It’s been roughly three months now since the US and her allies began waging war against the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham, a campaign which has enjoyed the support of most Western populations. Depending on what metric you use to measure effectiveness, most would say that thus far the airstrikes have been a success. It is suggested that as many as 746 ISIS fighters have been killed by coalition airstrikes, of which even Canada has participated in, using her aged CF-18s to bomb ISIS positions around a dam in Iraq. By looking strictly at the numbers it would appear that thus far the campaign against ISIS has been a success. For my final blog post I will argue that while this may be the case, we must question the ramifications of these successes, and whether or not we are willing to continue indirectly supporting the regime of Bashar al-Assad.

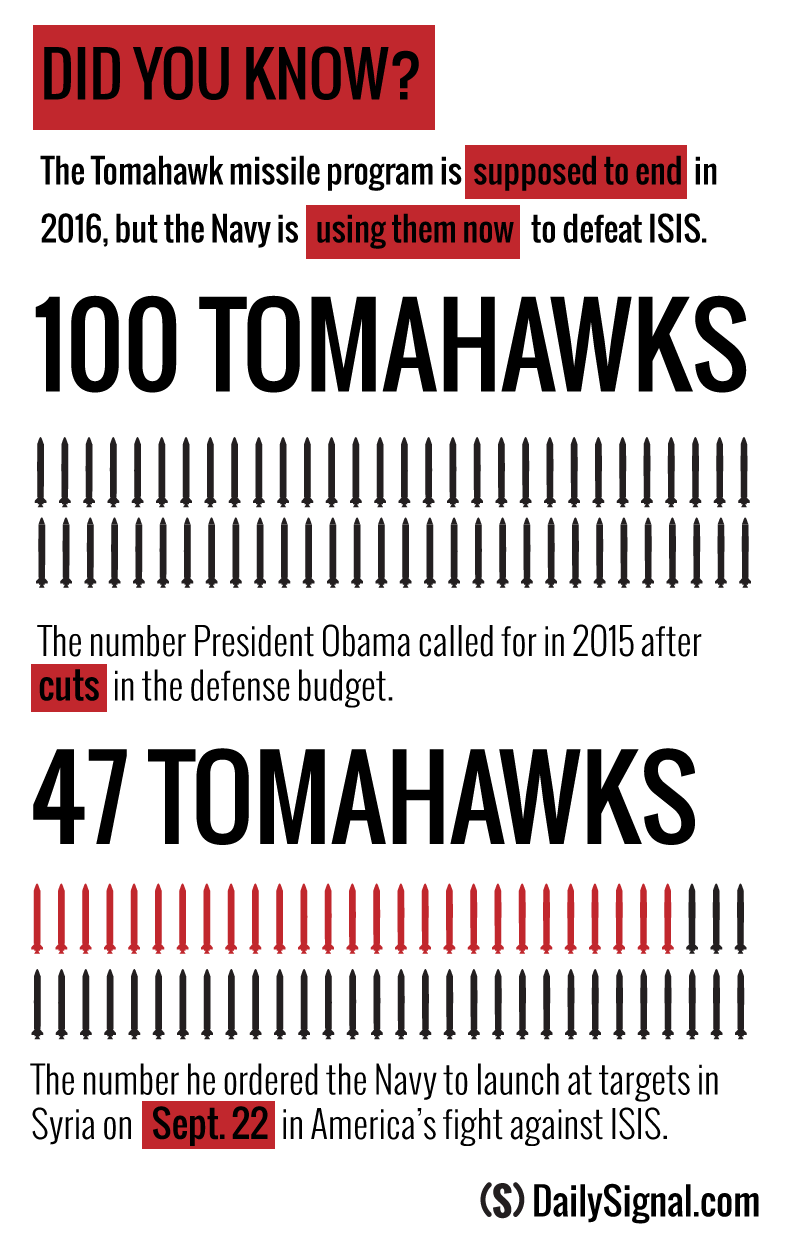

It was August of 2012 when President Barack Obama warned the Assad regime against using chemical weapons for fear of crossing a “red line,” a statement which has proven both misguided and an embarrassment to Obama’s foreign policy. After proof emerged that chemical weapons had been used, and the West concluded that these weapons had been deployed by the Assad regime, the wheels began turning for an international intervention against Assad, one which had previously been blocked by Russia in the UN Security Council. Unfortunately for Obama, the public support for a war against Assad was not there, and through an agreement with Russia to destroy all chemical weapon stockpiles, the Assad regime was saved from foreign intervention.

A year later, we are now bombing the single largest group of all the Syrian rebel factions, indirectly assisting Assad in retaking lands previously lost in what began as a democratic uprising in the Arab Spring. How did this happen? Is Assad not a bad guy after all? Or have we involved ourselves in a conflict in which there is no right side?

From the beginnings of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Bashar al-Assad made the strategic choice to focus his efforts in combating the more moderate rebels who had begun the revolution in the hopes of achieving a more democratic government. This included many of the various factions which constituted the Free Syrian Army. In doing so he created space for extremist groups such as ISIS to grow stronger and gain control of territory. In addition, the relatively little funding that the moderate groups received in comparison to the Islamist groups who received more funding by the Gulf States, the extremist factions were often better armed and better funded. Finally, their more extreme, religiously inspired ideologies drew more foreign fighters compared to those simply fighting for a more democratic future for Syria.

