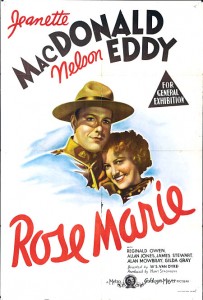

For this lesson, I was assigned to contextualize pages 130-142 in Green Grass Running Water. This section begins with Jeanette and colleagues arriving at the Dead Dog Café. Elected as spokesperson for the table, Jeanette introduces her friends Nelson, Rosemarie De Flor, and Bruce. Rosemarie is an allusion to the 1936 American movie Rose-Marie (“Rose-Marie (1936)”). Originally, I had thought that Rosemarie may have been a reference to the herb rosemary. In the film, the female lead is Marie de Flor, but later calls herself as Rose (“Rose Marie (1936 film)”). Jeanette MacDonald is the actress that plays Rose-Marie. Her love interest is Canadian Mountie Sergent Bruce, played by actor Nelson Eddy. MacDonald and Eddy were in an off-screen romantic relationship but never married each other. In the book, Bruce was a sergeant with the RCMP for 25 years, just as Bruce in the  movie played a Mountie. Rosemarie in the book mentions that she was in opera, just like Rose-Marie. On page 133, Nelson sings “when I’m calling you, oo-oo-oo, oo-oo-oo!”. This is a reference to the signature song of the movie, “Indian Love Call” (Flick 152). The song is based on a supposed Native American legend of how men would call down into the valley to women they wished to marry (““Rose-Marie”, or “Indian Love Song” (Part One)”). Just like the deeply rooted misrepresentations in the movie, Bruce’s continual questioning of Latisha over the “dog meat” illustrates Western cultural authority and the false beliefs people have of the Indigenous people.

movie played a Mountie. Rosemarie in the book mentions that she was in opera, just like Rose-Marie. On page 133, Nelson sings “when I’m calling you, oo-oo-oo, oo-oo-oo!”. This is a reference to the signature song of the movie, “Indian Love Call” (Flick 152). The song is based on a supposed Native American legend of how men would call down into the valley to women they wished to marry (““Rose-Marie”, or “Indian Love Song” (Part One)”). Just like the deeply rooted misrepresentations in the movie, Bruce’s continual questioning of Latisha over the “dog meat” illustrates Western cultural authority and the false beliefs people have of the Indigenous people.

The latter half of this section details George and Latisha’s relationship. George Morningstar is a reference to George Custer, who was the youngest general in the Union Army in the United States (Flick 151). George’s name alludes to Custer as he was nicknamed “Son of the Morning Star” or “Child of the Stars” (Flick 33). Both Georges were extremely “flamboyant in life” (“George Armstrong Custer”), sharing many of the same physical attributes and personalities. Near the end, George gifts Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet to Latisha. According to Flick, the book is a collection of “soft hokum, phoney philosophy- just the kind of stuff for George” (152). To bridge the first and second sections together, Latisha and Jeanette makes a reference to the toilet. On the next page, Eli mentions to Sifton how the dam reminds him of a toilet.

The focus of the second section is on Eli, his youth, and the Sun Dance. One reference that is made is the “big project in Quebec” (King 136). Here, King refers to the James Bay Project, which was a hydroelectric-power development that was announced in 1971 but contested by the Cree (Flick 152). The character Cliff/Sifton is an allusion to Clifford Sifton, a Canadian politician that was  known for his aggressive promotion of immigration to the western interior of Canada (“Sir Clifford Sifton”). Similarly, Lionel’s mother, Camelot, is a reference to the fictional court associated with King Arthur (Flick 152). The fictional quality of Camelot may represent Bill’s false beliefs of the Sun Dance, or what he calls the powwow (King 139).

known for his aggressive promotion of immigration to the western interior of Canada (“Sir Clifford Sifton”). Similarly, Lionel’s mother, Camelot, is a reference to the fictional court associated with King Arthur (Flick 152). The fictional quality of Camelot may represent Bill’s false beliefs of the Sun Dance, or what he calls the powwow (King 139).

At the end of this segment, Sifton recalls a story he read about a guy who said “I would prefer not to” (King 142). This is in reference to “Bartleby the Scrivener” by Herman Melville. In the short, a ordinarily compliant and hard worker defies his boss’ request to examine a small document (“Bartleby the Scrivener”). This parallels Eli’s defiance to the dam project.

I find it rather intriguing that King makes a number of allusions to well known Western figures, literary works, and popular culture. What really caught my attention was the mention of the Sun Dance. On page 138, King lists the food that was piled around the flagpole of the Sun Dance: bread, macaroni, canned soup, sardines, and coffee. Although I know next to nothing about the Sun Dance, my intuition tells me that the choice of foods are significant in some way. I think it is highly unusual to celebrate such an important ceremony with foods from the culture that oppress the Indigenous. However, King may have been intentionally selective of the allusions he makes in the book. He might believe if the reader has “read something that they too have done, they feel like someone watched them do it” (8). He might be having readers try to understand how we pick and choose what types of stories we listen to, just as he does in writing his own. As King said in an interview, “satire is sharp. It is supposed to hurt; it is never supposed to make you feel comfortable” (8).

Works Cited

“Bartleby the Scrivener.” SparkNotes: Melville Stories: “Bartleby the Scrivener”. SparkNotes, n.d. Web. 16 July 2014.

