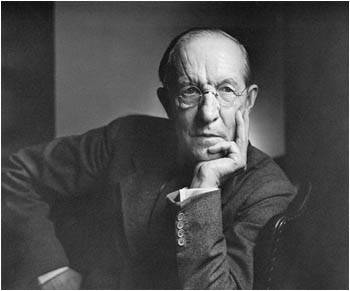

Duncan Campbell Scott.

Admittedly, this is a name that is foreign to me. Born in 1862, he was known as a writer. More importantly, he was the deputy superintendent of the federal Department of Indian Affairs (McDougall, “Duncan Campbell Scott”). His role as a civil servant has scarring impacts on Canadian history, as he was in favour of the government’s policy of assimilation of the First Nations (McDougall, “Duncan Campbell Scott”).

Speaking about residential school in 1920:

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem … That has been the objective of Indian education and advancement since the earliest times … Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic …” (Troniak, “Addressing the Legacy of Residential Schools”).

Interestingly enough, Scott’s work highlights his own duality. In The Bush Garden, Frye uses this excerpt of Scott’s own literary work to illustrate the point:

“He writes of a starving squaw baiting a fish-hook with her own flesh, and he writes of the music of Dubussy and the poetry of Henry Vaughan. In English literature we have to go back to Anglo-Saxon times to encounter so incongruous a collision of cultures” (221).

The duality of the sophisticated versus the primitive narrative in Scott’s stance is quite puzzling. However, his true position may have been more one-sided than what appeared to be. Although he seems to praise the First Nations, the romantic of the “vanishing Indians” does more harm than good. According to Dr. Paterson, his doubleness was never brought to light (“Lesson 3.1”). In an article from The Tyee, author Mark Abley notes how “its abstract rhetoric bears no relationship to the lived experience of human beings” (“Duncan Campbell Scott: The Poet Who Oversaw Residential Schools”).

In spite of Scott’s multiple attacks on the Indigenous people, his role appears to be moot in influencing Frye’s observation. One explanation which may partially account for this is his stance that a good portion of Canadian culture phenomena aren’t purely Canadian. Instead, they are “typical of their wider North American and Western contexts” (Frye 216). Consequently, Scott bears of little significance in his capacity to affect Frye. Since Frye states that there’s no pure Canadian identity, it might also imply how First Nations don’t have one united identity. This breaks free from the image of the “real Indians” (King 141) that are perpetuated in Hollywood and other media. With this being the case, Frye isn’t affected by Scott.

Moreover, Frye theorizes how aspects of literature have evolved to be more structured in its form. He calls literature “conscious mythology” (234): as society flourishes, its mythical stories become rules of storytelling. In an established literary tradition, Frye argues that writers are faced with a set of ideologies and expectations to follow. Since the mythical was the “prehistoric”, writers had to voluntarily attach themselves to the norm. It is as if writers were squeezing themselves into a tight pair of jeans, as they did not shape their own ideas. Instead, it’s a place “where a verbal structure is taking its own shape” (235). If Frye sees Scott as having to fit his writings with his role as a civil servant/Canadian government, then he may view it as less credible and therefore less influential. This can be supported by “the Canadian who wanted to write started with a feeling of detachment from his literary tradition” (Frye 235).

I also happen to believe that the irrelevancy of Scott’s role in forming Frye’s observation is a more inclusive manner of approaching the subject manner. It may be a technique in which Frye uses specifics examples to give readers some context, but uses a more broad approach to draw his own opinions. I’d also like to believe that it allows the reader to draw upon personal experiences, allowing for better understanding. Because it’s not just the Indigenous people’s cultures who were bottlenecked. They are also the Chinese, Japanese, Indians, etc, who have been historically affected by the melting pot concept. After the last several weeks of readings, writing, and dialogue, the approach Frye takes a slight break from the reoccurring theme of the dichotomy. Frankly speaking, I am liking this break from the “us versus them”.