All these factors compound into a shift in the opposition over a three year period which saw the opposition become more heavily dominated by jihadist groups such as Jabhat al-Nusra, the various factions in the Islamic Front, Ahrar al-Sham, and of course, the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham. By allowing for this transition to occur, and actively encouraging it by targeting moderate groups, Assad effectively legitimized his role in the war as “a battle against terrorists,” which is how many pro-Assad supporters will describe the current Syrian civil war. In doing so he made himself appear less as a bad guy and more as a legitimate leader in the eyes of Western populations.

Then in late 2013 ISIS began making rapid gains seizing territory in Iraq, capturing major cities such as Mosul, Fallujah, and Ramadi. With the support of previously oppressed Sunni populations, they moved rapidly onwards towards the capital, Baghdad, capturing the attention of Western powers, particularly the US, who had only recently withdrawn from Iraq after occupying it for nearly a decade. Through the clever use of social media, ISIS spread propaganda in a manner which both attracted thousands of foreign followers while simultaneously appalling the rest of the world. In what was arguably one of their most clever uses of social media, they beheaded several Western journalists and aid workers, leading to massive public outcry and strong support for a military campaign against ISIS. This, coupled with their declaration of an “Islamic Caliphate” and their attempted genocide of the Yazidi people and other ethnic minorities, effectively set the stage for the intervention that both ISIS and Assad wanted. And this is exactly what they got.

It would seem then that ISIS is the greatest evil in the Middle East right now, begging the question – is Bashar really that bad? The simple answer is yes, he is. This is a man who has oppressed Sunni populations in Syria for decades, just like his father before him, an oppression which lead to the eventual revolution during the Arab Spring. What sparked the uprising, in fact, was the torture of 15 school aged boys for writing anti-regime graffiti. After the peaceful demonstrations began, the Assad regime brutally cracked down, opening fire on demonstrators in well documented massacres. Through photographic proof smuggled out of Syria by a state photographer, it has been shown that the Assad regime has committed “industrial-scale killings” of anti-regime protesters who had been detained, whose bodies bore evidence of widespread torture by various methods.

Warning: GRAPHIC

Throughout most of the Syrian civil war the Syrian Air Force has used indiscriminate barrel bombings in Sunni populated or rebel held neighbourhoods, killing thousands of innocent civilians. Human Rights Watch described the actions of the Syrian military as having “used ballistic missiles, rockets, artillery shells, cluster bombs, incendiary weapons, fuel-air explosives, barrel bombs, and regular aerial bombardment, as well as chemical weapons to indiscriminately attack populated areas in opposition-held territory and sometimes to target functioning bakeries, medical facilities, schools, and other civilian structures.” In 2013, a suburb of Damascus was struck by rockets containing the chemical agent sarin, killing hundreds of civilians and injuring thousands more. In the past month a video emerged showing the aftermath of a bombing (warning: GRAPHIC) which targeted a refugee center in Habeet Idlib, killing 65. These bombings and their effects are well documented as often times killing many more civilians than rebels, making them illegal under international law.

In addition, thousands of incidences of sexual violence against women have also been committed by Syrian security forces, both in detention centers and prisons, as well as in recaptured villages and cities. Throughout the Syrian civil war the Assad regime has committed numerous war crimes, and yet has largely not been held accountable.

Warning: GRAPHIC

More recently, there has been debate as to whether or not coalition airstrikes have directly aided the Assad regime in retaking ground previously lost to rebels. What is more certain is that many Syrians on the ground perceive this to be true, believing that the coalition has chosen to side with Assad. These views are not without just cause, as recently it was reported that the US actually provided the Assad regime with intelligence on jihadist positions. Interestingly the perceived collaboration between the coalition and the Assad regime has driven Syrians to consider joining ISIS, as they believe ISIS now holds their only hope for defeating the Assad regime. This includes Jabhat al-Nusra, previously known for their opposition to ISIS, who shortly after coalition strikes began, announced that they were considering amending relations with ISIS in the face of coalition attacks. Finally, due to the coalition’s involvement in combatting ISIS, more Syrian Air Force resources have been freed up, allowing them to focus more on cities such as Raqqa and Aleppo, leading to an increase in airstrikes which have led to reports of many civilian deaths.

So what is to be taken away from this blog post? I would like to make it clear that I am by no means arguing in favour of any of ISIS’ actions, nor am I suggesting that they are any less evil than they have been made out to be in the media. Rather, what I am suggesting is that as the Syrian civil war rages on, it is critical to be cognizant of the fact that there are no “right” sides in this war. If the trend of collaboration with the Assad regime continues, and as calls to even ally with him grow louder and louder, I would request that you, the reader, keep in mind who he is. Recall that he is a man whose regime has been complicit in widespread oppression, rape, torture, and execution. He is a man who uses indiscriminate barrel bombs and chemical weapons against his own population, as a means of punishment for rebelling against his rule. There is no justifiable application of “the lesser of two evils” argument when considering Assad and ISIS, because both are monumentally evil. It is for this reason that I described involvement in Syria as “a whole other can of worms” in my first blog post of the year, and it is why 4 months later, I stand firm in my beliefs that Western involvement in Iraq and Syria is both misguided and ill-advised.