It’s a familiar scene in classrooms and lecture halls across Canada. A teacher or professor keen to introduce a topic about Canada and its role in the world leads with the ever popular discussion question, “what values does the rest of the world associate with Canada?” Hands begin to go up, and classically Canadian ideals such as, “multiculturalism,” “acceptance,” and “igloos,” are suggested. More often than not, “peacekeeping” is also added in the mix. When this is suggested it elicits a patriotic response. Our heart swells imagining people around the world thinking fondly of Canada as the harbinger of peace, and lover of all things non-violent. They think of Canada, a country whose own Foreign Affairs Minister fathered the concept of peacekeeping. Canada, they imagine, a country who valiantly defends human rights in places of conflict worldwide. Canada, who specializes in apologies and just wants everyone to have a good time. In short, Canada the peacekeeper. Unfortunately this is no longer the case. Canada is no longer the peacekeeping force it once was, and for this we should be ashamed. Furthermore I argue that in face of these failures, Canada should revamp its efforts in peacekeeping and live up to our supposed reputation.

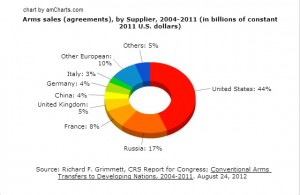

I’ll begin with a question. What do Rwanda, the DRC, and Congo have in common? Several things actually. All three are central African nations that have been ravaged by civil war. All three have GDPs that rank below $60 billion per year. All three have, at some point or other, hosted Canadian peacekeeping troops. And all three currently provide more troops to the UN peacekeeping force than Canada. Of the top ten contributors, six are African nations, with Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Nepal completing the group. In fact, Canada the peacekeeper doesn’t even break the top 50 contributors to UN peacekeeping forces. We rank 65th, amongst other such military and economic forces as Zambia, Tunisia, and Sierra Leone. Our contribution? 84 police officers, 13 military experts, and 21 soldiers as of September 2014. Still feeling proud of our peacekeeping reputation now?

There are several reasons for the decline of Canadian peacekeeping participation. The first is the incidences of failures the UN experienced in peacekeeping missions during the mid-90s. Between the Rwandan genocide in the presence of Canadian-lead UNAMIR forces in 1994, or the torture of a Somali teenager by Canadian troops in 1993, the ‘90s provided strong disincentive for future Canadian participation in UN endeavours.