Works Cited

Albey, Mark. “Duncan Campbell Scott: The Poet Who Oversaw Residential Schools.” The Tyee- Duncan Campbell Scott. TheTyee.ca. 8 Jan. 2014. Web. 2 July 2014.

Frye, Northrop. The Bush Garden: Essays on the Canadian Imagination. Concord: House of Anansi Press, 1995. Print.

Karsh, Yousuf. Duncan Campbell Scott. Photograph. 16 Sept. 1933. Library and Archives Canada/C-2187. Web. 3 July 2014.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print.

McDougall, R.L. “Duncan Campbell Scott.” Duncan Campbell Scott- The Canadian Encyclopedia. The Canadian Encyclopedia. 8 Aug. 2008. Web. 2 July 2014.

Paterson, Erika. “Lesson 3:1.” ENGL 470A Canadian Studies Canadian Literary Genre 98A May 2014. UBC Blogs. n.d. Web. 2 July 2014.

Troniak, Shauna. “Addressing the Legacy of Residential Schools.” Current Publications: Aboriginal Affairs: Addressing the Legacy of Residential Schools (2011-76-E). Parliament of Canada. 1 Sept. 2011. Web. 2 July 2014.

sharper(BESimpson)

July 8, 2014 — 5:02 pm

Hi Jenny-Great post : ) I was intrigued by your analysis of Frye and Scott, particularly in terms of your observation that Frye might have undervalued or dismissed Scott’s work based on the fact his writing might have been restricted by the influence of the Canadian government’s policy on “Indians” and culture assimilation. If Frye wasn’t influenced directly by Scott, could one still argue perhaps that the very idea of a “melting pot” culture comes from the policies Scott advocated? And in turn, could if then be argued that Frye’s opinion of a “detached” and “unfinished” Canadian literary tradition demonstrates, as least in Frye’s opinion, that the idea of a “multi-cultural melting pot” where all the cultures “assimilate” is a failure, or at the very least unachievable? Also, when the Europeans worked so hard to erase any “different” groups existing within their “stolen land”, where does that leave their own identity?

I love forward to working with you on our group project : )

Cheers, Breanna

jennyho

July 8, 2014 — 10:30 pm

Hi Breanna! I definitely think that the policies that Scott and the government advocated for definitely play into the idea of the melting pot culture. I don’t think the melting pot concept would go well in Canada, or anywhere else for that matter. What would all the cultures agree to assimilate to? I highly doubt it will be anything but Western/European… and then for whoever belonged to the Western/European cultures will be “above” the others, if that makes sense. Actually, this reminds me of George Orwell’s Animal Farm and the quote: “all animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others”.

As for your last question- hhmm, good one. It’s something I need to think about…

And I look forward to working with you too!

erikapaterson

July 28, 2014 — 9:43 pm

Hi Jenny – I am not sure where you got the idea that Frye dismissed Scott as a poet – not at all. Indeed, Scott is one of the canonized and so called ‘Confederation Poets’ – and much admired and discussed by Frye? As I say in this lesson:

“There is one last part of Frye’s conclusions that needs attention, and that is his description of the “second phase of Canadian social development” and his designation of Duncan Campbell Scott as “one of the ancestral voices of the Canadian imagination” (247). The second phase of development arises when “the conflict of man and nature” expands and becomes a “triangular conflict” that includes the individual, nature and society. When the poet allies himself “with nature against society” a new theme emerges and Frye says that “[i]t is the appearance of this theme in D.C Scott which makes him one of the ancestral voices of the Canadian imagination” (247).”

I am wondering if perhaps the question was not clear enough for you? It is Frye’s lack of concern, morally let’s say — for Scott’s role as an Indian Agent, I am questioning.

jennyho

July 29, 2014 — 10:34 am

Hi Dr. Paterson, thanks for raising your points. Yes, it’s a bit disconcerting that Frye didn’t appear to show concern for Scott’s role as an Indian Agent. Correct me if I’m wrong, as I don’t have any of the readings currently on me, but there doesn’t appear to any mention of Scott in a negative light?