Doré, Gustave. Idylls of the King. Illustration. 1868. Wikipedia. Web. 17 July 2014.

eldatari. ““Rose-Marie”, or “Indian Love Song” (Part One).” Words and Names. WordPress, 27 Oct. 2010. Web. 17 July 2014.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water”. canlit.ca. Canadian Literature, 9 Aug. 2012. Web. 2 July 2014.

“George Armstrong Custer.” PBS. The Film West Project and WETA, 2001. Web. 15 July 2014.

Hall, David. “Sir Clifford Sifton.” Sir Clifford Sifton- The Canadian Encyclopedia. The Canadian Encyclopedia, 2008. Web. 16 July 2014.

King, Thomas. Green Grass Running Water. Toronto: Harper Collins, 1993. Print

MacDonald, Jeanette & Nelson, Eddy. “Indian Love Call.” Video. Youtube.com. YouTube, 1936. Online. 15 July 2014.

“Rose-Marie (1936).” IMDb. Amazon, n.d. Web. 15 July 2014.

Rose-Marie. Image. 1936. Wikipedia. Web. 17 July 2014.

sharper(BESimpson)

July 22, 2014 — 4:55 pm

Hi Jenny-I liked your post : ) I hadn’t noticed many of those allusions and connections before, and I found the allusion to George Custer particularly interesting-it puts the novel’s George into a whole new light. I had two questions for you-did you find that any of the popular Western culture references made the story more relatable to you, or more jarring? For myself, I found the references often obscure and always disconcerting, leaving me unsure as to King’s intended message. Also, King’s quote about satire: “satire is sharp. It is supposed to hurt; it is never supposed to make you feel comfortable”-I found the satire in the novel made me confused and rather uncomfortable in many places, sometimes for unidentifiable reasons. I found this feeling of discomfort was amplified when I understood the references being made. What about you-did you find that understanding the subtext and allusions changed your reading of King’s use of satire in the novel?

jennyho

July 22, 2014 — 7:42 pm

Hey Breanna, my knowledge in the area of Western culture is pretty limited. Everything that I wrote in this post is new information to me. Even though I learned more about the references being made in this section, I didn’t find that they were more relatable to me at all. If anything, most of the allusions in this book probably made me feel more distant.

To answer your second question: the more I read, the less I knew. When reading this subsection that I had to analyze… I guess I felt like I had some understanding of what King is speaking of, but I would feel confused and lost after. Why King chooses to do what he does, I’m not entirely sure. As the saying goes, the more you learn, the less you know.

Did you find yourself frustrated while reading GGRW because of how you felt? Without a doubt, all the references and allusions King makes are very clever and intelligent. If one of his intended purposes is to have people understand the issues surrounding Indigenous peoples, doesn’t all the referencing hinder people from learning about them? I wonder if the book has become complex to the point where it becomes inaccessible by the general population. Or was the intended audience meant for a specific readership?

Caitlyn Harrison

July 23, 2014 — 12:00 am

Hi Jenny! I find it interesting that you mention how “King lists the food that was piled around the flagpole of the Sun Dance: bread, macaroni, canned soup, sardines, and coffee.” I honestly didn’t even notice this when I was reading the novel and I think you’re right, it seems like it is significant in some way. I’m torn about how to interpret this detail. A part of me wonders if it is in reference to how damming the rivers has contributed to changing the traditional diet of various First Nation’s cultures and another part of me is reminded of ““I’m not the Indian You had in Mind”– in other words, challenging our expectations about what a First Nations person can be/eat… What are your thoughts on this? I could be way off!!

jennyho

July 23, 2014 — 12:17 am

Hey Caitlyn, you brought up a really valid point I’d fail to consider (I’m Not the Indian You had in Mind). I also didn’t consider about the loss of food source due to the damming of the rivrer,

To answer your question: I was so wrapped up in how important the Sun Dance is that I forgot to consider the poem/video. I can recall that there’s a part where someone mentions that Lionel selling TVs is a departure form the stereotypical jobs, and there seemed to be a reference to the poem. But in this excerpt, there was nothing that seemed to refer to “I’m Not the Indian You had in Mind. I’m also wondering if there’s anything significantly import relating to the chosen foods…what do you think?

erikapaterson

July 29, 2014 — 5:49 am

Hi Jenny – ummmmm, I am pretty sure King is making a joke when he lists the food at the Sundance:

“King lists the food that was piled around the flagpole of the Sun Dance: bread, macaroni, canned soup, sardines, and coffee. Although I know next to nothing about the Sun Dance, my intuition tells me that the choice of foods are significant in some way. I think it is highly unusual to celebrate such an important ceremony with foods from the culture that oppress the Indigenous.”

It would be interesting for you to learn more about the Sundance ceremony – if I see another blog with some research on this, I will alert you.

jennyho

July 29, 2014 — 10:14 am

Hi Dr. Paterson, if what you’re meaning is that the types of foods he choses to list is meant to be a joke, then yes, I agree with you. Not sure if my point was made clear, but what I mean to say is the type of foods (and other things in general) that are chosen for such a special ceremony are usually very important. There is definitely some sort of joking around in the list he makes. And yes, it would be interesting to gain some insight on the Sun Dance!