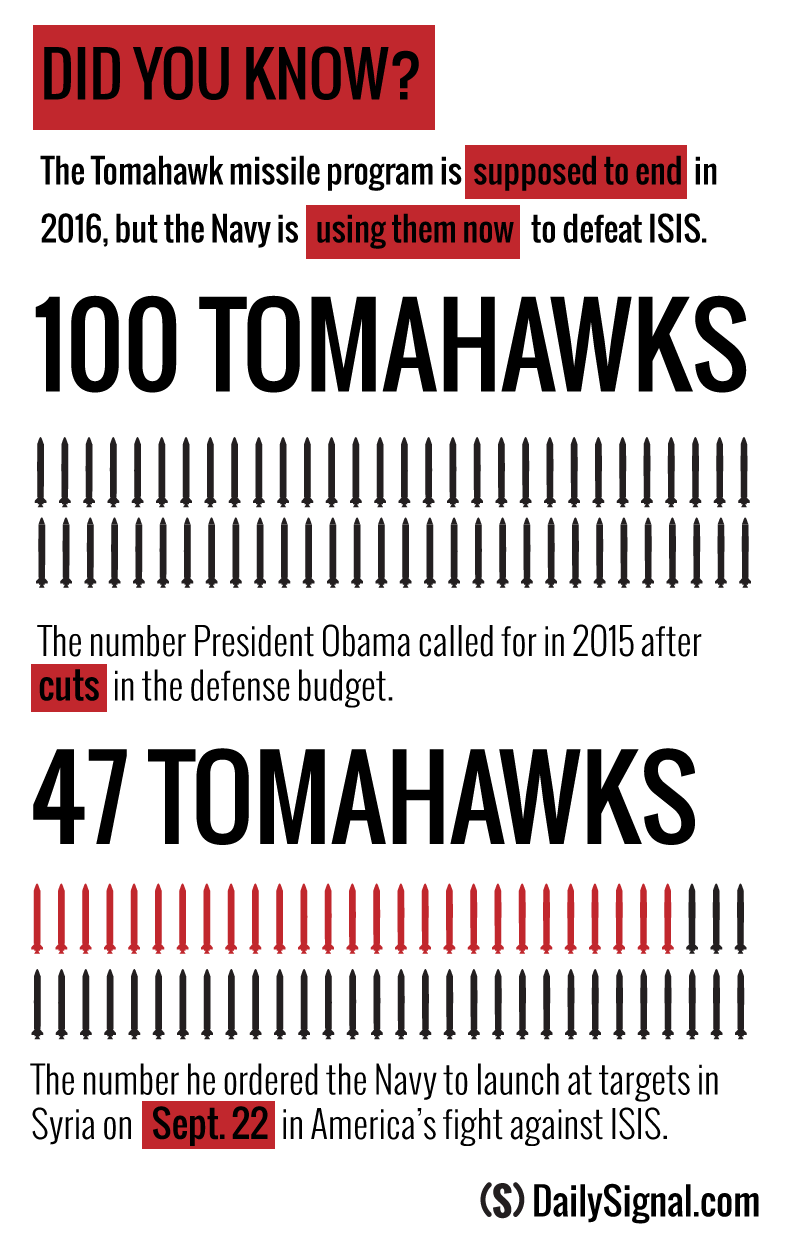

While this was happening, NATO began to rise to prominence as an instrument of humanitarian intervention, providing a second distracting factor. Since the 1990s Canada has chosen to participate more with NATO, fighting alongside the US and its allies in wars based on humanitarian intervention, a concept which it is important to note is fundamentally different than peacekeeping. Peacekeeping is dependent on the conflicted country’s consent, and uses lightly armed troops to enforce peace agreements, a practice which has been shown through statistics to decrease the likelihood of a return to violence. Humanitarian intervention, on the other hand, is based off of military supremacy and the enforcement of peace using things like no fly zones, precision airstrikes, and offensive counterinsurgency operations.

The effects of these NATO led interventions have been felt greatly in Canada. Earlier this year Canada finally finished returning her troops home from a decade-long war that one would be hard pressed to call a success. Thus the Afghanistan war is the third cause of the decline of Canadian participation in peacekeeping operations, as it consumed the majority of the Armed Forces’ resources and capacities. Due to the war Canada drastically scaled back its training and education for peacekeeping operations, and in 2013 closed the doors of the Pearson Center, a military training base intended to train foreign and Canadian military personnel in peacekeeping operations.

More recently decreases in peace support operation (PSO) training and contributions to UN Peacekeeping missions overall, can also be seen as a reflection of the Harper administration’s prioritization of missions that the US deems valuable, over those which the UN deems valuable. This can be seen recently in Libya, in which Canada assisted NATO in bombing runs meant to depose the Gaddafi regime, a mission which arguably destabilized the state and lead to the ongoing war today. If my predictions hold true, we should have the example of Syria and Iraq to point to in a few years as another botched humanitarian intervention for Canada to be ashamed of.

So what should Canada do? I have two possible solutions to this question. The first is that we make a concerted effort to revamp our peacekeeping traditions. At one time, 1 in 3 Canadian Armed Forces members wore a blue beret (UN peacekeeping outfit), a goal which I believe we should attempt to return to. We should reopen the Pearson Center, and expand its budget to better train our forces in peacekeeping and nation-building. We should realign our military interests with those which aim to preserve peace, as opposed to those which aim to make war. In doing this, Canada can return to its former role of being a leader in peacekeeping efforts, a role in which we can use institutions such as the Pearson Center and UN missions to spread our knowledge and peacekeeping ideals to other military forces worldwide.

It is interesting to note that in discussion, guest speaker Capt. Lisa Haveman noted that in Afghanistan, Canadian forces were more adept at nation-building endeavours than their American counterparts, a trend which bodes well for a Canadian return to peacekeeping practices. I don’t think it’s an unattainable goal for Canada, and her forces, to realign ourselves with more multilaterally supported peacekeeping missions, which are more likely to garner long term peace. Doing so would gain Canada greater prominence in the global security arena, and provide greater nation-building efforts to conflict-ridden states than bombs from a CF-18 ever could.

And the second option? The second option is one in which we maintain the status quo. We continue to train our military forces solely to make war, continue to bomb in the name of peace, and continue to follow Western interests into conflicts that are ill-advised. While I won’t judge anyone who prefers this option, I must insist that if we continue to go this route, we should stop patting ourselves on the back for peace we do not keep.

In my eyes, this is what Canadian peacekeeping in the 21st century comes down to. We can return to the values that Pearson instilled in us, values that we pride ourselves on and enjoy presenting to the world. Or we can carry on with the realist attitude that all wars can be solved with bombs, and that all soldiers should be warriors, and in doing so forget our past peaceful ideals. Personally, I prefer the former.