believed inevitabilities.3

Always already.

Expectations become so naturalized,

we forget to question where they came from in the first place.

Forget to question the ethnographic voice of Imperialist Anthropologists,

who whisper definitions in our ears as we sleep.

Forget that this ‘objective’ voice has mastered the art of telling dehumanized stories:

Observations void of emotions, then

we wonder where this notion of the ‘Stoic Indian’ came from, when

annotations about cultures leave no room for feelings or relationships.

Stuck in time. Snapshot definitions leave no room for malleability or transition.

And these constructed shadows of cultures still echo through history textbooks,

contextualizing the Native experience always already in the past tense:

As we become objects instead of subjects

in the sentences you create to justify your dominance.

In the same way women are objectified

so violence against us can become somehow justified in the eyes of the oppressor.

For us Inconvenient Indians,4

you use the same convenient reasoning:

Bodies inherently rapeable.

Land inherently invadable.

Resources inherently extractable.5

Cultures inherently erasable.

Whole peoples inherently incapable of being real.

But as much as you seek to steal,

our land,

our language,

our identities,

We are still here.

And that is your secret fear:

that actually, we will never disappear;

that we have always,

and will always,

be right here.

_________________________________________________________________________

1 Rosaldo, R. (1989). Imperialist Nostalgia. In Culture & Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis

(68-87). Boston: Beacon Press.

2 Lew, J. (2014). Lecture given in FNSP 300: Writing First Nations. Vancouver, BC.

3 Deloria, P. (2004). Introduction. In Anomaly and Expectation (3-14). Lawrence: University

Press of Kansas.

4 King, Thomas. (2012). The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North

America. Canada: Anchor Canada.

5 Smith, A. (2014, January 24). Decolonizing the Anti-Violence Movement. Lecture given during

UBC’s Sexual Assault Awareness Month. At Sty-Wet-Tan Hall, Vancouver, BC.

Molly Billows is from the Homalco Nation. She is in her final year studying Indigenous Peoples and Land Health in the Faculty of Land and Food Systems. She wrote this poem last semester during FNSP 300 Writing First Nations, taught by Janey Lew.

Follow

Follow